Monica Bonvicini’s 2004 interview with Jennifer Allen about the relationship between architecture and sexuality is a blueprint for her 2022 exhibition “I do You” at Berlin’s Neue Nationalgalerie.

Jennifer Allen: What is a building for you?

Monica Bonvicini: A building is a container, something that acts as a barrier and stays in your way. Actually, it would be nice not to have any buildings. When I walk down the street at night and look into the apartments with the cozy lights on inside, a feeling of disgust hits me. Of course, one cannot live without buildings. And disgust is a very personal reaction. At the same time, a building stands for a culture, a time, a style – for power … I don’t like buildings in general. Architecture is different. Architecture is more like a theoretical object, a theory with several points of entry.

Sexuality seems to be a point of entry in your approach to architecture, whether one considers the early work Wallfuckin’ (1995/96), where a woman rubs herself against a wall, or Pavilion (2002), which puts an S&M seat into a frame that matches the size of Le Corbusier’s minimum living space.

I started working on sexuality for two reasons. First, ten years ago, I was reading a lot of gender-related theory about architecture – like Beatrix Colomina’s Space and Sexuality , Leslie Kane Weisman’s Discrimination by Design , Aaron Betsky’s Building Sex . Second, I was interested in dealing with stereotypes in the fields of both gender and architecture. For example, a construction worker is a stereotypical figure in terms of masculinity and in relation to the building site, which ends up producing architectural history. Also to be a man – whether working on the building or in it – is to be a figure that is taken for granted but: when is a man a man? I tried to get at these complexities with works like What Does Your Wife/Girlfriend Think of Your Rough and Dry Hands? (1999), which included a survey of construction workers. Beyond these stereotypes, sexuality is something everyone knows. It’s an easy, fundamental need, like architecture itself. You have something under your belt and something over your head. And you need both.

Monica Bonvicini, Black, 2002, galvanized steel tubes, leather strings, swing, metal chain, spots, black walls, and black linoleum, dimensions variable. Photo: Willy Grauby

You seem to adopt a Freudian approach to built space: Does all architecture have to do with sexuality?

Yes and no. Every space has a character that makes each person react in a different way. I am sensitive about the way spaces create these kinds of reactions. Everyone can make the associations they can make … For me, sexuality is a way to express ironically and recklessly what I want to say about issues that I might not be able to talk about in another way. There is something basic, and still very complex, in sexuality that I found in architecture, too. Wallfuckin’ or The Fetishism of Commodities (2002), are installations that deal with sexuality, yet they do so with an “I don’t give a fuck” attitude towards big structures like theory and architecture. With its metal, chains and leather, The Fetishism of Commodities confronts Marx’s ideas about labor with architects’ fetishism for pure materials and an S&M sexuality, which is about power relations. Since you mentioned Freud, everybody has a sexual drive; sexuality is with you all the time, however it is expressed. That said, I don’t want to put buildings on a couch. Along with reading, I analyze a work to decide what is more important and what is not as an art work. But if you deal with sculpture and large-scale installation, then you have to relate to the body first, and sexuality is part of it.

