It was Sunday afternoon, at the end of the long fair week, when I discovered a fictitious mattress store in the “Unlimited” exhibition hall at Art Basel. In front of the entrance to Guillaume Bijl’s Matrazentraum (Mattresses Dream, 2003–23), a display advertised: “The best mattress free to your door.” How wonderful: The whole promised a gentle touch-down. I was ready. Inside the tube-shaped room, several stacks of mattresses shrink-wrapped in plastic foil awaited their imaginary buyers, creating a very convincing, detail-obsessed counter-fiction to the larger trade-show backdrop. Just around the corner, the performance Ménage de la maison (House Cleaning, 2022), for which Olaf Nicolai had hired the German actors Meike Droste and Thomas Rudnick to put on a daily cleaning performance in the fair hall, was similarly spot on. Maybe I’m wrong, but during the Tuesday afternoon opening, it seemed to me that Droste, dressed as a service worker, was scantly noticed by the audience. Quite a few people simply overlooked the actress, despite her eye-catching orange coat and the motions of scrubbing and sweeping in their midst. Was this social behavior learned, or simply due to the many other attention-seeking works of art on the premises? Actually, there was some not very persuasive art here after all, such as Gerhard Richter’s uninspired, three-meter-high digital print STRIP-TOWER (2023). Elsewhere, several XXL-format paintings (by Martha Jungwirth, Thomas Scheibitz, Conny Maier, Katherine Bradford, Günther Förg, and Yu Hong) seemed to be engaged chiefly in a silent competition for square meterage.

Next door, at the main event, orientation was as difficult as usual, in view of its sheer mass. Among the outstanding contributions was undoubtedly Tolia Astakhishvili’s Simple judgments and polite answers (2023), which brought a desolate and sensitive mood to the fair. Represented by the Tbilisi gallery LC Queisser, Astakhishvili is having a moment, with acclaimed, ongoing exhibitions at the Bonner Kunstverein and the Haus am Waldsee in Berlin. I also lingered in front of two handfuls of paintings from the series “Traffic Signs for the Hearing Impaired” (1990) at P.P.O.W., produced by Martin Wong in New York in the early 90s during his six-month residency at the New York City Department of Transportation’s sign shop. Here, the artist, who worked with various language and sign systems throughout his career, married the designs of common traffic signage to hand gestures from American Sign Language. Finally, at the booth of the Munich gallerist Deborah Schamoni, I was captivated by the dark, turquoise-green glow of a hinged image sculpture by Yong Xiang Li, born in 1991. a break (by the bamboo wave) (2022) seemed to hover between architecture and interiors, two- and three-dimensionality, culture and nature, history and the future. An entirely contemporary condition.

Guillaume Bijl, Matratzentraum, 2003–23, mixed media installation, 4 x 6.25 x 13.75 m. Courtesy: the artist and Galerie Nagel Draxler

Yong Xiang Li, a break (by the bamboo wave), 2022, acrylic, sand, and varnish on gessoed wood panel, stainless steel hinge, 205 x 150 x 45 cm. Courtesy: the artist and Deborah Schamoni

Even if quite a few art-world players have returned to their pre-pandemic flying routines, the climate crisis and its impact on the present and future, as well as the turn toward sustainability, were major themes in many of this year’s exhibition formats. This was perhaps most tangible at Liste Art Fair’s Hall 1.1, traditionally the most important platform for recent positions in international contemporary art, where the exhibition insert “Whistlers,” organized by the Munich-based curator Sarah Johanna Theurer, dealt directly with these themes on the so-called piazza at the fair’s architectural center. Styled like a documentary film, the thirty-five-minute video Making of Earths (2021), produced by Geocinema (Solveig Qu Suess & Asia Bazdyrieva), approaches the geopolitical dimension of weather and climate research in China and Southeast Asia, including footage from a Chinese Belt and Road Summit on the development of new trade routes and the durational collection of climate data. In the entrance area, in musician and sound artist Tomoko Sauvage’s installation In Curved Water (2010), nearly a dozen chunks of ice hung from the ceiling via ropes, their slow melt-off dripping into white bowls, which were miked and amplified to produce a minimalist soundscape. Time is running out.

