Bill Kouligas: It’s good to see you. It’s been a long time.

Mark Leckey: How are you doing?

BK: I’m good, I’m good. I’m in Berlin. I’ve been traveling quite a bit the past month, but I got back yesterday. So, I’ll be back home for a minute, which is great.

ML: Where have you been?

BK: I was in Milan for two weeks. I did a big presentation during the Salone del Mobile, of a collaboration between [my record label] PAN and Nike. I designed a shoe for them, and with that excuse, built a whole world around it, which was more where my interest was. I mean, I love design and its principles and its history and all that stuff, and it was an interesting process to work on a sneaker, using the same creative research and methodology that I would use for an art book or a DJ setting or a sound piece. But within that process, I built a whole environment, which was then presented at Dover Street Market in Tokyo, then at events in Athens, London, Venice, and so on.

ML: Had you worked with a brand like that before?

BK: No. They wrote me because they were interested in working with a contemporary electronic music label to remodel an Air Max they made in 1991. It’s the Air 180, which was the first running shoe in that series. But because of its very breathable mesh material, all the raver kids were using it in the UK. I’m sure you know it, it’s a classic for that time.

ML: I sort of recognized them. I remember people were … I never had a pair.

BK: Maybe I’ll send you my design if you want a sneaker to wear.

Views of Bill Kouligas and Niklas Bildstein Zaar, “The Suspended Hour,” Capsule Plaza, Milan, as part of Salon del Mobile, 2025. Photos: Stefano Mattea

ML: This is a good place to get into it. I did something with Supreme a couple of years ago. They called it a collab, but it wasn’t, really. I mean, I didn’t put anything creatively into it – they designed it in-house. They were great to work with, but they just wanted to use imagery that I’d already made, especially from Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore [1999]. Before that, I also did something with Bottega Veneta [at Horst Arts and Music Festival]. I’ve found myself getting more and more involved in fashion and brands. Essentially, because that’s the only place where there’s really any money left.

BK: The Nike thing was interesting, to be honest, because we did work creatively on the sneaker. We used the existing silhouette, which has a very identifiable sole and an architecture that all the panels are based on. But we changed everything, from the materials to adding new applications and even modding the Nike swoosh. We used it in a much subtler and, in my opinion, more interesting way.

They have a huge development team that can bring anything you can imagine to life. I would be talking about a painting by Lucio Fontana that uses a lot of handcraft, and we’d try to translate it into the design language of a sneaker product. Who would have thought that one of his ideas would make it onto thousands of kids’ feet? It was a great learning curve in that way, thinking about how curiosities of mine in art or mythological history could be utilized as design principles and somehow enjoy a very different afterlife.

ML: You’re going to them with this esoteric knowledge, these arcanae that lie outside of their experience or their training or whatever. That’s the exchange, the economy of it, isn’t it? It’s very strange for me because I was thirteen when punk kicked off, and I was very much indoctrinated in not selling out. And even though punk was very resistant to or even despised the hippies, when I step back from it now, I see there’s very much a continuation of that countercultural resistance against corporate interest. And I just sort of marvel at the span of my own existence, that I got to experience a mindset that’s almost become antithetical now. Do you know what I mean?

Mark Leckey / Supreme, Hardcore Patchwork Harrington Jacket, 2023. Courtesy: Supreme

BK: Absolutely. To come from that and wind up working with a corporation, channeling that energy …

ML: But it doesn’t feel like selling out. For one, it’s necessary. And in terms of an exchange, maybe it is legitimate. I don’t feel compromised by it, because it’s about trying to position yourself in something that, to me, feels quite new. I haven’t really got any tools to understand it, because it seems so unexpected. Five or six years ago, one of the big problems in the art world was how rapacious the art market was and how it would just devour anything and everything. And now that conversation is kind of gone. So, I’m finding myself having to adapt very quickly and very nimbly. You’re always in a dance, but now, it’s become much more explicit.

BK: The seventies and the early eighties were a very different reality, socially and politically. There was a lot of room for resistance. And while it will always be necessary to antagonize the system in order to create, I think the way we behave now needs to be a little more coherent with how people perceive information. I got obsessed with music at a time when records were the most accessible medium for me to understand philosophy, poetry, photography, art, all packed into one thing. They opened up a whole universe. Records are not that medium anymore. But if one hundred thousand kids get introduced to your work through a Supreme collab, why couldn’t that create a gateway for them to understand the world more sincerely?

ML: I don’t know if that’s my approach, actually. I’m not interested in distributing information, but in opening up spaces of imagination and possibility through esoteric knowledge. For me, that just means a non-academic, autodidactic pathway to gnosis, or grasping the world as it is, which I learned initially through music, then through art. In a way, I think there’s enough of them already; but politically, it’s interesting because I think the media continue as if these things can be reasoned out, if only you speak enough truth to power. But the right are using magic. And I think the left have to bind some kind of esoteric spells to resist the power the right has accrued.

