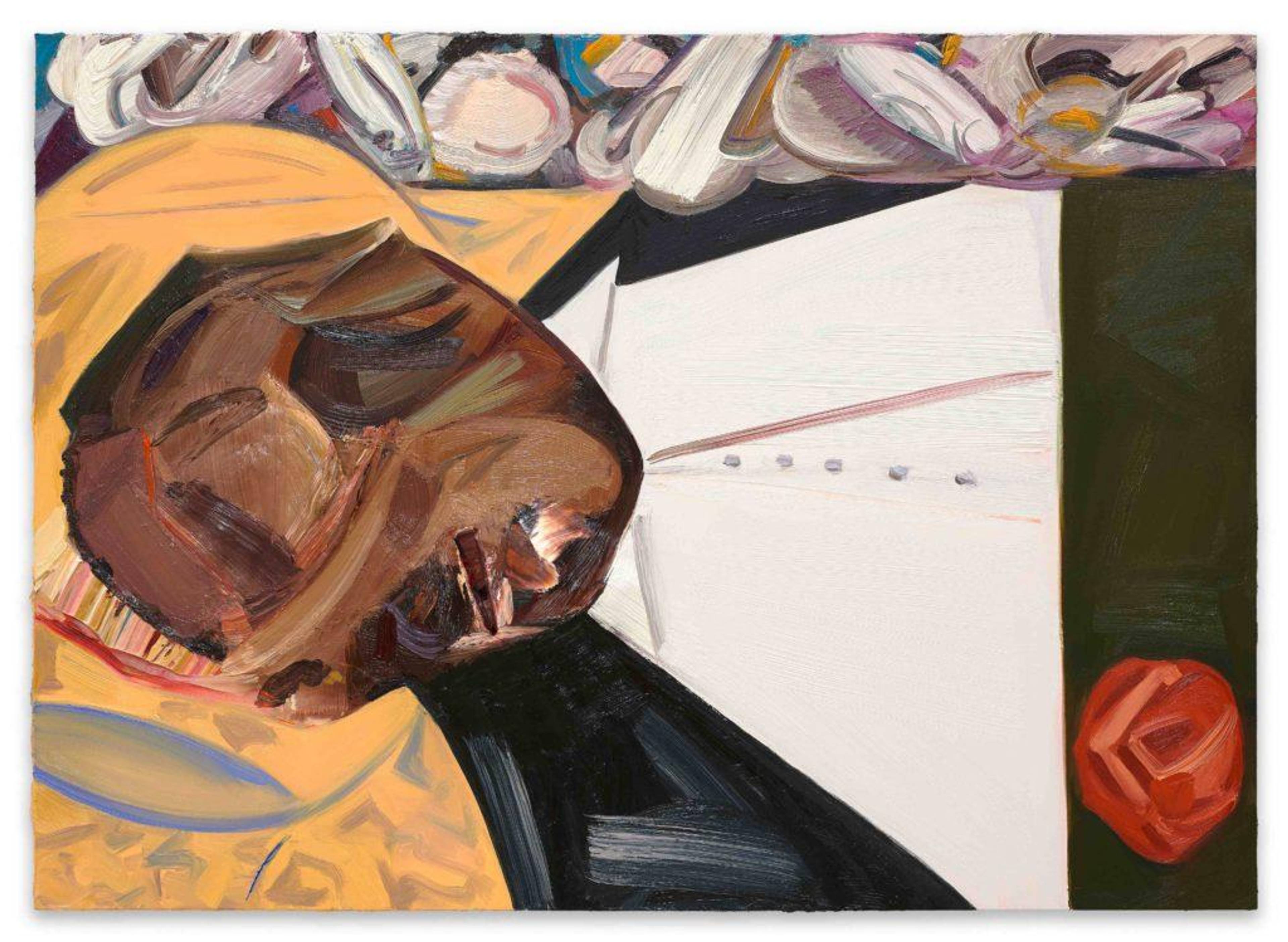

A painting by Dana Schutz included in this year’s Whitney Biennial in New York has been criticized for perceived racial insensitivity. The painting depicts the mutilated face of Emmet Till, a 14-year old boy brutally murdered in 1955 after it was falsely claimed he flirted with a white woman. The artists Hannah Black and Parker Bright as well as the artist and curator Aria Dean and “many in the black art community are upset by the work” (P. Bright) and have voiced their criticism.

The debate is a symptom of a growing malaise in the current art world. It points towards more general issues surrounding “political curating” that should not be obscured by a highly polarized quarrel around ownership of subject matter and group membership.

A letter by the artist Hannah Black penned and signed, as Aria Dean insists on facebook [all links are provided at the end of this article], “with the support of countless artists, writers, friends, etc. many of whom would collectively like to make very clear that the letter was a concrete call to dispose of Schutz’ painting”, is at the center of the debate. It provides arguments in support of a series of claims which seem to be shared by large parts of the art world:

“It is not acceptable for a white person to transmute Black suffering into profit and fun, though the practice has been normalized for a long time.”