In contrast, considerably more material and personnel were deployed for the Monday evening performance of Andrea Büttner’s Piano Destructions (2014/2023) in the basement of the Kunstmuseum Basel, just across the river. Roughly speaking, Piano Destructions consisted of two parts. First, the audience was shown various historical performances on four wall-sized video projections, in which pianos were battered with water, stones, and various tools. For example, there were scenes of a November 1994 performance by Nam June Paik in New York commemorating the Fluxus artist Charlotte Moorman, who passed away in 1991. During the performance, the legs of a piano played by Paik were sawed off and its innards smashed. Another piano was theatrically knocked over several times to squash raw eggs, tomatoes, bananas, and – symbolically – the artist himself, who was visibly having fun in his role as a “mad scientist.” In the second part of Büttner’s performance, nine female pianists entered the room to play music on as many pianos by Robert Schuman, Fanny Hensel, Frédéric Chopin, and Claudio Monteverdi. The piece, according to Büttner, “is about making art history in an artistic form,” offering a critical perspective on the male-connotated berserkism of the avant-garde. But of all things, is virtuosic Neo-Romanticism a suitable or adequate counterpoint? Or is the performance about the hopelessness of bourgeois cultural tradition and avant-garde ideology in equal measure? As is often the case with Büttner, doubt and the act of questioning appear as central elements.

Tomoko Sauvage, In Curved Water, 2010, ice, porcelain bowls, water, ropes, hydrophones, sound system, dimensions variable. Courtesy: the artist

Andrea Büttner, Piano Destructions, 2014, performance, Walter Phillips Gallery, Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity, Canada. © Andrea Büttner / ProLitteris. Courtesy: the artist and Walter Phillips Gallery, Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity. Photo: Rita Taylor.