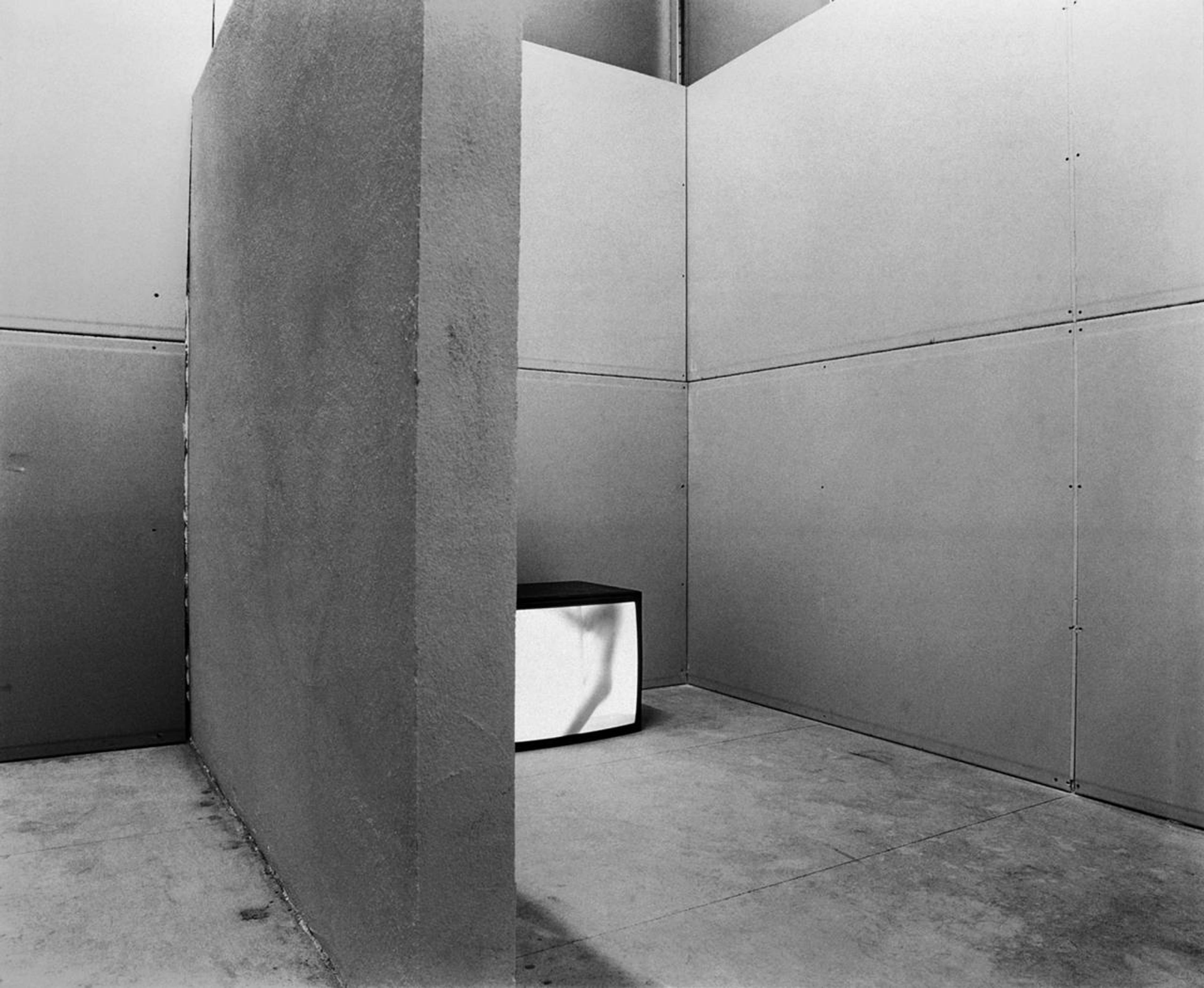

Monica Bonvicini, Wallfuckin’, 1995/96, b/w video on monitor, sound, amplifier, speakers, drywall panels, aluminum studs, bricks and mortar, white paint, wood panels, and door, 250 x 310 x 330 cm, video: 48 min.

Whose body?

Bodies, my body, the viewer’s body. Since I’m working with space, I can’t avoid dealing with the body of the person who moves through the installation. In sculpture, the proportion of the human body is a parameter that defines certain relations. I like the idea of the viewer being active with the work, even to the point of making it or destroying it. The moment you do things, you realize them better than when you are looking at something and trying to understand it. I am interested in involving people because, as an artist, I also want something back instead of just presenting a piece in a gallery. I want people to be able to do something with my work, and I want to see what they do with it. With Plastered (1998) – a gyprock floor that crumbled when you walked on it – it was funny to see how people reacted to the work, which almost produced a performance-like situation. Black (2002), which consisted of a dark, sacral, fenced-in space with chains and leather, functioned similarly, even if at a different level. Viewers were able to use it, and, at the same time, since the piece was more staged, once they found themselves inside, they were forced to be aware of their movements: not everyone likes to show others how much fun it is – or not – to lie on an S&M-looking leather swing… Some did not trust themselves to walk under the spotlight, probably because they liked to look at the work, at the stage, but weren’t sure they wanted to be part of it, acting in it. BEDTIMESQUARE (1999), was a piece that anyone can use: just cross over the cold and clean white ceramic tiles and lie down on the mattress. Due to the materials and the way this work and others were presented, it’s not always clear to people that they can use it, even if they recognize everything: mattress, light, leather, swing. You think you recognize it, which means you think you know what you are seeing, but you actually don’t.

