Since the 1990s, there have been two categories of Venice Biennale. The first are organized under a title so vague that it could very well belong to any exhibition, featuring a list of the artists of the moment, a compilation combining the zeitgeist and the personal playlist of its curator. In the second category, I place those which assert a vision of art — a point of view on its evolution — and try to articulate it in space by using a curatorial grammar, the mise-en-espace. “The Milk of Dreams” belongs to the latter category; whether one opposes its premises or adheres to them without reservation, it has the rare merit of saying something; and this is reason enough to praise Cecilia Alemani’s work. Despite its being the first major biennial since the outbreak of the pandemic, and inaugurated during a time of war, Alemani’s exhibition testifies to a real confidence in the power of art: Rather than use works of art as testimonies or markers referring to positions outside the field of art, the New-York based curator arranges original voices in the space, organizing counterpoints, dialogues, and echoes. It is this “operatic” dimension of the exhibition where previous editions have certainly fallen short. One could say that they simply lacked style, that they were devoid of style, that is to say, devoid of a principle of organizing space that associates theory with formal premises, reducing curating to an address book and a laborious research file.

Since I am commenting on “The Milk of Dreams” as a curator myself, I am compelled to establish a link between this exhibition, and the last pre-pandemic biennial, held in Istanbul in autumn of 2019, which I curated: “The Seventh Continent” also evoked a post-human world, exploring the Anthropocene through the image of an immense “continent” of plastic floating in the ocean. Alemani deals with a similar subject, but from a radical, yet extremely logical angle: the problem is also patriarchy. In direct opposition to the wave of micro-anthropocentrism (i.e. the influx of identity politics) which swept through the art world in the 2010s, she approaches the post-human via the eco-feminist paradigms of scholar Donna Haraway and philosopher Rosa Braidotti, although this term is strangely not named as such by Alemani.