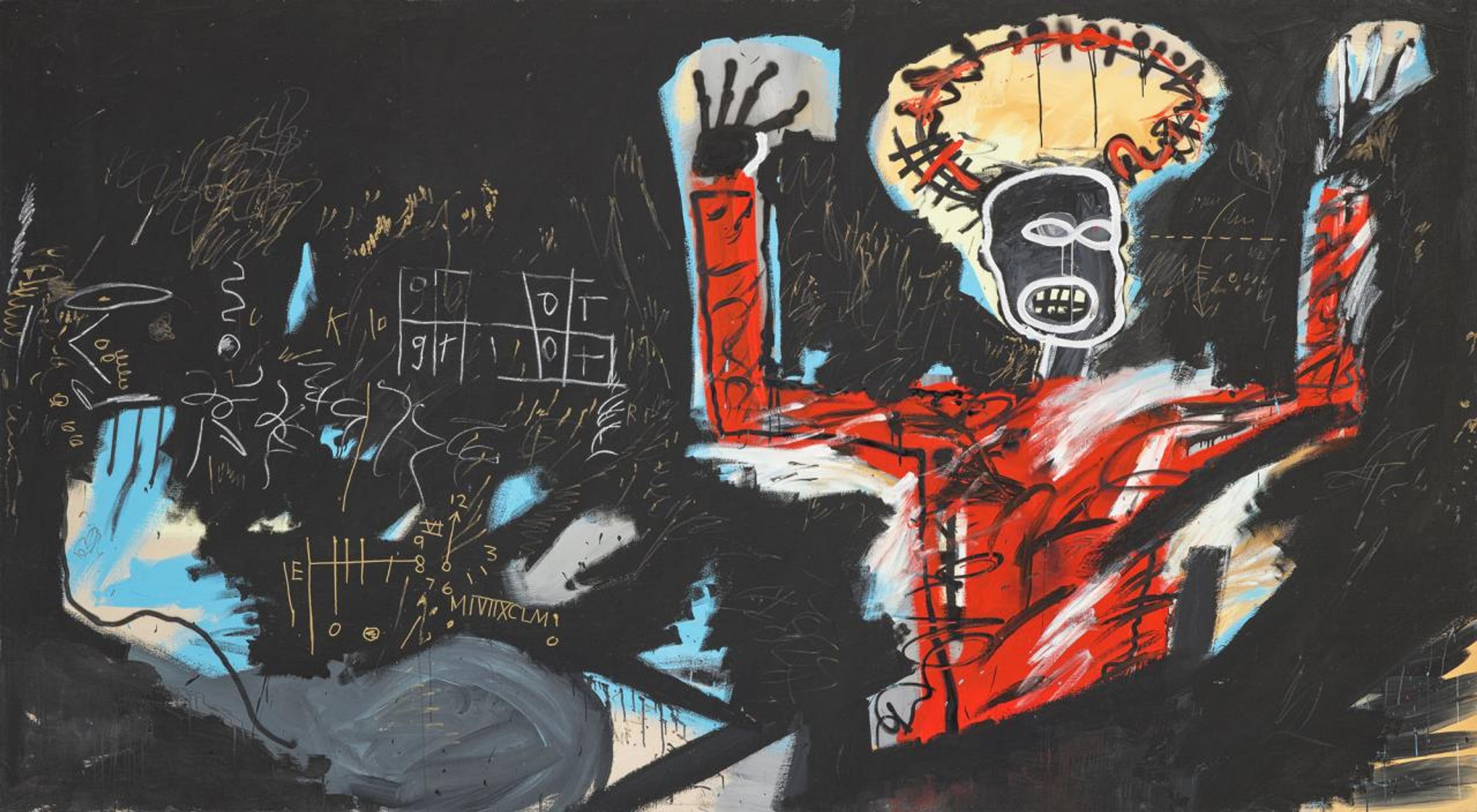

Further south, just outside the city limits, I felt slightly perplexed wandering “Out of the Box” (2023), an exhibition celebrating the 20th anniversary of Schaulager, a privately financed institution housed in an iconic Herzog & de Meuron building. Despite including art by the likes of Dieter Roth, Klara Lidén, and Gina Fischli, the show’s overarching curatorial theme, “Box,” seemed to be taken a bit too literally, both in various works and in the exhibition architecture itself. I preferred the relative tightness of “The Modena Paintings” at Fondation Beyeler in the northeast, which presented eight large-format Basquiat paintings from the summer of 1982 that had never before been shown together.

Beyond the fairs and the big institutions, there was plenty more to see in Basel’s galleries, pop-up projects, and in-between urban spaces. Obligatory was a visit to the Basel Social Club, just a stone’s throw from the fair, on the site of a former mayonnaise factory. The club, a kind of large-scale exhibition-gastro-performance-cinema-nightlife hybrid, was – along with the appointment of Elena Filipovic as the new director of the Kunstmuseum Basel – a constant topic of conversation at the fair. And not just because the fire department was called out once because the fog machine was turned up too high. The project was initiated in 2022 by Robert Fitzpatrick and Dominik Müller, gallerists respectively in Paris and Basel, as well as the local artist Hannah Weinberger, among others. Across concrete warehouses, a glass-roofed hall, and three floors of a former factory, several hundred works – including, in some cases, very large-scale pieces, such as a huge handbag by Gina Fischli, a room-filling light installation by Kitty Kraus, and a bright red balloon sculpture by Mandla Reuter – were on display, contributed by more-or-less established international galleries and art spaces. Had the Social Club become a supplement, an extension, or a counter-model to the usual, economics-driven fair formats? “Basel Social Club is not a fair,” the organizers emphasized incessantly – even though the art was, of course, for sale.

