The predictable formula for survey shows follows this logic: Chapter 1 (10% of the show), “They were struggling to find their voice, doing what other people did at the time”; Chapter 2 to 8 (80% of the show), “Then they started producing the same thing over and over again, getting better from year to year”; Chapter 9 (10% of the show), “When they were old, they were still very good at doing the same thing”. In contrast to this formula, the Austrian artist Josef Bauer, who’s now 86 and has been making art for 70 years, keeps reinventing himself – exploring new questions, ideas, and media with each series – without the kind of obsessive self-imitation we call “signature style”. In the retrospective at the LENTOS Kunstmuseum in Linz, Bauer’s hometown, we discover a conceptualist who still has fresh ideas. Taking in Bauer’s work now creates the impression that he not only beat many of his fellow Austrians to the punch, like Franz West or Erwin Wurm, anticipated by Bauer’s tactile poetry beginning in the mid-1960s, but also independently explored similar strategies to those of his American contemporaries. While there is some justification for being obsessed with precedence when ideas are the generative force of art – in conceptualism especially – the Viennese writer Karl Kraus said it best: “There are forerunners of originals. The owner of a thought is not he who had it first, but he who has it better”.

Installation view “Josef Bauer. Demonstration”, Photo: maschekS

In Bauer’s Gedeck für eine Person (Cover for one person), 1969, we find a spoon set on a table that sits beside a photograph of a fork and a print with the German word for knife, Messer . In the middle, there is a stone playing the role of a loaf of bread. Rather than just making a dry conceptual point, Bauer stages what he calls a “situation”: an absurdist narrative scene of the kind that could also appear in a Charly Chaplin movie (think of Chaplin eating his shoe soles like a steak and his shoelaces like spaghetti in The Gold Rush , 1926). Bauer’s scene begins to play out in our head when we imagine sitting down and trying to eat the stone bread with the photograph of a fork in one hand and the word “KNIFE” in the other. Conceptually, this work brings home the same points about representation with objects, photographs, and words as Joseph Kosuth’s One and Three Chairs (1965), with a chair, a photo of a chair, and a painting featuring a dictionary definition of “chair”. As opposed to Kosuth’s, Bauer’s work engages our imagination and not just our intelligence, which makes it more relatable, funnier, and ultimately more efficient as a Witz (joke).

Bauer kept an ordinary day job at the Finance Department of the Chamber of Agriculture in Linz, producing art at night in his spare time. His daily exposure to the materials of administration – endless streams of photocopies and DIN standards – may well have immunized Bauer to the allure of the bureaucratic aesthetic that defined much of the concept-driven work of his contemporaries. Whatever the reason, the result was that, unlike his fellow conceptualists, Bauer never fell for the illusion of neutral forms, which turned conceptual art into something so tedious that even one of its least boring representatives, John Baldessari, felt compelled in 1971 to promise I Will Not Make Any More Boring Art .

Zweifarbenbild gelb , 2019, Courtesy Josef Bauer; Krobath, Wien; Galerie Karin Guenther, Hamburg

Bauer’s Verfügbare Pinselstriche (Available Brushstrokes) – a series of works begun in the 80s – are deft tongue-in-cheek criticism. What at first sight appears to be a collection of colourful brushstrokes applied to black-and-white photographs, turns out to be reproducible plaster sculptures that can be applied anywhere. Their titular “availability” is conveyed through a box full of these “brushstrokes”, seemingly there for the taking. Straddling the line between sculpture and painting, the work is a playful commentary on the commodification of expression.

As much as Bauer resisted formal rigorism, he also refrained from the conceptual vocabulary now so prevalent in art schools. In works like Farbenbild (Colour Picture, 1985), the artist printed the word Gelb (yellow) in a blue monochromatic painting. Exploring this idea further, he made Zwei Farben Bilder (Two-Colour Pictures, 2003). The title becomes meaningful in its own right as the paintings actually have three colours, though only two are visible, while the third is identified by a word, written in another colour. Through these paradoxes, Bauer makes language slippery, something unreliable, made of interchangeable parts.

So, why didn’t this generate a market success? First, to create a market, you need to offer a pastiche of yourself, with such regularity as to become identifiable as an artist and a brand. Second, he was never represented by a big gallery. During much of his lifetime, he didn’t even have a gallery at all, so some of his major installations rusted in his garden after having been exhibited. Third, he stubbornly chose to live his life in the periphery, Linz, rather than in an artworld capital. Fourth, he was undogmatic at a time and in a space where dogmatism in art was perceived as the hallmark of seriousness. Fifth, he is funny and thereby became a protagonist of “the repressed history of conceptual art”, as Heather Diack calls the lighter side of conceptualism. Sixth, he made art in German, with many of his most significant works – including those cited here – needing translation, robbing them of much of their effect and immediate appeal for an international audience.This points to a general problem with artists who work with words and thus rely on their audiences understanding a certain language to immediately get the wordplay at stake. It might less be Bauer’s Austrianness that stands in the way of a wider reception than the inherent limitations of works in a certain language. We can easily overlook the linguistic dominance of English in conceptualism, but doing so may blind us to the subtleties and impact of Bauer’s work. This would be a shame.

