An unwritten rule of LA life is to do anything to avoid crossing town. So it was strange to find myself commuting to Beverly Hills to catch multiple screenings at the charmingly shabby Lumiere Cinema. Eugene Kotlyarenko’s The Code (2024) is a pandemic mockumentary about surveillance and performativity wrapped in a screwball comedy while Peter Vack’s www.rachelormont.com (2024) is a vaudevillian, nightmarish tragicomedy about the chronically online. Both films premiered in LA last summer, both circle overlapping themes, and both feature actor Dasha Nekrasova – yes, of the Dimes Sqaure podcast Red Scare – as an updated femme fatale for the e-girl generation. Vack also stars opposite Nekrasova in The Code. Naturally, watching the films, I couldn’t help but think of them as something like mischievous evil twins, each visually and formally inventive in unique ways, but sharing a DNA similarly obsessed with capturing what it means to be a person in a world addicted to being online. I caught up with Kotlyarenko and Vack for a conversation, by turns complimentary and combative, about cinema, the internet, and why the directors bristle at the suggestion that their films are in any sort of conversation with each other.

Sammy Loren: Let’s start with your films from last year, both of which confront our hyper-online moment. I’m curious if you think we’re living in a moment of digital utopia or something more like a social-media nightmare.

Eugene Kotlyarenko: I don’t know. Inherently, human beings have a propensity to catastrophize. Every generation thinks they’re living at the end of history because it makes them feel relevant. I try to take a step back and find avenues for expression that feel completely unique to this moment, and let other people decide whether they’re dystopic or not.

Peter Vack: You can find moments of dystopia and utopia wherever you look. People characterize my movie as dystopian.

SL: How do you feel about it?

PV: How do I feel about it? I don’t know. It’s really for others to decide.

EK: Personally, I think your movie is dystopian, Peter.

SL: Do you think your films are critiquing internet culture or simply recreating it?

PV: I’m always confused by that question because I don’t go to the movies to get answers or a critique. I go to be entertained, to see something I’ve never seen before, to have fun with characters I find exciting. Eugene and I are both a little Letterboxd-pilled. We read all these reviews, and there’s this common refrain of, Well, what was this saying? What an impoverished way of going to the cinema, needing a movie to diagnose you or give you some prescription for your life.

Stills from The Code, 2024, dir. by Eugene Kotlyarenko, 98 min. Courtesy: Eugene Kotlyarenko

EK: People need time between the thing they’re analyzing and the present moment. So when art seems a little bit closer to reality, in terms of when it’s presented to the world and what it’s reflecting back, people are angry if it doesn’t offer a clear commentary. Most work about contemporary life that gets celebrated has a simplistic or prescriptive approach. When you’re analyzing things that haven’t been codified yet, viewers can get frustrated if the work doesn’t tell them how to behave.

PV: Now, let’s be clear. We’re talking about a subsection of viewers who get angry at movies that deal with elements of the present without clear morals.

EK: I don’t want to say it’s everybody, because I think there are people who like to be challenged. But I don’t think that’s the prevailing norm.

PV: Sammy and I are involved with readings, and say what you will about readings, but I think writers feel more permission to reflect the moment. You can write something in a week, and it comes out that week. On the other hand, as Eugene knows, the struggle with films is they’re so hard to get made. That’s why so few filmmakers have the courage to make work about the present. It’s easier to create something that will remind you of your favorite films from the 1970s and give the audience a buzz of nostalgia.

EK: What do you think, Sammy? You curate readings. Do you find that people there are more tuned into the freedom of the ephemeral in their expression?

SL: The magic of literature, in part, is that it’s cheap to create. Anyone can go to the library and write for free. But the flip side, at least in the readings Peter and I often are involved with is that people just vomit up whatever is going on in their life. There’s a lack of artistic rigor. Writing is not stress-tested in the same way films are, where you not only have to write a whole script, but to convince all these other people that it’s worth a lot of their money. Versus someone writing a poem on their Notes app on the way to a reading, making a film is like moving a mountain.

PV: I’m not making a statement about quality. I’m just saying that I see more people at least attempting to talk about their lives in the present in the lit world than in the film world.

Eugene, you’ve done this in your films, and I’ve at least attempted to in mine, even though they require all this rigorous crafting. That’s part of why I like readings, even if they’re less stress-tested – it’s the same with Instagram. Sometimes, they get at more truth just because people are not being precious.

So few filmmakers have the courage to make work about the present. It’s easier to create something that will remind you of your favorite films from the 1970s and give the audience a buzz of nostalgia.