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Profit 1, 1982, acrylic, oil stick, marker, and spray paint on canvas, 220 x 400 cm. © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York. Photo: Robert Bayer

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Untitled (Woman with Roman Torso [Venus]), 1982, acrylic and oil stick on canvas, 241 x 419.5 cm. © Estate of Jean-Michel

On the way through the city, one repeatedly encountered art in public space. Those who followed Samuel Leuenberger’s exemplarily curated “Parcours” exhibition through the city sometimes ended up in enchanted places, such as the Birsig tunnel at the Schifflände landing stage, directly below the Hotel Les Trois Rois, where Laure Prouvost’s video No More Front Tears (2022) was shown. In the attic of the Museum der Kulturen on Münsterplatz, time seemed to stand still during Cally Spooner’s sound installation Dead Time (Melody’s Warm Up) (2022). And on Münsterplatz itself, the oversized strawmen of Kaspar Müller’s 8 Figures (2023) magnetized tourist selfies.

More hidden was the side-street cellar in the immediate vicinity of the Messeplatz where Eleonora Sutter had curated Hampton’s Cave (2023), a labyrinthine, slightly claustrophobic installation of seven black-painted sofas by Benjamin Lallier. At the front of the room, a painted paraphrase of Caravaggio depicted the seductive smile of Dionysus; closer inspection, however, was prevented by a transverse couch, which acted as a barrier between the painting and the viewer. A special spirit of bulkiness also radiated from Lorenza Longhi’s exhibition “Sentimental Pop” (2023) at Galerie Weiss Falk, where the artist had sealed the gallery’s street-facing windows with an opaque, milky coating. A series of collage paintings nodded in the direction of Andy Warhol with stylized flower shapes, but the artist simultaneously provided her images with frontal views of camera lenses, twisting the dynamic of gaze and counter-gaze.

Benjamin Lallier, Untitled, 2023. Courtesy: the artist and Heidi, Berlin. Photo: Robert Hamacher

View of Lorenza Longhi, “Sentimental Pop,” Weiss Falk Basel, 2023. Courtesy: the artist and Weiss Falk. Photo: Gina Folly

