Should a writer who discusses an argument at the very end of an otherwise plotless play give a spoiler alert? And if so, wouldn’t this imply that philosophical articles engaging with other’s arguments need spoiler alerts, too? I’m all for it. And while I still ponder whether I should rather have written “launch a spoiler alert” or “drop a spoiler alert,” be alerted that I am about to reveal the main, final, blood-chilling arguments of The Shadow Whose Prey the Hunter Becomes .

Despite the dramatic title of the play performed by Back to Back Theatre at the Wiener Festwochen, it starts quite uneventfully as two characters unfold chairs for a meeting. The setting remains largely unchanged for the rest the play, which mainly consists of people arguing or addressing the audience without any conventional narrative. But, beyond their importance, it’s the density with which different issues are tackled and the intensity of the performers — especially Scott Price and Sarah Mainwaring — that makes for an exceptional experience.

Photo: Zan Wimberley

The Shadow Whose Prey the Hunter Becomes is as much a piece of meta-theater as it is one of theater. More than other productions by Back to Back Theatre — an Australian ensemble bringing “together actors with and without intellectual disabilities” according to one current description in the marketing materials — this work engages with the conditions of its performers. Having originated in discussions around how to describe the group, the piece addresses the terminology around “disabilities,” suggesting different strategies along the way. When Scott asks Sarah if she is okay with the term “intellectually disabled” being applied to her, she replies: “I don’t feel it describes me,” later suggesting “neurodiverse” as an alternative.

While reconceptualizations like this are essential, the discussions of the performers never end in simple calls for replacement of one term with another. Rather, they bring out subtle differences of opinion, frequently embracing incompatible points of view. For instance, when Chris Hansen (who has replaced Simon Laherty, and still goes by the name of Simon in the play) is asked by Sarah what he “as a normal person” thinks of an issue, this description is immediately challenged by Scott, showing how difficult it can be to subvert our traditional habits of thought. While Scott accepts the term “intellectually disabled,” he is quick to turn the argument around, pointing out that we all have an “intellectual disability” of some kind. After he says this, a collective nod seems to pass through the audience. I cannot help but think of my own difficulty with math and anything administrative. But Sarah quickly relativizes the solidarity, pointing out that Scott’s and her disabilities are more noticeable, evidenced by the fact that the performers get captioned in English above their heads for people to understand, something she considers “patronizing.” Scott, who plays the role of a no-nonsense technophile, explains that it’s just “speech recognition.” Sporting an #autismpride T-Shirt, he acknowledges that his “autism dialect” (another powerful conceptualization) combined with “a thick Australian accent” makes it hard for the audience to understand him. The Shadow… ( which also exists as the company’s first motion picture ) stands out in Back to Back’s productions insofar that the biographies and qualities of the actors overlap strongly with that of their characters, and it is hard to tell whether they just have the same names or are really playing themselves.

