The movie had been cosmeticized to death, they said.

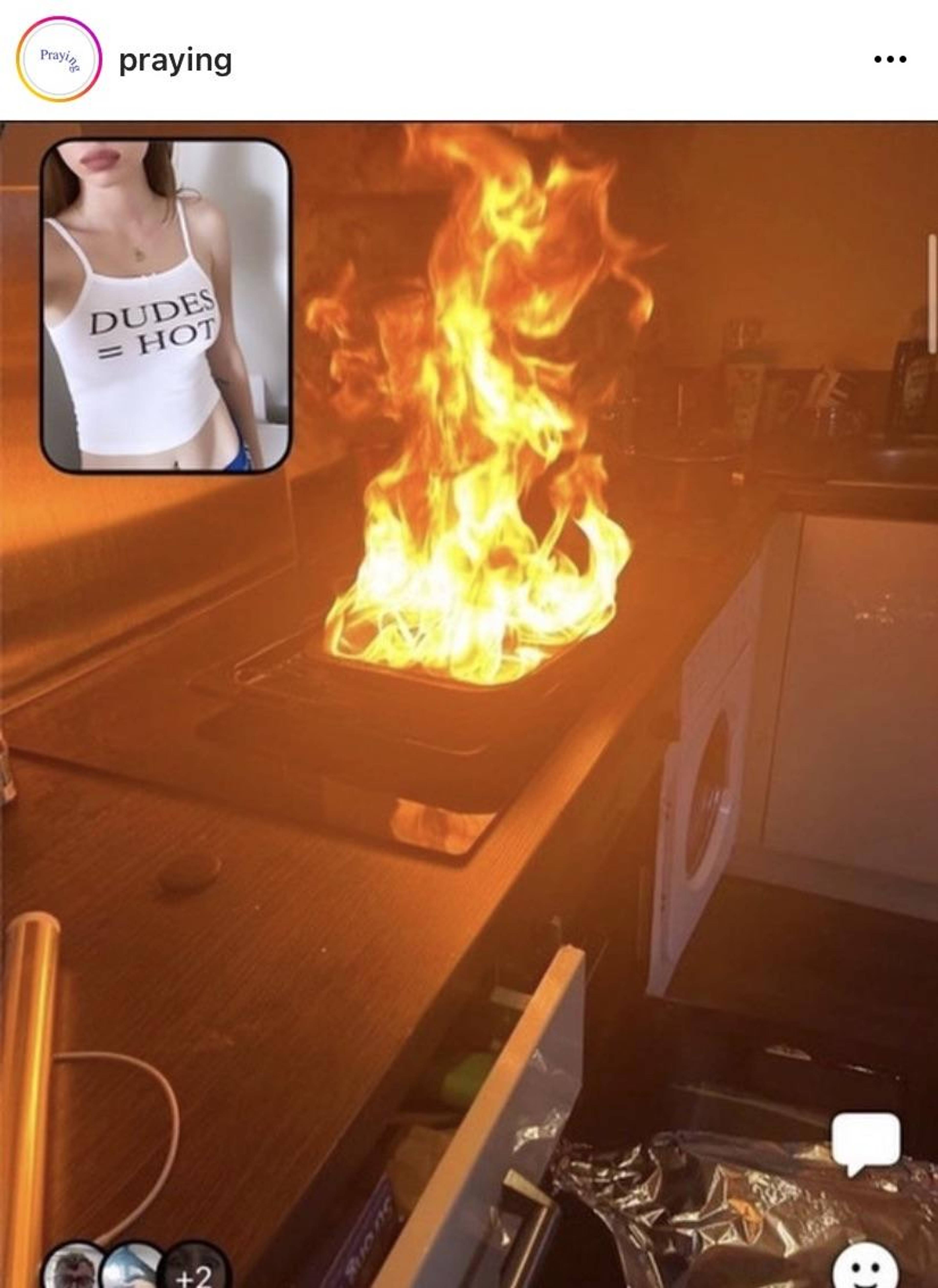

I started seeing something different — at first occasionally, then in overwhelming numbers — cropping up on Instagram Stories. Images capturing moments of contingency, a little frazzled, unpolished. Pairs of photos, one small, embedded in the upper corner of a larger one. The harsh edges of snapshots softened into pleasant squircles. A new media format, an anti-Instagram, was breaching. Trickling into the dominant platform’s calibrated stream. It came, its PR team tells us, for the noblest of reasons: to liberate us, the immiserated, insecure masses, from the tyranny of the constructed image.

