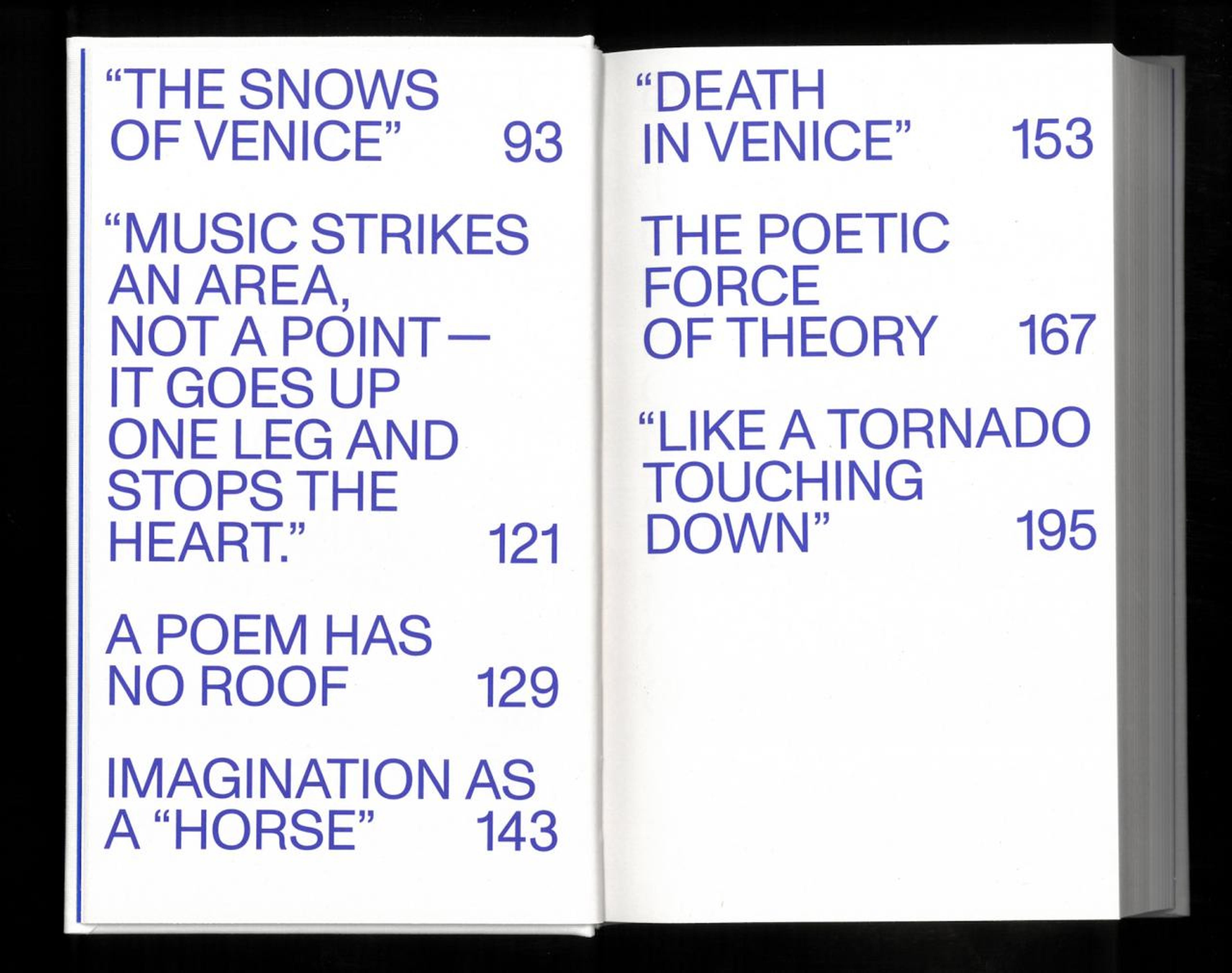

Carina Bukuts: You coined a term that comes to the fore time and again; recently, it was in fact the title of your exhibition at the Württembergischer Kunstverein in Stuttgart: “Gardens of Cooperation”. Your latest book The Snows of Venice is a cooperation with poet Ben Lerner and perhaps also rather such a garden. What are gardens of cooperation and who plants them?