The formulation dresses this up as a claim that can hardly be contested. Transmuting suffering into profit and fun is never acceptable. But the formulation is misleading. The allegation that the painting only exists “for profit and fun” is not grounded in any argument and the double reduction happening here is too exclusive: the work is reduced to one of its topics (“Black suffering”) and its maker to one of her group memberships (“a white person”). The argument ignores other topics and group memberships which might have rendered Schutz’s painting acceptable even within the restrictive representational regime that the signers subscribe to. In the following paragraph, group membership is used as a foundation for ownership :

“The subject matter is not Schutz’s; white free speech and white creative freedom have been founded on the constraint of others, and are not natural rights. The painting must go.”

The idea of ownership of certain topics, experiences or events is essential to the argument. The signers of the letter claim exclusive Black ownership of Black suffering which comes with exclusive representational rights. This should be granted by white people, they argue, as a gesture of reparation and good-will. There is a strange reminiscence of copyright law or intellectual property here, which seems quite inappropriate to me, but there is something even more worrying about the argument. While possibly rooted in pain, such a claim is both politically and ethically problematic. If accepted, its consequences would be devastating. It would lead to representation monopolies where Muslim media wouldn’t be allowed to cover the death of Christians, only Palestinians could speak about Israeli attacks, the Armenian Holocaust could only be treated by Armenians, etc. The consequence of this would be representational segregation, where only one group’s perspective on a kind of event would be visible and all other perspectives considered “fake”. In such a regime, even sharing one’s human concern for the suffering of humans of another group would be considered illegitimate.

Understanding that the argument brought against her was based on the artist’s social and racial status as a white person rather than the actual painting, Schutz herself tried to legitimize that she painted a work about the brutal killing of a young boy by referring back to her personal identity not as a white person but as a mother:

“I don’t know what it is like to be black in America, but I do know what it is like to be a mother. Emmett was Mamie Till’s only son. The thought of anything happening to your child is beyond comprehension”.

Schutz thus tries to defend her right to representing the dead Emmet Till by claiming that another group/topic pair is relevant to the painting. She tries to replace the pair white person/Black suffering considered incompatible with the pair mother/death of a child , thereby claiming the irrelevance of race for the topic. By accepting that she cannot “own” the suffering of a black boy or a black woman, but claiming ownership of the suffering of a mother, she accepts that ownership of subject-matter and group membership really are central to her painting’s legitimacy. Rather than rejecting the idea of representational segregation, Schutz singles out her undeniable membership in a group which, she claims, gives her the right to create new representations of the topic. But the appropriateness of her group membership can again be denied considering that her child couldn’t probably die in a racist attack. Aria Dean has done so:

“My feeling as someone with even the vaguest potentiality of black motherhood (and furthermore black parents in general, fuck the invocation of motherhood to some degree, black fatherhood is plagued with these same worries) that the degree to which the murder of your child is incomprehensible to a white mother exists on a plane very distant from the way that possibility exists in the mind of a black mother. [...] To equate white motherhood, black motherhood and the fear that runs through each of them is violent and nothing else.”

It is true that there are different degrees to which the fear that one’s child could die can be justified. But the fundamental gesture made by Dean here is to deny a person’s right to be emotionally affected by an event because she is not part of the right group. This is disturbing. The monopoly of representation is here paired with a monopoly of grief over certain events. This seems as absurd as it is brutal. It also leads to a situation where such denials could go on indefinitely. Even Dean’s own ownership of the topic could be denied. To do so would seem absolutely absurd to me, but the possibility is part of the ownership logics: After all, Dean did not grown up in the America of the forties or fifties and for people who did, it might be offensive that she equates her current situation in America with that of Black Americans in the fifties. To defend herself, she could then only refer back to her emotional involvement with the event, which is, however, unverifiable beyond her claim and could therefore be denied.

All this shows how problematic it is, in practice, to single out a unique group for a person or a subject and how absurd and painful discussions based on the idea that certain groups own certain subjects are bound to become. I believe that they should be abandoned altogether.

More generally speaking, the allegations of the signers of Black’s letter, as well as Schutz’s defense, are highly problematic insofar as they are based on the kind of Essentialism that also characterizes white suprematism: everything important we need to know about Schutz’s painting is that there is a conflict between the the artist’s whitenesss and the Blackness of the painting’s subject. This reproduces a kind of thinking which has to be overcome for deep change to take place.