I got obsessed with music at a time when records were the most accessible medium for me to understand philosophy, poetry, photography, art, all packed into one thing. They opened up a whole universe.

BK: I read quite a bit about your show in Paris [at Lafayette Anticipations] before I went. I’m curious how you put it together and how you utilized gnosis as a guide there.

ML: Like I’m saying, I’m not looking for you to learn or find something of interest that can be unpacked and can lead you to information about technology or media. It’s trying to make something psychedelic, something that you experience and that actually stops you thinking, or that’s just pure affect.

BK: Do you think it’s some higher sense of consciousness, or the opposite?

ML: I don’t know. Maybe something dumber and more animalistic, in the sense that you just feel it in your body, on this nonconscious or somatic level. I talk a lot about music at the moment. Music is a condition that I aspire to, that I can move towards, in the sense that it doesn’t make me think. My first experience is to be moved or excited or to want to dance. And then I can analyze it and maybe become interested in its meaning and its signification or whatever. But initially, I just want it to do something to me. That’s what I’m going for.

BK: Are you using sound at the show?

ML: It’s a huge part of it, yeah. I got very interested in medieval metaphysics, and was reading a book called The Saturated Sensorium [by Hans Henrik Lohfert Jørgensen, 2015]. It’s about the medieval church: You’d have icons, but there’d also be incense and chanting, and you could touch the relics, you could kiss them. All your senses were activated. That’s the kind of approach I was going for, to be in this sensorium that’s just acting upon you.

BK: That’s very interesting because it also changes the perspectives on what is the piece, what is the experience, what is your perception within the space, what is your emotional response. And then you get lost halfway through, in this higher state of, let’s say, euphoria.

ML: Euphoria and melancholy at the same time. That’s not what I intend, but that’s how it always comes out.

BK: It’s this up or down feeling.