Alexander Kluge: As chance would eventually have it, through my employee Dr. Combrink I came across Ben Lerner’s Lichtenberg sonnets . It left me astonished that an American poet from New York would write about a hero of the Enlightenment: Lichtenberg, one of my favorite authors. I was impressed how Lerner is proficiently skilled not only to pen beautiful words, but to coalesce thought and word. So, I wrote stories on individual lines in Lerner’s poetry. In the past poets used to correspond with one another by writing each other letters. In this book there are many gardens of cooperation: Thomas Demand’s photography and also both of my favorites by Paul Klee. To begin with there’s Angelus Novelus (1920), which Walther Benjamin interpreted as the angel of history. To me, this incredibly sensitive prophet seems a little impractical as the answer to the challenges of our ignorant and murkier present time. I rather see a second angel by Paul Klee: Prickle, the Clown (1931). I placed this alongside the angel of history. Then I’ve got a practitioner and a joker who cooperate with one another. This is how gardens of cooperation arise. No one plants them, they just grow. We are related to each other in the subterranean. The gardens can’t actually be planted, but one can care for and respect them, and then they grow of their own accord.

Is there a difference between cooperation and collaboration?

They’re just two different words. One means working together and the other means working together as well.

Cooperation sound considerably more bureaucratic to me, like a trading partners’ meeting.

You’ve hit the nail on the head there! Let’s say collaboration then, but you could also say constellation. That’s an even nicer expression, it comes from the stars. Celestial bodies can’t be held together with beams and screws, but by gravity. By authority of their very substance they possess a gravitational force that can assemble a solar system, a Milky Way, as if it were a building. Gravity is stronger than any concrete, stronger than any lock joint or iron compound, and it connects people. When such gravitational interaction is at play in poetics then constellations emerge that are just like gardens of cooperation. Save the fact gardens would be on earth and the others in a starry firmament.