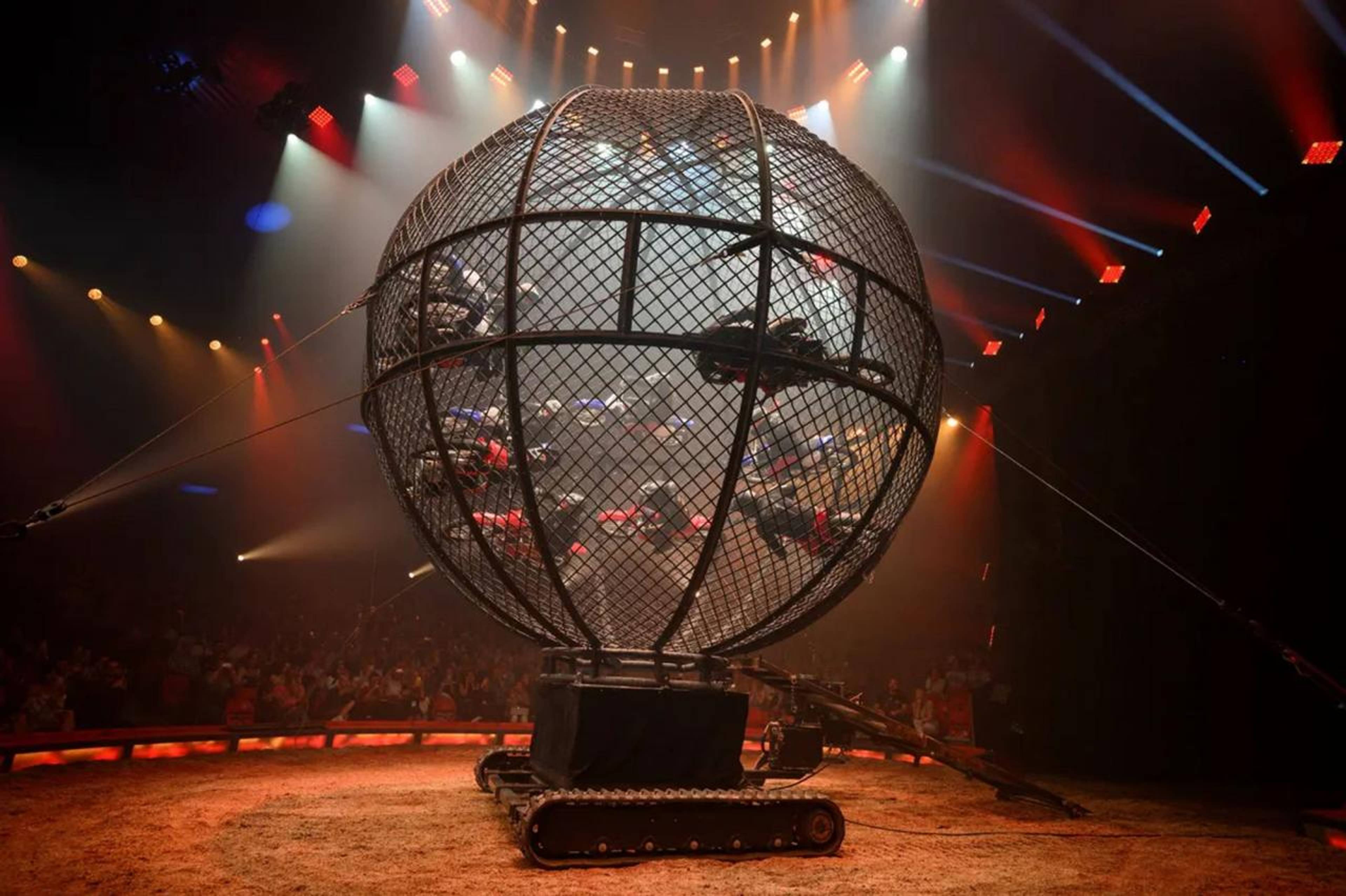

Finally, on Thursday evening, two gallery owners took me to see a performance at Zirkus Knie. Although the circus tent is directly opposite the fairgrounds, I’m confident that their audiences overlap only minimally, if at all. A truly dialectical neighborhood. I hadn’t been to the circus since I was a kid, and the force of the performance caught me off guard. It started with the smell of fresh sawdust, which filled the entire tent. As I marveled at the daredevil feats of acrobats from all over the world, I felt like I was trapped in a giant time machine from which all coolness had been sucked away. I clapped in time with hundreds of other spectators, marveled at the thirty-odd horses in the narrow ring, and laughed at the Schwyzerdütsch (Swiss-German) jokes of the intermission clown – which I did not understand – feeling alienated to the maximum. During the break, one of the gallery owners told me that he has been visiting the circus during the fair for twenty years as his own private Basel ritual, sensibly balancing one spectacle with another. Ten motorcyclists crisscrossing the interior of a steel sphere at seventy kilometers per hour are just as valid an image of the anthropocentric endgame we are living through as Algerian artist Adel Abdessemed’s single-shot video at “Unlimited,” Jam Proximus Ardet, la dernière vidéo (2021) – a loop of a burning ship sailing across the Mediterranean.

Kaspar Müller, 8 Figuren, 2023. Courtesy: the artist and Société, Berlin. Photo: Sebastiano Pellion

Adel Abdessemed, Jam Proximus Ardet, la dernière vidéo, 2021, 6K video projection, color, 1:40min (loop), dimensions variable. ©Adel Abdessemed / Paris, ADAGP 2023

___

![Jean-Michel Basquiat, Untitled (Woman with Roman Torso [Venus]), 1982, acrylic and oil stick on canvas, 241 x 419.5 cm](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/syotmk9q/production/e5042fcb8c6245564da86ec0bcc1cb9fc56d1a19-1280x730.jpg?w=3840&q=75&fit=clip&auto=format)