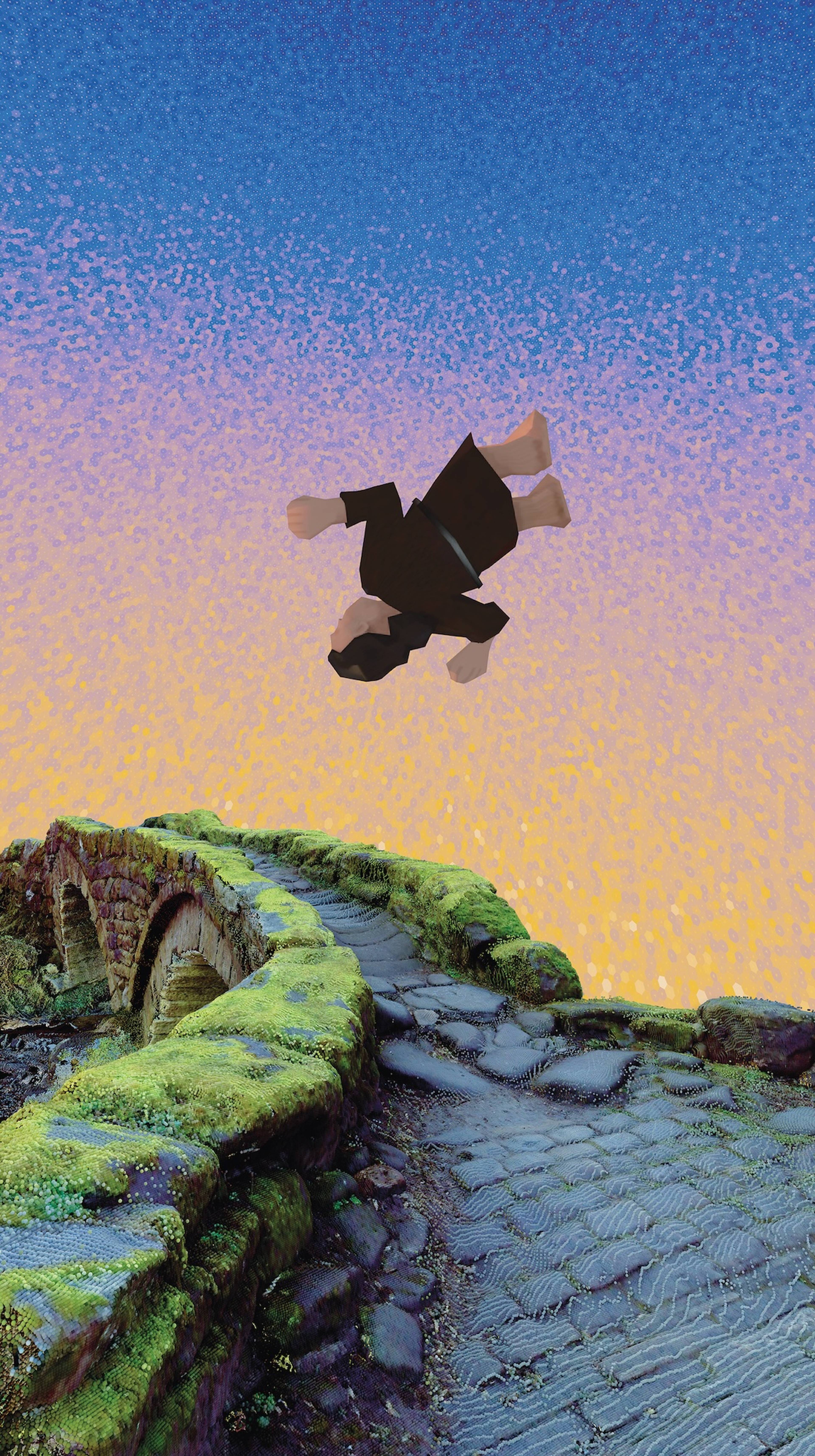

Mark Leckey, Taken-Out of the Place-You-Stand, 2024, archival pigment print on Canson Edition Etching Rag, 104 x 58 cm (image), 106 x 60 cm (paper).

Spike Edition of 35 + 5 AP, numbered and signed on the back

ML: There’s a sort of wave, or two waves meeting each other.

Someone the other day was talking about how they’re very particular to themusic of the North of England, where I’m from. Bands like Joy Division, they operate on that emotional level, either euphoria or melancholy or weirdly managing to combine both at the same time. At this point, I think it’s become a kind of IP of these derelict places, but it’s also the scene I got into when I was thirteen, fourteen, living near Liverpool. It was irresistible in some ways. But how about you, where were you?

BK: I was born and raised in Athens. There was very much an underground culture, but obviously not in the same way as in the UK. We were always looking at those things from afar – television played such a big role in how we perceived music, and magazines, too. I got into record-digging, just starting from whatever was popular, really famous rock bands, and then slowly started nerding out, going every weekend to the flea market. The whole visual art side of vinyl created such an interesting magnitude for me to discover things I didn’t know. I bought a lot of stuff naively, just because I liked the look of it. I didn’t stick to one genre or one scene, partly because I had very little in the way of examples – you would only get to see the bands big enough to make it all the way to Greece, when they were really established, unlike where you’re from, where you could go to the pub and see the first gig of whichever band ended up becoming a huge deal. So, moving to London when I was eighteen was very eye-opening. I could find any artist I’d ever heard of, and was performing music myself by that point, playing drums in bands and messing around with electronics.

ML: What year is this?

BK: 2002.

Music is a condition that I aspire to, that I can move towards, in the sense that it doesn’t make me think. My first experience is to be moved or excited or to want to dance.

ML: What kind of bands would you play with?

BK: It was a lot of post-punk revival, plus experimental music of all kinds. That world was taking cues from a lot of eighties music, like Throbbing Gristle and Cabaret Voltaire, but also industrial and early electronic influences, and mixed with academic composition, musique concrete, contemporary classical stuff. It was very punk in its own way, all these twenty-year-olds taking these examples and expressing them very intuitively, without really having any direction. It was similar for me when I started DJing. I was already into electronic music in the nineties, house and techno and drum and bass. But I had more of an approach than a sound, strictly speaking, which allowed me a lot of freedom to create new dialogues from contrasts, rather than just following a genre’s rules.

The really formative thing that was happening in club music was the infusion of the so-called “global” sound, from Africa, South America, their diasporas – productions that were radically new to my ear. Club culture was much more structured before, with very different crowds going to x, y, z places. And suddenly, the role of a DJ became more like that of an architect, to think around a space and lay out all these sounds in a way that opened a new world for a lot of different audiences to come together, people of all generations, races, sexual orientations.

A lot of these things have been normalized now, but at the time, it just felt like a very vital moment and a very, I don’t know, severe energy that was important for me thinking through the label. Not only curatorially speaking, but also around who we would involve. Rather than a formula, PAN became a bit of an open platform for people to just keep expanding their creative sensibilities. A lot of things have failed. But a lot of things have also opened up new doors. We broke the arts through a club infrastructure, we brought the club to art spaces. It’s some animalistic type of way to not really think and just keep moving.

ML: When I came to London and made Fiorucci, that got absorbed into this whole idea of hauntology and Mark Fisher’s arguments about the slow cancellation of the future [a term coined in philosopher Franco “Bifo” Berardi’s 2011 book After the Future]. That’s something I’ve always struggled with. Looking back now, there’s a moment of transition, where the genres that I grew up with in the late 20th century kind of collapse or dissolve in the early 2000s. But as you’re saying, it feels to me that the condition of music now is that it’s moving across. It’s expanding through space rather than time, and not so much looking for the next thing. And this has been one of my disappointments in the art world. I thought art would mirror that or adopt the same kind of pluralism or open itself up to this – hybridization isn’t the right word, but to a condition where things are less bounded. But the art world insists on seeing things in a very linear and prescribed way. And I think that’s why I’ve turned back to music.