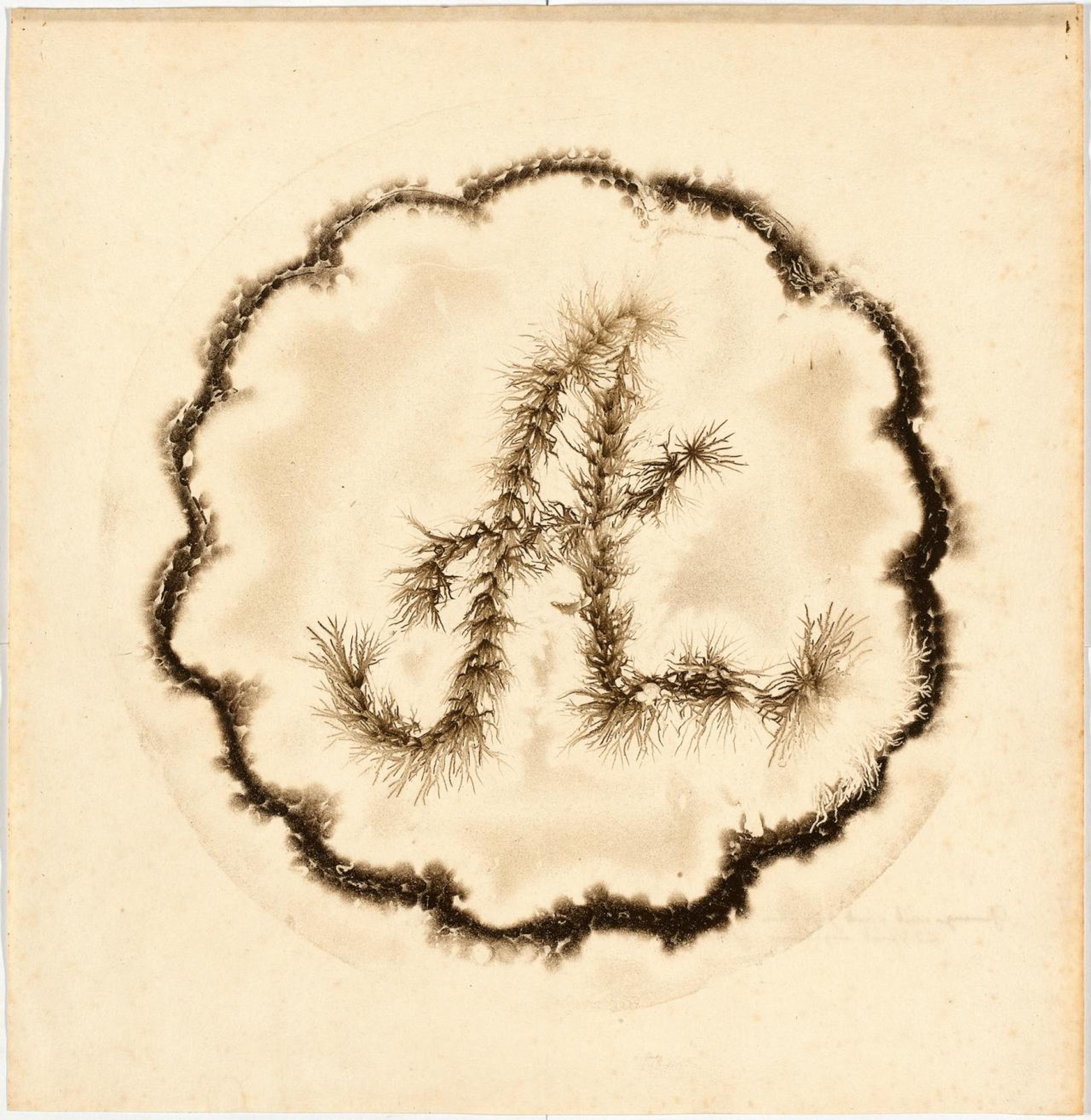

Adolf Traugott von Gersdorff Lichtenberg Figure

This links to a verse of Ben Lerner’s that very much captivated you: “The sky stops painting and turns to criticism.”

It threw me that one can say the sky stops painting and turns to criticism. Where does the term criticism come from? It is in fact the pioneering concept that spearheaded the enlightenment. It also played a large role in the romantic period; for Tieck and Schlegel's criticism was a productive altercation with something. This manner of criticism, this emphatic term for criticism, that it is to be found unexpectedly in a poem, delights me.

when bricks are shattered there’s still a rubble-strewn city of clinkers that can be salvaged

Your response was a piece of prose about a grievance in the sky, a bomb attack.

When these silver arrows emerge from the sky it can be quite unearthly, and then beauty is snuffed out. Poetry doesn’t exist to filter out beauty, it employs truth and criticism because, as Lerner alludes in a very meticulous manner, something went wrong. Went wrong in that a group of bombers, and nowadays even drones, stand in opposition to those sitting in basements. This is an inequality that goes far beyond what Marx wrote in the Capital. It’s actually unbearable because they can’t even surrender. This means that the only achievement of war, namely the ability to stop and raise the white flag, is also withheld. This greatly affects me. I lived through 1945 as a child and didn’t understand it. Later I tried to understand through the accounts of others and today I recognize it again in Aleppo, albeit in an even further aggravated form. I have to put it this way: when bricks are shattered there’s still a rubble-strewn city of clinkers that can be salvaged. It is the women there who relay and rebuild. In Aleppo they can’t even do this anymore as there’s only crumbling concrete left that veritably fails to pass as desert. In fact, sand would be a useable, fertile alternative when pitched against this new world of dust-debris.

If poetry exists to filter out truth, what does prose do in contrast then?

Poetry is a form of concentration I truly admire. I myself can’t write poetry, but through film I can create, for example, triptychs that come quite close to poetry. I can also do something similar with music, but not with words because I learned mine from people who weren’t so inclined to consolidate them. When I want to densify my words, which I do, then I have to either fragment them or create discrepancies, friction and gaps, in that I manufacture a sort of concentration of words. I can’t do it solely with the innate power of words like Ben Lerner or James Joyce for example, both of whom I really admire. In this sense, poetry as a form is actually suited to supplementation. You can take a sentence from Friederike Mayröcker and add a whole block of prose under it. My prose diligently bows down to a poetic phrase. A line of poetry is the captain and I march in step behind, it is the Pied Piper of Hamelin and I run after. I adore poetry but I can’t write it. Prose simply doesn’t compress the density of words, it is instead an extensive but two-dimensional form of expression.