This brings us to the heart of the matter: The reason for denying Schutz (and the curators of the show) any ownership of or deep preoccupation with the matter at hand is the allegation that Non-Black-people prefer to only pretend to act up against anti-Black-sentiment rather than really doing so:

“The evidence of their [Non-Black-people’s] collective lack of understanding is that Black people go on dying at the hands of white supremacists, that Black communities go on living in desperate poverty not far from the museum where this valuable painting hangs, that Black children are still denied childhood.” (from Black’s letter)

Dean makes a similar point when she responds to the curators’ claim that exhibiting the painting is a political gesture in an “especially divisive time”:

“We’re again confronted with this ongoing and tiresome problem, where white and non-black people make symbolic gestures toward their supposed dedication to curbing antiblackness and overtly anti-black violence and refuse to do any work that has material impact on the lives of actual black people in this country.”

If you really care, you help to transform America through direct action rather than putting seemingly political paintings on exhibition walls, which provides a purely symbolic outlet. Dean’s remark points towards the current hype around “being political” as a sine qua non for art-shows, festivals and Biennials, where political artmaking and curating are often substitute gratification in place of real political action. The controversy around Dana Schutz’s painting is merely a symptom of a malaise in the current art world, where “being political” is considered a must and is often claimed without signs of deep involvement, an attitude which Black and Dean find Schutz and the curators of the Biennial guilty of.

Finally, let us look at the painting and try to understand if there is anything offensive in the way it treats its topic. I believe there is.

The work’s title reflects the decision of 14-year-old Emmet Till’s mother to leave the casket of her boy open, saying, “Let the people see what I’ve seen”, the results of a brutal racially motivated mutilation. Within this context, the very painterly brushstrokes used by Schutz to depict Emmet Till’s face might be interpreted as a reflection of the violence of the mutilation, especially as they are in sharp contrast with the more delicate brushwork used for the white shirt. The red rose on the right of the painting may appear like a sign of resistance and dignity, with one of the brushstrokes even looking like a raised fist.

But a more critical interpretation of the work reveals its profound ambivalence. The violent painterly treatment of Emmet Till’s face makes it impossible to tell what is just a painterly effect and what is part of the depiction of the young boy’s disfigured face (which we know from photographs). The painting thus physically obscures the actual mutilation as it took place. Rather than extending the reach of Mamie Till’s brave decision by giving the mutilation more visibility, the painting may actually be seen to counteract her decision of letting the world see the brutality of racial hatred that went unpunished. Blurring the face in what may well be an act of unconscious painterly censorship, Schutz virtually closes the casket that was supposed to remain open.

Seen from the perspective of the act of painting rather than its result, the violent painterly treatment is also ambivalent insofar as it may appear to virtually repeat the act of mutilation of the boy’s face rather than questioning the violence of this act.

Last but not least, painterly brushwork draws attention to the painter rather than the subject. Modernism made it the supreme sign of painterly virtuosity, instances of which are celebrated in Rembrandt or Titian. Making visible the artist’s hand, such brushwork is also regularly perceived as a sign of self-expression and self-affirmation. This creates an unfortunate tension with the topic of Schutz’s work. The work, it may be said, is too much about her as a painter and too little about Emmet, let alone the suffering of his mother.

All these elements seem to make the painting too ambivalent to be called a great work of art. They may also have contributed to the disturbing effect the work had on Bright, Black and others. The artist’s “manner” should thus be a more important issue in the debate – and certainly more so than her whiteness. Apparently, both the artist herself and the curators lacked the perspicuity to perceive these problems when they included the work in the show.

While many things got mixed up in this debate, there is still something we can take away from it, once we strip the controversy from its preoccupation with subject ownership and Essentialist arguments: the beginning of a conversation about supposedly “political curating” and “political art” as providing substitute gratification for its practitioners rather than contributing to real political change.

N. B. While I am a "white or white-affiliated critic" and am thus a member of a group which the signers of the letter deeply mistrust and come close to preventively disqualifying altogether, I hope that it is understood that my aim here is not to "deride discussions of appropriation and representation as trivial and naive" as anticipated in the letter, but rather to take them as seriously as possible. I will however always speak up against preventive or reactive disqualifications of out-group voices. They obstruct constructive exchange across different groups and can eventually make group members immune to healthy criticism from "outsiders". The devastating consequences of this are apparent throughout history, not only in Germany, my own country of origin, but also in so many other places of the world. Preventive discrediting of the opinions of out-groups is a propaganda technique used by totalitarian regimes and fundamentalists. I believe that we should not even come close to using it ourselves.

References and Further Reading:

The basics are in The Guardian . Black’s letter is in Artnet News . Schutz’s initial reaction was quoted in the Guardian article. Aria Dean’s reaction is on her facebook profile. A more complete reply can be found in an interview by Artnet News .The importance of Mamie Till’s decision and the initial photographs for the Black Civil Rights Movement have been reconstructed as part of Time’s 100 photos video series . The historical facts have been narrated in an article in New Republic , where I also discovered an analysis of the painting which is quite similar to mine.

Klaus Speidel is an image theorist, art critic and curator, currently based in Vienna.