EK: With some of my favorite writers, filmmakers, and visual artists, I might have a hard time defending the quality of any individual work, but they’re all super prolific. I really like prolific artists, and I respect – I don’t want to call it vomit or diarrhea – but let’s just call it, like, an embarrassment of …

PV: Riches?

EK: Of productivity. And that accumulates into a body of work where the whole is stronger than the individual parts. When you’ve experienced that whole, it’s way more powerful than a single masterpiece can be.

I would love to make a lot of movies before I kick the bucket, because I do think, especially when you’re interested in lots of different types of storytelling, that you’re not going to run out of ideas. So, the limiting factor is just how “professionally” you want to execute them. And then, I think what you were just talking about, Peter, that off-the-cuff, less-precious nature of expression, might yield something that is closer to, I don’t want to say perfection, but to the artist’s truth than something that has been worked on for a long time.

Stills from www.rachelormont.com, 2024, dir. by Peter Vack, 80 min. Courtesy: Peter Vack

SL: Peter, where do you fall on that spectrum of prolificacy?

PV: For somebody working only in film in the US, it’s become borderline impossible to be prolific in the way that directors from the 20th century seemed to be, for a lot of reasons. But I feel like, especially with content being what it is, if you’re an artist that isn’t always generating, you’re missing something of the flavor of what it means to be an artist now.

SL: What do you mean?

PV: The fact of having your phone in your hand, with X and Instagram and TikTok, demands some sort of athletic aesthetic. And so if you’re not rising to that, I think you’re missing something of what it means to be alive today.

SL: That’s something I’ve talked about with people in literary life. Some of the biggest writers do not use social media at all, like Zadie Smith, Maggie Nelson, and Sheila Heti and there’s a real magic that gets reflected back in the work. The thing is, even if someone makes a work that never mentions the internet, it’s still there, because it’s the air everyone breathes. As two artists confronting the internet, how do you feel about other artists somehow pretending it’s not there?

PV: I feel bad for them. I feel like it takes effort to not accept it.

EK: I feel like they intentionally cop out. They are proselytizing a rarefied form, you know? They’re pushing a medium that they care about towards irrelevancy because they can’t figure out how to express themselves in a mode that reflects day-to-day life.

PV: If I may interject, what you just said reminded me of something. I won’t name names, but this producer I know called me, and we got on the subject of the Cannes Film Festival. And he was like, Look, Cannes will never take your or Eugene’s movies. And I asked, Why? And he replied, It’s because they deal too much with the internet, and they [Cannes] don’t accept that it exists. And it just gave me such a sad feeling, because I feel like if you care about cinema – and Cannes clearly does – and you don’t want the internet to exist in cinema, then you’re cutting off the medium’s potential to evolve. It’s like you’re stopping the bloodline.

SL: Both your films play with transgression. How do you both think of that impulse?

EK: I’m just trying to make films that I don’t already see around and that feel entertaining and relevant to me, which is also how I assume other people will feel when they see my films – that’s my only motivation in making movies. Because I know from reading movie history, from watching many movies, and from helping other people make movies and making movies myself, that you cannot predict what people are going to like. If you think you have a formula, you are setting yourself up for failure.

Maybe we are after similar things, Peter, but I also think – not to put words in your mouth – you do prioritize the act of provocation

PV: I feel we’re not so dissimilar, but it’s true that I want to feel provoked. I saw Enter the Void in 2009 [directed by Gaspar Noé], and I really hated it. I thought of it in terms that I don’t even think of anymore. I was like, That was a mean-spirited movie, that movie was aggressive. But then it stuck with me in a way other films haven’t. And later, I realized that that feeling was what I wanted from a film.

EK: I think we do have the same impulse. We just like different types of movies.

They [certain literary writers] are pushing a medium that they care about towards irrelevancy because they can’t figure out how to express themselves in a mode that reflects day-to-day life.

PV: Eugene and I both have these experiences of helping others – Eugene’s also a producer, and I make a lot of movies as an actor – and then working on our own thing. As an actor, I am so used to the experience of watching filmmakers hold back, avoid certain material, avoid certain realities. When I get to my own work, it’s almost like I have all this pent-up desire and aggression, and I just want to go in the opposite direction of what I see happen as an actor.

EK: I want to clarify one thing: I operate under the belief that the movies I’m making can be enjoyed by a huge amount of people, and that is my only rubric for understanding what is good. And I guess my naiveté is believing that something good and entertaining and not boring, which does something new, will translate into success.