BeReal, the platform behind the phenomenon, hit the market in 2020, but saw a 315 percent growth spike in 2022. Anecdotally, I started clocking it in maybe March, drawn to its simplicity. It was kind of an enigma, bizarrely elegant, embraced by the “with it” and non-acne-prone.

The app’s mechanics are as follows: it nudges users across a geographic region at a random time of day by a push notification. A timer engages a two-minute countdown. Upon opening the app, a photo is snapped with the front- and back-facing cameras, producing both a selfie and a reverse shot. The photo must be posted without filters. It will be visible in a feed only to a user’s “friends,” and only to those “friends” who have also posted face. The feed resets every 24 hours. There are no “likes.” There is only participation, presence. Pure visibility.

BeReal meme. Credits: @mxlodycore on Twitter

Recounting these rules, I couldn’t shake the feeling that this all sounds a bit like the Dogma 95 Vow of Chastity — the camera must be hand-held; shooting must be done on location; optical work and filters are forbidden. Those rules belong to a declaration penned in 1995 by the Danish filmmakers Lars von Trier and Thomas Vinterberg, who wanted the avant-garde to carry out a “rescue action,” resuscitating cinema from its decadent bourgeois romanticism, mired in obsession with auteurism and glitzy FX. In the accompanying manifesto, von Trier and Vinterberg write:

Today a technological storm is raging of which the result is the elevation of cosmetics to God. By using new technology anyone at any time can wash the last grains of truth away in the deadly embrace of sensation.

Anxiety about social media’s inauthenticity, the motivating force behind BeReal, is a shade off from debates that have reverberated throughout the history of the recorded image . Documentary cinema in particular has been fraught with questions of its truthfulness since practically its genesis, and even narrative fiction film, with movements like Dogma, has sought to return the recorded image to “truth” through various formal maneuvers — in their case, a kind of asceticism.

Does Instagram purport to be a documentary? Does it want to be? Implicitly, the social contract of social media is that it’s produced from real life, but no one, in their heart, believes that it’s real . All recorded images depart from the same lie of omission: selectivity, enforced by the borders of the frame. The point here is not that authenticity is fake, or even that the internet killed it. More precisely, I’m curious about the way that technological history has unfolded such that the feeble notion of a stable fixed self, a tough sell in the first place, became fertile ground for a ubiquitous business model. SaaS: Selfhood as a Service.

Apparently, like most early-stage tech companies, BeReal is not currently profitable. It has been financed by outside investors, most notably, the venture capital firm Andreessen Horowitz, one of Instagram’s earliest funders. Before he was a VC, Marc Andreessen built Mosaic, the first user-friendly internet browser, as a university project in 1993. Far be it for these powerful forces to funnel $30 million into an app without expecting that it will one day yield returns. What BeReal’s roadmap to profit might look like, I’m not entirely sure. One paranoid hypothesis: accruing an archive of users’ unfiltered faces (compulsory selfie) plus eyeline-match images of their surroundings (implied location) will become a hugely valuable dataset. Show me a corpus of user-generated content and I’ll show you a Palantir scandal waiting to happen — a facial recognition system in the making, an AI ethicist having a panic attack. The Laura Poitras documentary practically makes itself.