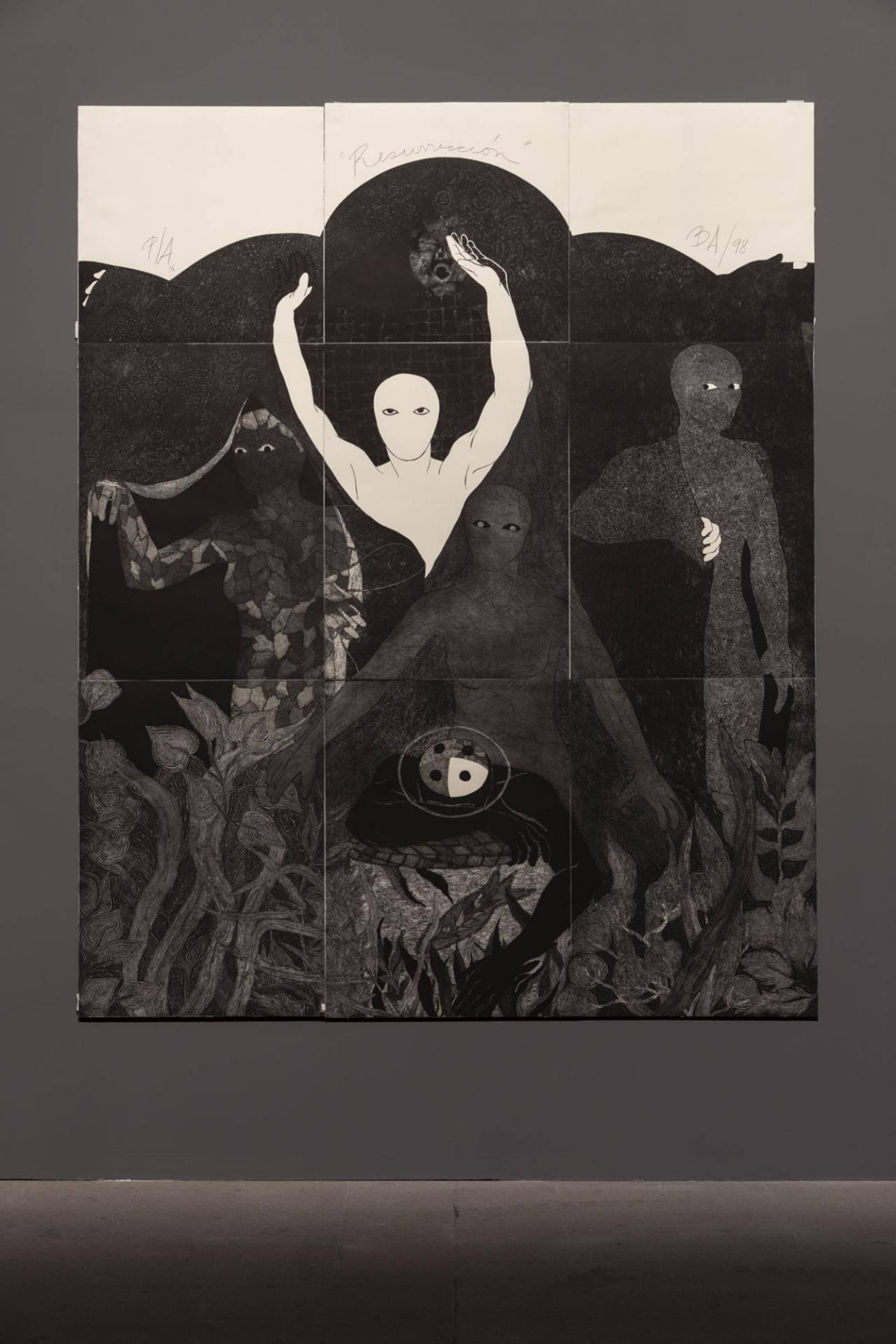

Precious Okoyomon, whose huge installation, To See the Earth Before the End of the World (2022), closes the exhibition at the Arsenale, represents a kind of manifesto; the various historical “capsules” set up throughout the show each refer to articulations between the human and one of its outsides: the machine (“Seduction of the Cyborg”), the algorithm (“Technologies of Enchantment”), language (“Corps Orbite”), the tool (“A leaf a gourd a shell a net a bag a sling a sack a bottle a pot a box a container”), and magic (“The Witch’s Cradle”). In this way, “The Milk of Dreams” takes into account the crisis of scale which questions our anthropocentric assumptions. Today, the main agent of human history belongs to the invisible and the intangible: viruses, gases, degrees of heat and cold, fluids ... It is not by chance that Alemani, in her temptation to write a parallel, necessarily incomplete history of art, gives pride of place to surrealism and its mediumistic or spiritualist derivatives. More than ever, artists today are tasked with giving us a view of the invisible. To mention only those who caught my attention: Spanish healer and self- taught artist Josefa Tolrà and Italian medium Eusapia Palladino are part of this quest to rewrite art history through the inclusion of ignored voices. In this register, we can also mention Chilean poet and artist Cecilia Vicuña, Brazilian artist Lenora de Barros, or the Cuban printmaker Belkis Ayón, who was the subject of the magnificent exhibition at the Reina Sofia.

Belkis Ayón, Resurrección, 1998, collography on paper, 9 sheets, 263 x 212 cm

Cecilia Vicuña, NAUfraga, 2022, installation, ropes and debris found around Venice, oil on canvas

The scale of this rewriting enterprise is such that one could speak of a pursuit of “historical rescue”, as termed by Walter Benjamin — the reversal of history as “written by the victors”. The focus on André Breton’s Nadja, previously known only through the 1928 novel by the lider maximo of Surrealism, but also the place given to photographer Claude Cahun, and artists Remedios Varo, Dorothea Tanning, and Leonora Carrington, testifies not only to an updating of the Surrealist movement, but also to a valorization of the quasi-shamanic position of the artist, to reweaving the historical narrative through the notion of reception. It is just as important to receive as to produce, this exhibition seems to say. The human process by which one produces while receiving is gestation — birthing. This figure runs through the entire exhibition, linking its eco-feminist premise to a strong idea for the art of our time. Contrary to what the philosophers of speculative realism say, relationships take precedence over isolated objects. As the physicist Karen Barad reminds us, everything that exists emerges from a relationship: the doing takes precedence over the thing.

Zheng Bo, Le Sacre du printemps (Tandvarkstallen), 2021, 4K digital video, colour, sound 16:17 min.

Another work emblematic of Alemani’s point is Zheng Bo’s video Le Sacre du printemps (Tandvärkstallen) (2021), which presents an upside-down image of a forest that has become an object of sexual interest for a group of young men. According to the Italian philosopher Emanuele Coccia, species are constantly changing the world, obliged to engage in dialogue and sign pacts with others. It is important to refer to this theoretical context since “The Milk of Dreams” stages the common challenge of feminism and the ecological struggle: To put an end to systems of domination inherited from the Neolithic era with a program of control which, today, finds its limits between the two infinities, the tiny and the immense, the viral and the global. As a result, Alemani’s exhibition seems to me to be more about the pre-human than the post-human: A kind of positive wave runs through the biennial, that of a possible transformation of bodies and minds. In Alemani’s words, “despite the climate that forged it, this is an optimistic exhibition, which celebrates art and its capacity to create alternative cosmologies and new conditions of existence.” Pre-human rather than post-human, because the exhibition presents a kaleidoscope of positions that contribute to a re-composition of a possible image of humanity through the motif of bodies in search of redefinition: before technology, before the planet, before themselves. One can only regret the low proportion of young artists included in this historical remix or even their lack of relevance at times. Rediscoveries, which dominate the current art market, generally outweigh discoveries. “The Milk of Dreams” succeeds in reconfiguring the software of art and injects all of its energy into it; as for its immediate future, the work remains to be done — no doubt by the likes of Dora Budor, Mire Lee, or Marianna Simnett.

Mire Lee, Endless House: Holes and Drips, 2022, multiple ceramic sculptures on a scaffold, lithium carbonate and iron oxide glaze liquid, pump, motor and other mixed media, 1.8 x 2 x 4 m

___

“The Milk of Dreams”

59th International Art Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia

Central Pavilion & Arsenale di Venezia

23 Apr – 27 Nov 2022