Architects often quote art works, their aesthetic and form; artists dealing with architecture are more interested in the idea and the possibility of architecture, not in its materiality or size.

You seem to create a fluid, living architecture where the walls are “built” by the viewer.

Yes and no. I am interested in creating a space or situations that are very precise and determined, to present a philosophical as well as a physical structure where you can act. Normally, people have a lot of respect for art, and, in some ways, I want to demystify the aura that is still around it, despite all the attempts that have been made to break it. At the same time, I think art is there to think, to make connections you wouldn’t have thought of otherwise… “What you see is what you see,” but what do you see? In terms of architecture’s aura, let’s take glass and the connected idea of transparency and, with it, democracy. Broken glass has become a recurrent material in my recent work, although I am the one doing the breaking – and for the record, I don’t shoot at the glass with a gun to make cracks and holes, as has been reported; I smash them with a hammer! Stonewall (2001), was the first piece that incorporated broken glass. I did it shortly after the riots during the G8 summit at Genoa, which was gated off to the public. I was also thinking about Cady Noland’s gates and public architecture with its accessibility and its monumentality as a State-related power symbol. I wanted to show that even if you have a gate in front of you, that doesn’t mean that you can’t do something with it or something to change it. Stairway to Hell (2003), was my work for the last Istanbul biennial: a glass pavilion set at the top of a free-standing staircase, which was supported and enclosed by chains. When people walked up the stairs through the chains and saw the glass above, they may have thought about transparency or freedom. But since the glass was broken, viewers couldn’t clearly see the whole space on the upper floor surrounding the staircase, nor the art works hanging there. The whole experience of walking up the stairs was sort of disturbing.