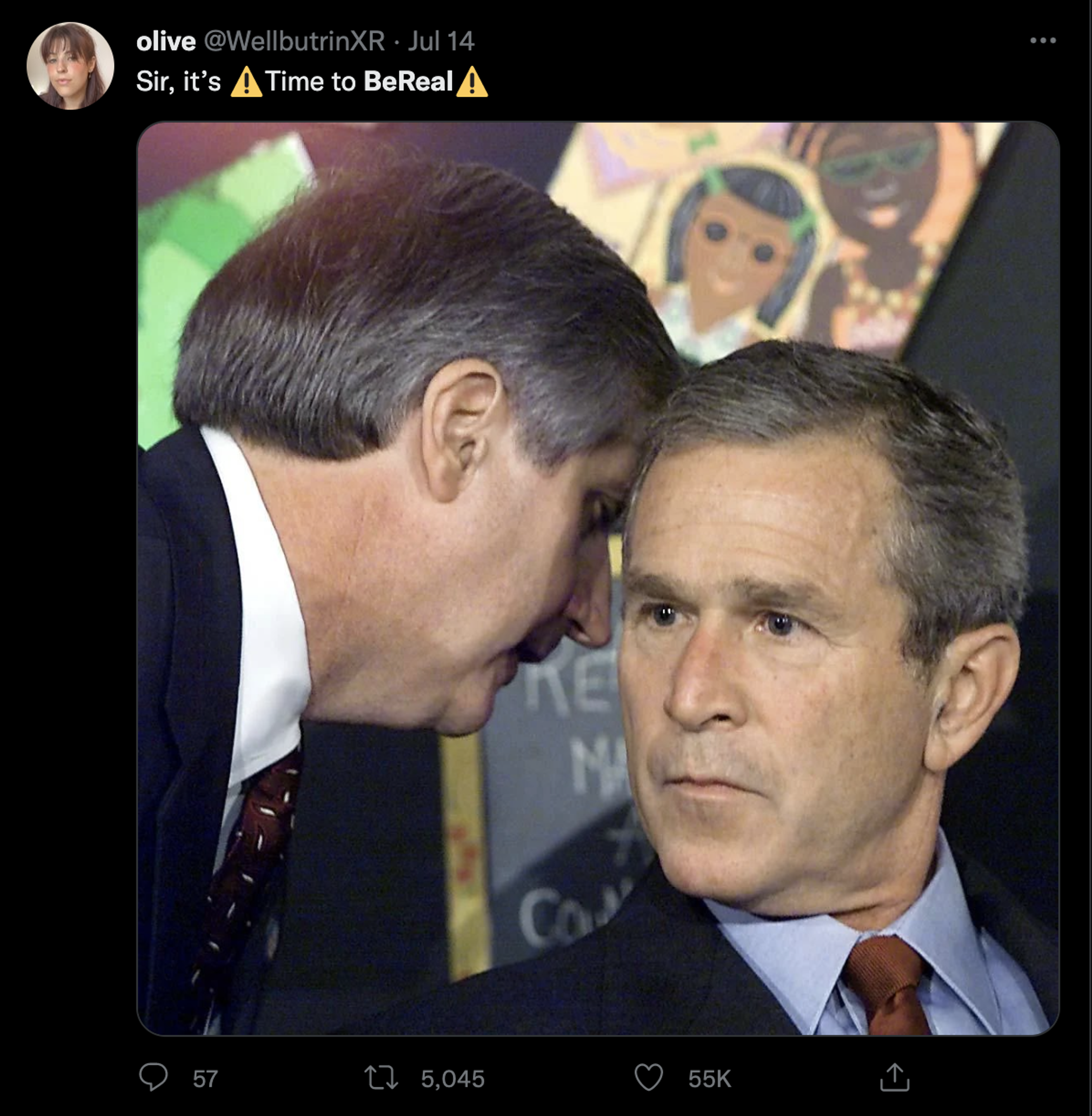

BeReal meme. Credits: @wellbutrinxr on Twitter

Probably it won’t be that dystopian, though, just corrosive in a boring way. Beyond manufacturing urgency (two-minute countdown!), BeReal demands all-in engagement. Lurkers, look elsewhere. You can’t view the feed unless you, too, have posted a photo that day. If your face dodges the frontal camera, a concerned notification will nudge you: your friends want to see you! These gamified dynamics purport to catch you off-guard — by design, because that’s where the authenticity happens — but also, conveniently, produce the kind of repeatable adrenaline rush that courts habitual, even addictive engagement.

Kranzberg’s First Law states that “technology is neither good nor bad; nor is it neutral.” But each piece of technology has a pyramid of value — it enriches certain people, usually at others’ expense. The dynamics by which it does so can be more or less obvious; more or less obscured behind clever, mediagenic marketing rhetoric. I don’t think the people who made BeReal are concern-trolling, or even particularly canny. I think that, like a lot of tech marketing departments, they are understandably inclined towards believing that their product will make the world a better place. I don’t know if people really feel less FOMO there, less ashamed of their physical insecurities. I find BeReal more anxiety-provoking than fun, but that’s true of a lot of supposedly fun things, like trivia and music festivals.

Some people, though, particularly of a Gen X persuasion, seem to take it at — sorry! — face value. One commentator, writing for parents.com, coolly states that BeReal’s constraints are designed to “force users to be as authentic as possible.” Haha scary!! Deleuze said something once, and I can’t be bothered to Google it so I’ll try to manage from memory, about how repressive forces don’t stop people from expressing themselves — to the contrary, they force them to express themselves. Or, in the words of my fave, Byung-Chul Han: “Today’s surveillance society does not attack freedom. It ensures that we voluntarily expose ourselves to the panoptic gaze.” In the BeReal corporate imaginary, all the tight constraints are meant as a bulwark against personal branding — but doesn’t the app do the exact opposite? Authenticity has long been one possible flavor of online self-presentation (or, to distill it into candidly neolib terms, “personal brand”). In this case, it is merely the only available one.