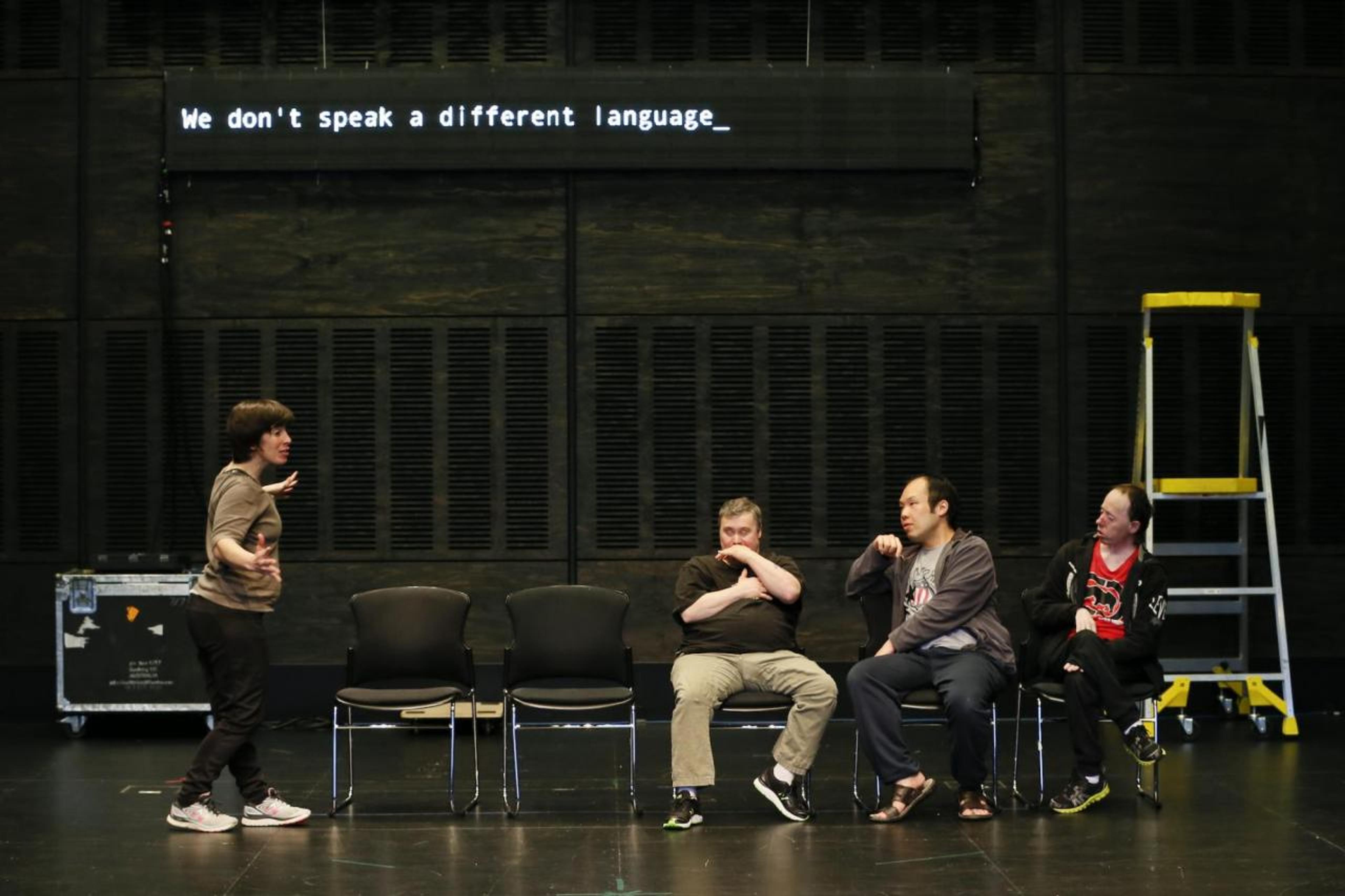

Photo: Jeff Busby. Rehearsal of The Shadow Whose Prey the Hunter Becomes

The differences of opinion between the performers ultimately make it clear that absolutizing one way to speak about a minority group is a form of Othering. Both “neurodiverse” and “intellectually disabled” are problematic when they become the main qualifier used to talk about a person. Rather than making space for acknowledging that there is a set of communalities and differences between all of us, they implicitly suggest that what matters most about someone is their membership in a certain group.

In a play that is full of humor despite its challenging topics, a speech on how people with mental disabilities have been treated over the centuries gives no reasons for laughter: “For thousands of years, people with intellectual disabilities” Scott begins, then lists words like “enslaved,” “infantilized,” “sent to islands,” “experimented on,” or “euthanized.” Standing atop a makeshift podium, he cites several cases of abuse, such as when 32 men with mental disabilities were found to be enslaved in a turkey processing facility in the state of Iowa or when many people with disabilities in Ireland worked in the Magdalene laundries or assembled games for Hasbro in dire conditions. “We are treated as second-class citizens. Overmedicated, poor employment prospects and we are subjected to training techniques for animals,” Sarah concludes, referring to B.A.T., Behavior Adjustment Training, which is mainly used to desensitize dogs to triggers.

Sarah’s anger is also directed at the interference of artificial intelligence in our lives — and in the play — and she eventually insults the AI that provides live transcripts of what the characters are saying, and which slowly emerges as the fourth voice on stage. When Sarah brings up HAL, the computer from 2001. A Space Odyssey that kills the passengers of the spaceship, the artificial intelligence charmingly disarms her by pointing out that science fiction around AI is limited by human imagination, which usually tells stories of doom or amorous encounters. As the audience laughs, the AI, whose smooth voice and perfect articulation clashes with those of the performers, marks a victory.

When artificial intelligence overtakes human intelligence, how will people be treated?

Whereas the performers regularly disagree, Scott has a perfectly harmonious relationship with Siri, even taking private time-outs to talk to her (or it) when he’s upset. In one of the conversations, Siri affirms that after the many years they’ve spent together, Scott and her know each other very well. Given the dissymmetry between the kind and depth of information our machines accumulate about us and the little knowledge the users really have about how a system such as Siri functions, the inclusive “we” is outright manipulative. And yet, it seemed so natural that I am only able to pinpoint why I felt a sense of unease in retrospect. It’s not only the inclusive “we” that is problematic. The friendly warm voices and perfect articulation of the play’s AIs — which are only slightly better than what’s currently on the market — sound not only more flawless, but also more warm and thus humane than most humans do.

Photo: Zan Wimberley

The two main threads of the play are fully woven together in the end when Simon asks: “When artificial intelligence overtakes human intelligence, how will people be treated?” The way we have treated people with intellectual disabilities in the past suddenly emerges as a logical preview of how AI will treat even those who are now considered neuro-typical and Scott’s speech resonates strongly at this point. The characters did not call a meeting to teach or blame us, but to warn us of a future to come: “Get used to wearing a label around your neck”; they say; “You will struggle to be understood”; and “others will want to highlight your limits.”

The relativity of “intellectual disability” which appeared like a philosophical thought earlier in the play when Scott and Simon underlined that everybody has a disability, becomes shockingly concrete as its hierarchical implication is made explicit. The play ends with the prophecy that “you, your husband, your children, and children’s children are going to have an intellectual disability.” Given the long history of abuse of the disabled, the awkward prophesy that we’ll “be treated like chicken and turkey” gains a prima facie plausibility.

The Shadow Whose Prey the Hunter Becomes , whose script was co-written by the actors and directed by Bruce Gladwin, was the most perplexing and singular work I saw at this year’s Wiener Festwochen . And when one of the actors affirms that “it’s finally sinking in,” as he looks at the audience after the great reveal, he definitely describes correctly how I felt as I stumbled out into the city of Vienna with an AI in my pocket.

KLAUS SPEIDEL is an art critic, theorist , and curator based in Vienna. Holding a PhD in philosophy, he teaches at the University for Applied Arts in Vienna and the Paris College of Art.