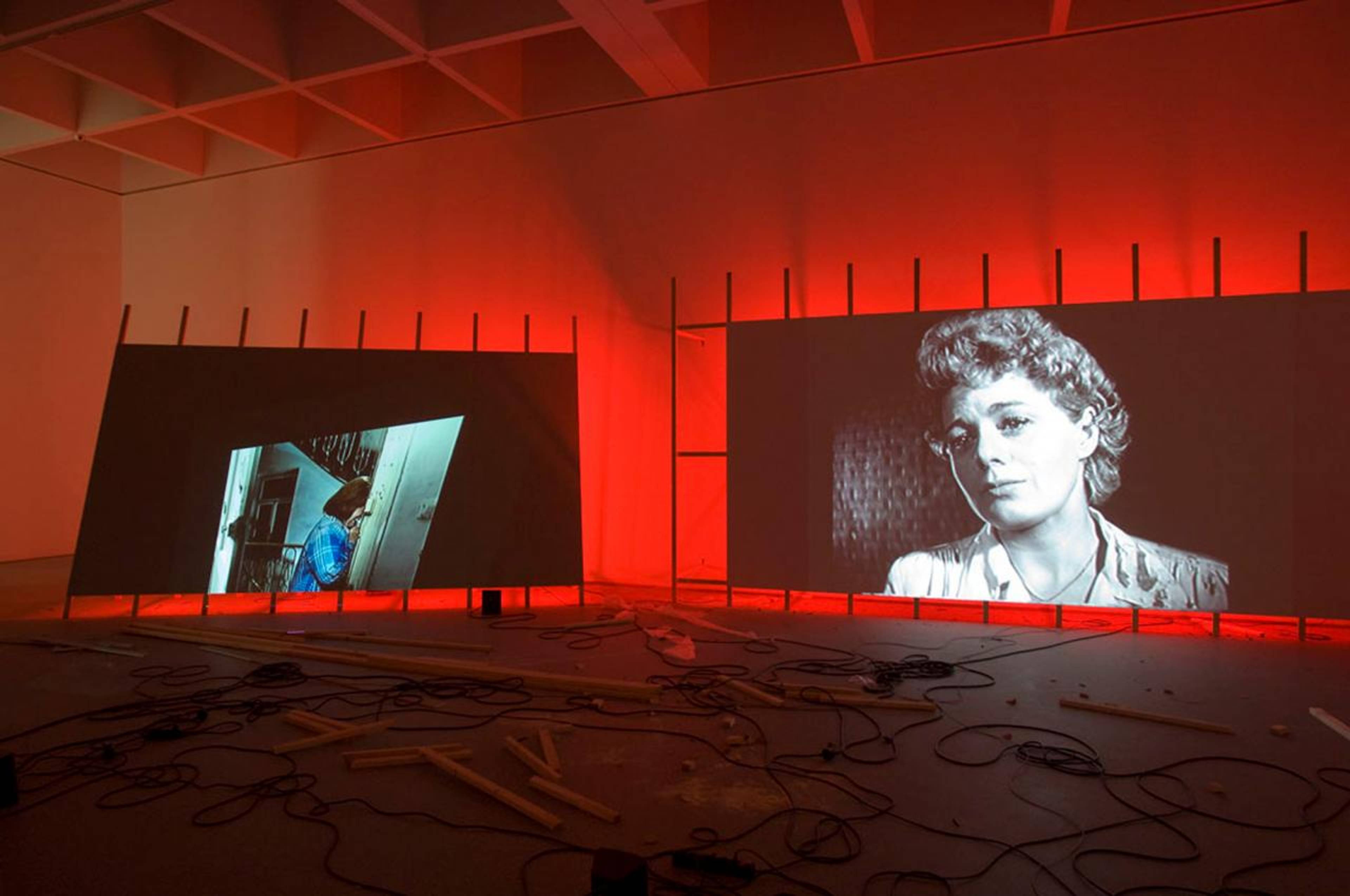

Monica Bonvicini, Destroy She Said, 1998, two video projections (each 60 min.), wood structure, white paint, and plasterboard, dimensions variable

What role does site play for you? Do you refer to the building’s actual use – for example, the staircase in the biennial art exhibition – or to the building’s history? And how do these elements mix with your interest in theoretical writings, from Freud to Bernard Tschumi, and in fetishized signature materials, like Mies van der Rohe’s or Dan Graham’s glass?

I am more and more suspicious about dealing directly with a site. Sometimes curators seemed to be using artists to make an atmosphere of meaning around the site. But if artists have only two weeks, then they can’t do so much about the identity and history of the building. If I have a show in a place where I have not been before, I always want to go there before I even start thinking about the work I will develop for that place. I like to see the building, the neighborhood, to see the show they did before… But my relation to history does not tend to begin with the building where my work will appear but with a theoretical dimension. Theory is abstract, yet it has been realized in buildings, regardless of their location. Instead of addressing the history of a particular building, I try to get at the ubiquity of modern architecture through theory, be it architectural or philosophical. The actual building functions less as a specific site and more like a set of possibilities and materials for the work and for the viewers. If I think about my early video works, they were all installations; you had the architecture presented in a three-dimensional way, and the body of a performer acting in the same space that was also reproduced on the video screen. In recent video works, like Shotgun (2003), I left the filmed urban architecture, being the rotten body of a capitalistic system based on ideas of success and moneymaking but reduced literally to a sick body that needs to be repaired or cured. For Break it, fix it at the Vienna Seccession with Sam Durant last year, we began with two Wittgenstein quotes: “Try to break the border of language? Language is not a cage,” and “The attempt to break the walls of our cage is totally and absolutely hopeless.” We built the word CAGE within the space as a kind of maze, so people couldn’t get out of the structure. They could see only what we let them see through various openings in the installation: “the hanging sculpture” made of cut-up building models, a column in the building, its glass ceilings and, finally, the video where we destroy the word ANGST and then use the remains to build the word FEAR. If you already knew the space of the Secession, you would be able to recognize where you were; otherwise, you would be just sort of immersed in a sculpture, which means in a different space. In the end, you surely were in the building of the Secession, and that tautology was also something we tried to question in the video piece.

Monica Bonvicini, Stairway to Hell, 2003, steel stairs, chains, broken safety glass, metal frame, aluminium, and spotlight, 850 x 360 x 399 cm

Your resistance to site seems to critique both art and architecture, since architects often design in relation to site. How do the two practices come together for you, especially in light of the last decade, which saw architects and artists exchanging roles?