Still from Breaking the Waves, 1996, 159 min.

The most famous rule of Dogma 95 became a maxim of the movement: The director must not be credited. In part, von Trier and Vinterberg were responding to the increasingly accessible terms of film production: Today a technological storm is raging, the result of which will be the ultimate democratization of the cinema. For the first time, anyone can make movies.

This was two years after Marc Andreessen launched Mosaic; he then co-founded Netscape, the browser that defined the early commercial internet. And then came the platforms. Connecting us to each other; democratizing the means of image-production; readymade audiences appearing for all. Instagram isn’t a documentary, I think, but it might be cinema. Like Metahaven argue in Digital Tarkovsky, the average user regularly spends the equivalent of Stalker’s runtime looking at their phone. (My weekly screen time reports check out.) To borrow a tired truism so often applied to these social networks, marketed as free at the point-of-use: they make you believe you’re the producer, when really, you’re the product.

The Dogma 95 Vow of Chastity ends with a renunciation.

“I swear as a director to refrain from personal taste! I am no longer an artist. I swear to refrain from creating a “work,” as I regard the instant as more important than the whole. My supreme goal is to force the truth out of my characters and settings. I swear to do so by all the means available and at the cost of any good taste and any aesthetic considerations.”

The filmmaker, in their pious adherence to the Vow of Chastity, sets their authorship aside. They pursue the moment, endeavoring to capture it, unfettered. A direct opposition is set up, here, between personal expression and truth. Except that, of course, that isn’t how things ended. Lars von Trier got super famous by making stunning if extremely hard-to-watch movies and is, depending on your point of view, either ironically or unsurprisingly credited as the inventor of an important film-historical movement. And the obsessional directness of his work from the 1990s gave way to more lenient, ornamented productions when budgets began to allow. Highlights from the post-Dogma days include Dancer in the Dark, a musical starring Björk, who was so traumatized by working with von Trier that she swore off acting altogether.

Truth is virtue, and we strive in its direction through obligatory disclosures of self-as-personal-taste.

Now widely considered an auteur himself, von Trier’s persona is perhaps the largest obstacle to his, forgive me, personal brand . His films, unparalleled in their elegant brutality, are totally, self-evidently products of the man who made them. My intention here isn’t to suggest that these two threads — BeReal and Dogma 95 — are totally isomorphic, or that we’re all heading in von Trier’s direction. I guess I’m more interested in reading them against each other with an eye to the technical forces, which are really market forces, that make claims of “authenticity” so wearisome — yet keep churning out new versions of those claims, new ways of repackaging them in dressed-up (or dressed-down) forms.

The primary rule of Web 2.0, defined by “real name” policies and blue checks, is that the director must be credited. What does that reveal about the direction that media technology has taken in the last two decades? As the tools of narrative-making have diffused, so, too, has the demand that we use them honorably, “authentically.” Truth is virtue, and we strive in its direction through obligatory disclosures of self-as-personal-taste. The illusion of freedom — in this case, from self-esteem-lowering fakery, I guess — turned out to be a remarkably efficient way of incentivizing auto-exploitation. Contra-BeReal’s PR rhetoric, it’s not that, with the rise of their platform, there’s no more personal brand — now, there’s no brand besides the personal.

I go on Instagram because it is more entertaining than watching TV. Feature-length films tax my attention span. Many hours I’ve wasted this month — maybe the equivalent of von Trier’s filmography, or Tarkovsky’s, to quantify it in Metahaven terms — tapping away at the screen with my debilitating fake nails, which I got because I saw others showing them off on Instagram. I wondered if having my own would make me more beautiful. They just made it harder to write, so instead, I scroll. Unfree from fakeness but liberated from narrative structure. An endless procession of flat, desirable content, calibrated to my exact preferences. I become what I take in and then make more of it. And so on, in a tightly wound algorithmic feedback loop, ad infinitum. By being porous, I become myself. There’s a certain jouissance to the fakery of it all. Long live godly cosmetics!

Still from The Idiots, 1998, 117 min.

___