Klaus Speidel

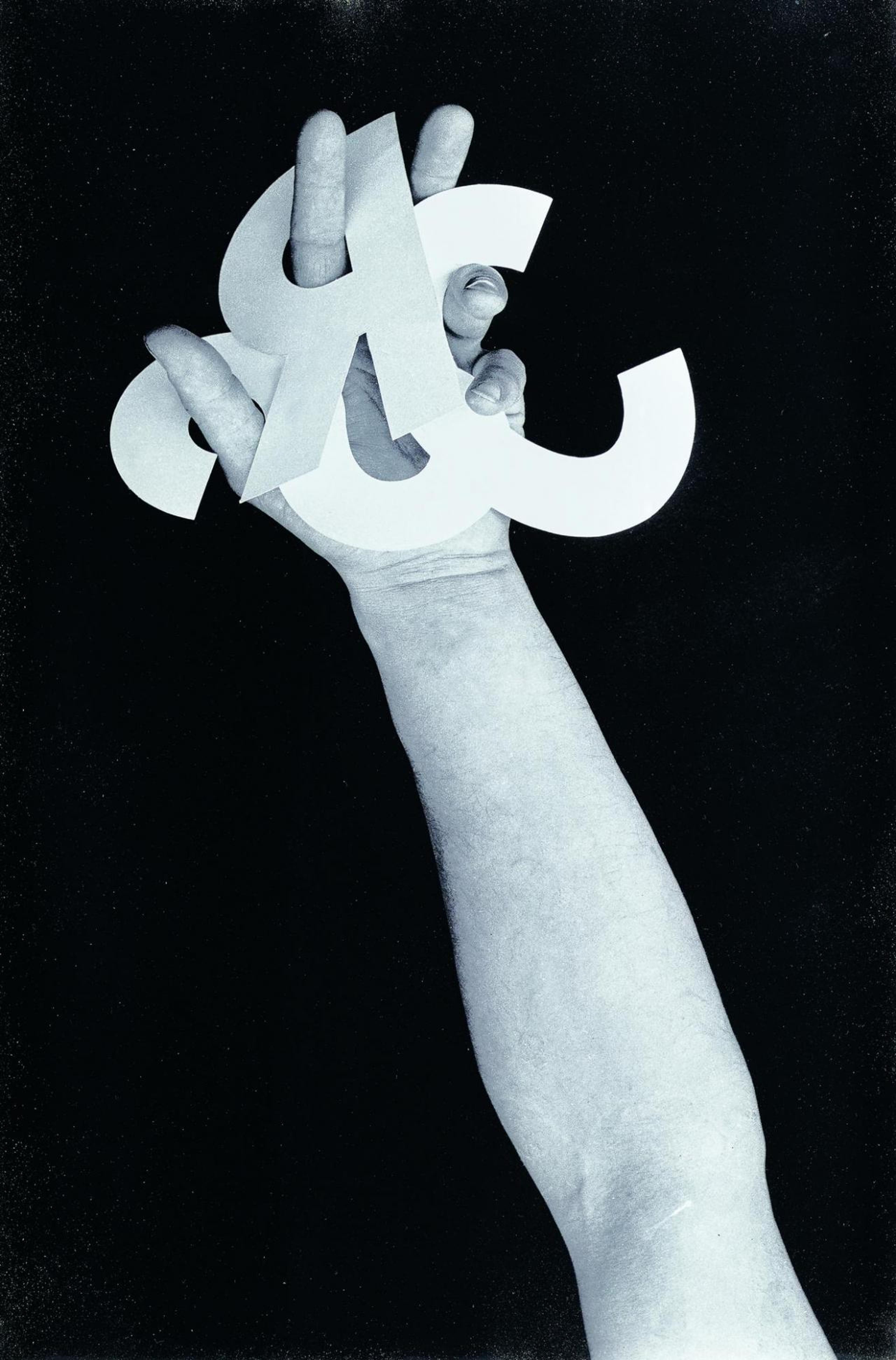

Taktile Poesie , Handalphabet , 1969, Photo: © Belvedere, Wien, Johannes Stoll Courtesy Josef Bauer; Krobath, Wien; Galerie Karin Guenther, Hamburg

"Josef Bauer. Demonstration”

LENTOS Kunstmuseum Linz

2 June – 4 October 2020