I find the works of artists doing architecture more interesting than the other way around. There’s constant conflict between the two professions since architects understand themselves as the biggest artists – maybe because they make big things. Artists are not under such financial and political pressure; they can deal with issues that architects don’t have the time nor the frame of mind to address. I have been working with architects, and I was at different symposiums on the relation between architecture and art. But I always have the feeling that even if the two fields are very close, artists and architects still speak two different languages… Architects often quote art works, their aesthetic and form; artists dealing with architecture are more interested in the idea and the possibility of architecture, not in its materiality or size. The good thing about being an artist is that you cannot hurt anybody; if the work is bad, you may add some stupidity to the general pre-existing stupidity (which is already bad enough). But architects, as we all know, can do damage that has a much longer life…

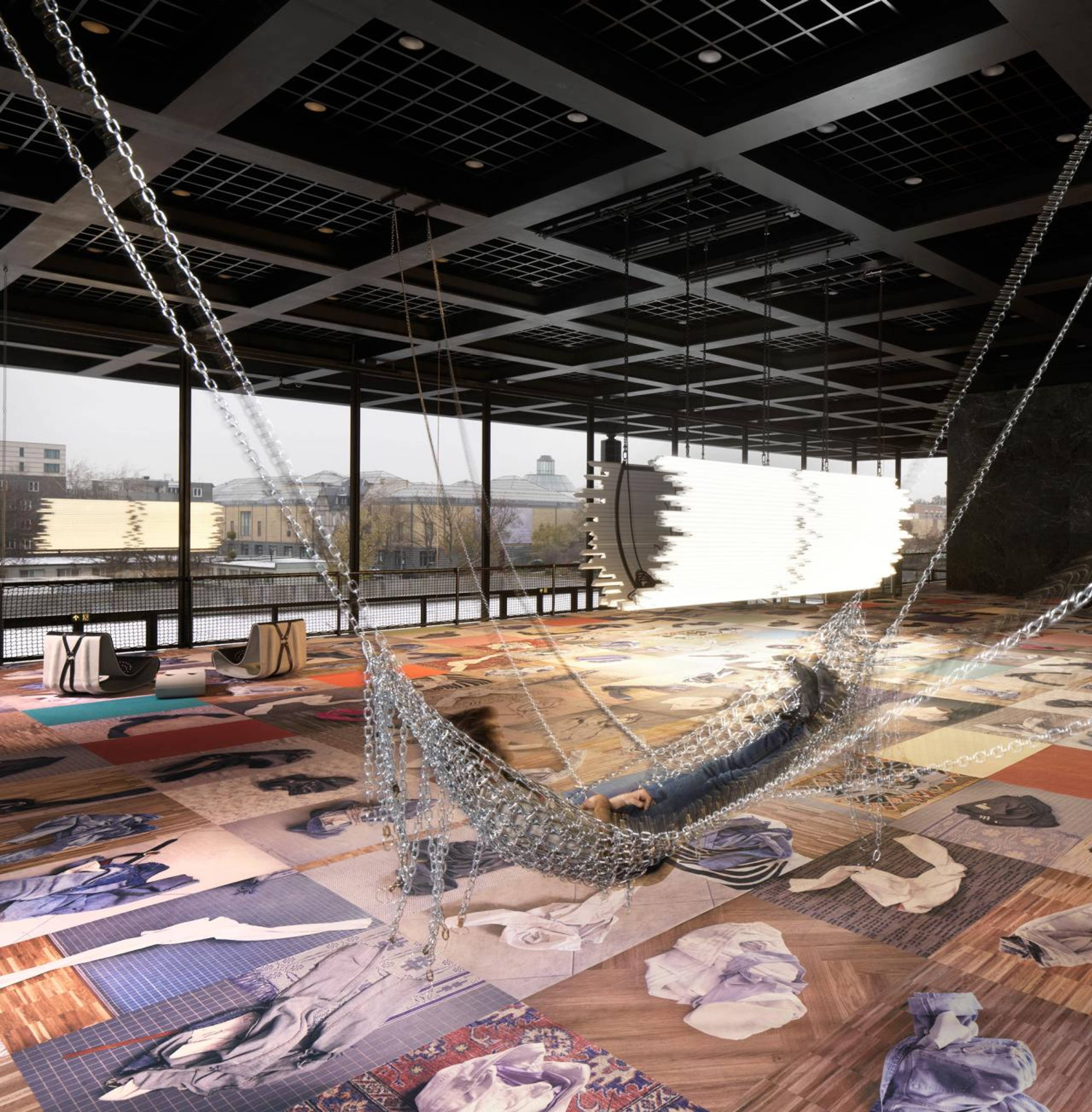

Monica Bonvicini, Breach of Decor, 2020–22. Installation view, Neue Nationalgalerie, Berlin, 2022

“I do You”

Neue Nationalgalerie, Berlin

25 Nov 22 – 30 Apr 23