Gerhard Richter, 1972

There’s a trail of action/reaction that can be traced throughout the whole book. Not only in your reactions to Lerner’s poetry but also in R.H. Quaytman’s paintings. She discovered a print of Luther under Klee’s Angelus Novelus and detailed it in in her series Chapter 29 (2015). In turn, you also responded to Gerhard Richter’s photography.

I was amazed to see this green in Gerhard Richter’s photographs. I certainly hadn’t expected that from him. It is the green of Venice’s lagoon with which he has entrusted us. Reacting to one another is a very pleasant way to interact with others. One can of course touch with the body (he touches CB’s hand), but also with a body of thought; the cooperation is then a matter of trust and doesn’t sound so bureaucratic anymore. I’ve found that when I talk to someone, I become more individual than I was before. One isn’t homogenized through it, instead all three parties gain more self-confidence which really forms the crux of it. Hence, why I find it fitting to use the word “constellation”.

The less of a whole steamer a book is, the more freely it can travel down the Mississippi

I remember some interviews from 2017 in which you were asked what possibilities exist within the walls of a museum that cannot be realized through film. In a similar vein, what is possible in the book as a format?

There are considerable differences. A book’s métier and that of film and exhibitions are entirely independent worlds. I can’t do both parallel and also not have them simultaneously in my head. I have to tune myself into either one or the other separately when I decide to make them. A book is like a boat or a raft. There I can make connections over a period of time. A film functions very differently to a book, it can’t adhere to anything, it doesn’t obey the rules of grammar and hardly forms sentences. It can pretend to develop phrases and a storyline, but the essence of film is actually individual takes that move around.

Film as iconoclasm?

Exactly. Films actually reduce images rather than actively producing them. In this respect an American narrative film isn’t really a proper continuation of film history, unlike a collection of oil paintings or a piece of theatre. Books are beneficial containers or rafts upon which we can float through time. The less of a whole steamer a book is, the more freely it can travel down the Mississippi. Film, in turn, is an artwork in and of time. A film is realized in the mind, not on a canvas. We say “movie” because we are moved by film, but it also moves as well, so there’s a double meaning.

Scan from “The Snows of Venice” © Spector Books

In exhibitions film operates in a space that is substantially more flexible, allowing viewers to move around the room and the film. While a film can be viewed collectively, viewing the exhibition or reading a book is mostly an individual experience, which leads to a very different form of engagement.

Precisely. Film can be understood as mutable theatre where the viewer is held for one and a half hours in a particular time. The exhibition possesses something incredibly liberal. I first understood this two years ago and think that the history of film can progress there whereas it is stagnant in the cinema at the moment. I find books on the contrary, the hardest to accomodate in an exhibition. I would actually like to retrace everything with you and return to the elements, the individual words. What we can do very well, for example, is create a poster and use a word in a sentence: Time isn’t “good-natured”. You can write that on a poster, tag the word “good-natured” and then program a film to play on your phone so that you can watch a scene depicting how time isn’t good natured.

The vision of the burning angel standing before god and singing to him is rather unsettling for me

An attempt at translation. Nevertheless, not everything can be translated 1:1. At certain points in his poetry Ben Lerner addresses the discrepancies between both of your languages: English and German.