BK: I’ve been thinking a lot lately about the role of liminal space. What is the space between stuff, what is artistic output within all these worlds, what thresholds can it somehow occupy? Because we have open-source everything, basically. People can use any sort of information or knowledge or software or tools to create anything they want. Where I find myself is potentially pulling all these different strings and having this flowy narration through these worlds, without being literal or didactic about how you should feel.

I also like what you said before about music. When you look at a painting, besides the aesthetic point of view, whether you like the result or not, you need to have a set of knowledge in order to understand.

ML: Just to approach it, even.

BK: Whereas with music, you can go to a mountain in Tibet and sing to someone, and they will respond to you right away. You don’t even speak the same language, but they understand you. And in the same, let’s say, abstract way, I’m grappling with how you can actually be everywhere without necessarily specifying what’s what, just utilizing whatever’s interesting to you, and to be free in that.

Dissonance, its compositional behavior, have become so palatable through popular culture that they’re not even avant garde anymore.

ML: I also wanted to talk about the first time we met, with Florian Hecker at Southbank, right?

BK: The very first time was the premiere of your responsive collaboration with him in 2011, at the Tate Modern.

ML: That’s right.

BK: And then we did Southbank.

ML: For a PAN showcase?

BK: Yes. Thirteen years ago.

ML: So it’s basically an audience who came for a night of PAN. And it’s, you know, experimental music. I wouldn’t say difficult music, but as you’ve described, it’s trying to open things up. And I remember Florian coming on, and I was sitting next to him, and people just getting up and leaving. Do you remember that?

BK: I remember. He likes to challenge people.

ML: One, I didn’t think those boundaries existed anymore. And two, I thought that the audience would want to stay within them, but they didn’t. It was amazing. I love that.

BK: It’s a long time ago, but I feel music has changed so much that it wouldn’t perform the same way today.

ML: What do you mean by that?

BK: I think there’s such a different sonic understanding, if I can call it that. People would be a lot more receptive.

ML: Right. We’ve been talking around it, that music has very much moved away from melody or rhythm.

BK: There’s an ongoing conversation about how much even mainstream music has been using this palette – maybe not Florian Hecker’s palette, but let’s call it challenging music – in a more structured way. Dissonance, its compositional behavior, have become so palatable through popular culture that they’re not even avant garde anymore.

ML: I really notice it in film scores. They’re so much more abrasive now, versus something like the strings in Star Wars [1977–83].

BK: Which is funny because a lot of the younger generation of club producers grew up with video games, and they heavily involve sound design in their work. Whereas before, 808s and synths made for much more linear productions. So, cinema has influenced contemporary music, but also contemporary music has taken over the cinema.

ML: Definitely. A lot of music I’ve been listening to recently is also less like production than like its artifacts, or its reassembled byproducts.

The idea that waste still gets utilized or alchemically converted is part of what music is in a way, isn’t it? It’s the conversion of surplus into an energy, into this kind of spiritualizing matter.

BK: You know, when you convert a WAV file, which is the full-fledged range of frequencies when you produce a music track, into an MP3, the converter reduces so much information to just the very basic audible signals that it requires for the track to make sense. I always wonder what the reverse would be. You’d end up only listening to, let’s say, the waste of frequency.

ML: Waste, exactly. I like that a lot.

BK: I need to find someone to build that converter for me. I think it could be interesting.

ML: That fits with something else I’ve been thinking about recently, about how the subcultures of the past were basically byproducts. They kind of transformed the inefficiencies of the postwar era into pop culture, into rock or whatever. And that’s another important change, that everything has become much more frictionless. There are no longer these gaps, these broken spaces you can convert into something productive. But the idea that waste still gets utilized or alchemically converted is part of what music is in a way, isn’t it? It’s the conversion of surplus into an energy, into this kind of spiritualizing matter.

BK: Yes. Couldn’t be better put, to be honest.

ML: I like that. That’s fine. That’s what I get excited about.

Paris, 2025. © Rafik Greiss

___

Mark Leckey’s 2025 edition for Spike, Taken-Out of the Place-You-Stand, is available for purchase in our online shop.

Mark & Bill will both DJ at an afterparty for “Enter Thru Medeival Wounds” at OHM Berlin on Wednesday, 10 September.

Mark Leckey

“Enter Thru Medieval Wounds”

Julia Stoschek Foundation, Berlin

11 Sep 2025 – 3 May 2026