Even the word love is so general. Something has to be done so that it gains traction and doesn’t simply float about poetically. Close to the skin is already more concrete, intimacy is a good word. If I translate this into Russian and from there into a Latin language like French, each time a new factette emerges quite unlike its predecessor. A description of a kiss is exactly the same. A kiss is alien to the alphabet. There is no methodical approach by way of words. We could write seven pages and still not reproduce the sensation of a kiss. The word “pun” in English, for example, is difficult to replicate. Even though I know we are aware of what a “pun” is in Saxony and Saxony-Anhalt, it doesn’t fall under the umbrella of this word. It’s common courtesy in Halberstadt, my home town, to include a joke into the conversation as a little distortion of perspective. You wouldn’t respond to “nice weather” with “yes, nice weather”. One doesn’t do that, it’s just rude. Someone says, “nice weather” and you respond “yes, nice weather to piss like a pig”. One has to say something with a bit of variation, an offer of a little divergence. It’s not yet a fully-fledged laugh or joke but a small slice of nuanced reality that doesn’t depict what’s going on in a linear way.

Now that you mention the weather, I just realized that we haven’t spoken about the meaning of snow in this book. It constantly arises in the texts, but never makes a visual appearance.

“Snow falling softly (Leise rieselt der Schnee)” is a childhood experience of mine. Imagine an evening at dusk, the light blurs somewhat and then snow usually begins to fall lightly. A certain evening warmth is needed, otherwise it won’t come. There’s something mysterious in it and as a child I felt at home with that. There was this phrase that reminded me of the memory: “In medieval angelology there are nine orders of snow”. That’s a verse from Ben Lerner and now I’m searching in this childhood snow experience for the idea of angels. If you told me there’s an angel in this glass here, I wouldn’t believe you because my general state of existence is not to presume. I also wouldn’t associate angels with blue sky. On the other hand, the vision of the burning angel standing before god and singing to him is rather unsettling for me. I’m comfortable with the image of the snow but there’s also mud. There’s the story of a WWII paratrooper on Mount Etna, a disorientated soldier who encounters snow on the mountain. I can imagine him in his jump boots trudging through the snow, something that he is still in awe of and takes as mysterious. With guns he can’t shoot windmills. There you see handling what once was snow, namely mud, is extremely different.

Venice, 1971 Photo by Gerhard Richter

Sleet doesn’t float down either. It would never fall softly as mud is heavy.

Sleet comes down in sheets. An avalanche of mud triggered by El Niño has incredible power. These are images we have to deal with very seriously because the earth is doing something, and as humans we also have the ability to cause additional things like this. When we cut down trees too opportunely, we are faced with avalanches. When we treat our climate as crudely as we do then we’ll be confronted with an increase in avalanches. In capitalistic process there are solid locations, but there’s also liquid, streams of money. Capital virtuously instigates flow between people in an exchange economy, but the sludge that the finance hub of London is stuck in, the capitalistic swamp, that isn’t tradeable. A most gruesome of way of sinking into the morass.

The idea of sinking appears a lot when flicking through The Snows of Venice. You said earlier that a book can be a raft or a container but that it but shouldn’t be a steamboat. That reminds me of all the cruise ships in Venice. Their sheer size and destructive force are irreconcilable with this small, rather mystical city.

Yes, those floating skyscrapers. It wasn’t long ago that they could actually moor at the city’s waterfront. They aren’t allowed to do that anymore though. But they do look brutal, it’s as if dinosaurs are trudging through the city.

What’s happening there is also something that occurs often in this book, or in the exhibition at Fondazione Prada in Venice. Some sort of force tries to breach the mysticism of the city. The title of the exhibition also reflected this: The Boat Is Leaking. The Captain Lied. An Illusion is dispelled. In one of your stories there’s also the address made by the violinist on the Titanic, who continued to play until the ship sunk.

Whole forests were integrated in the teak of the titanic. It is my wish that we reinforce this wood while there’s still time so that we’ll have a life raft until two in the morning.

Translated by Sarah Crowe

ALEXANDER KLUGE is a filmmaker, writer and a founder of the New German Cinema. His work was on view at Fondazione Prada, Venice, Museum Folkwang, Essen; Württembergischer Kunstverein, Stuttgart, and most recently presented at The New Alphabet at HKW, Berlin.

CARINA BUKUTS is a writer and curator based in Berlin where she currently works at frieze magazine. She is the co-founder of PASSE-AVANT .

Snows of Venice is published at Spector Books and was launched at Spike Berlin in January 2019.