SL: You two have made very distinct films, but you’ve also collaborated. What is it like working in conversation with one another?

EK: I don’t agree with that assessment. I don’t feel like I’m in conversation with any filmmakers, really.

PV: I agree. I really love your movies, Eugene, because they get at this thing that I’m hoping to get at as well. But when I think of who I’m in conversation with, it’s not contemporary filmmakers; it’s online content, some net artists.

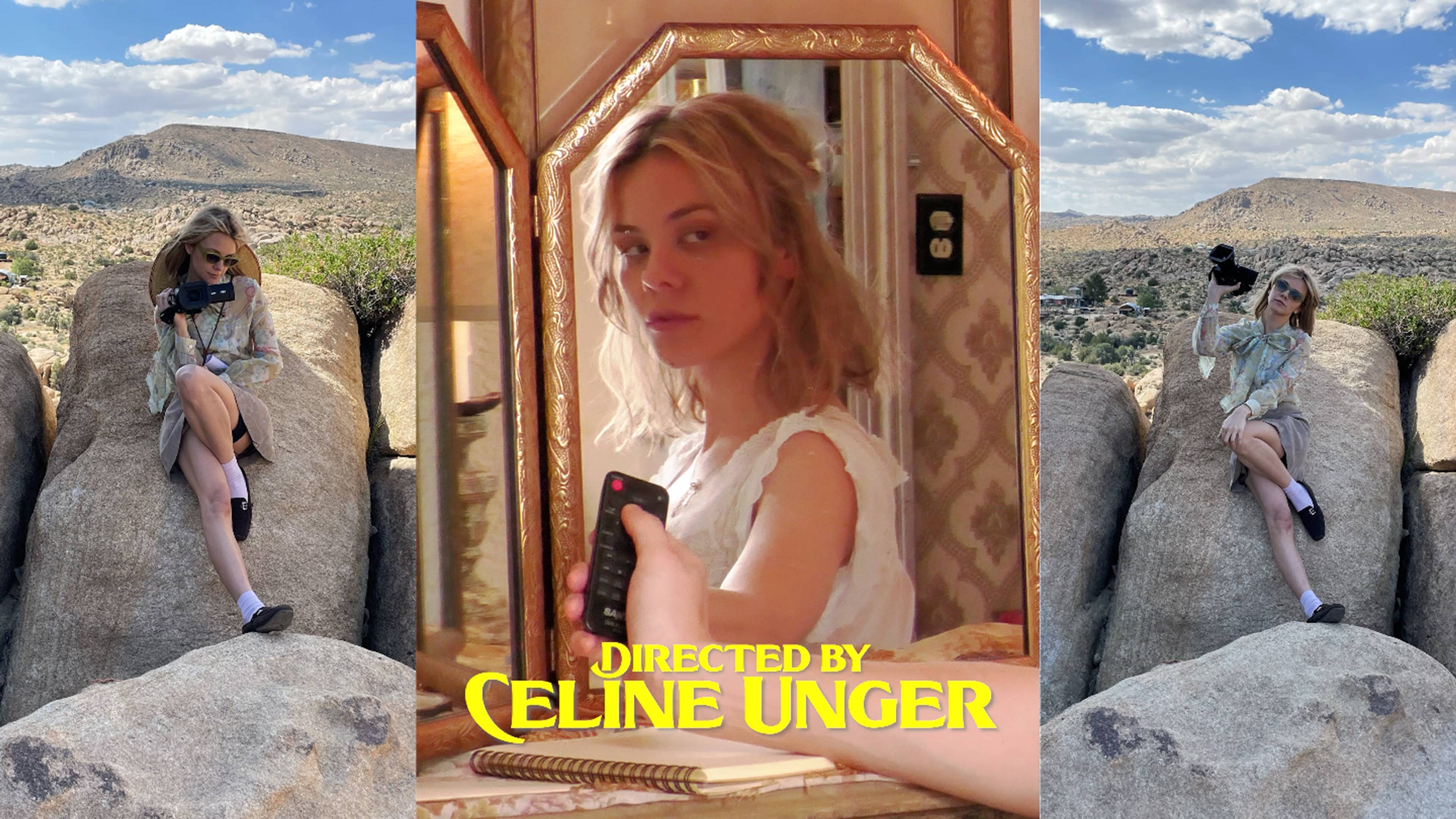

Dasha Nekrasova in The Code

Dasha Nekrasova in www.rachelormont.com

EK: I like Éric Rohmer, Robert Altman, stuff like that. But almost all the contemporary films I like are extremely backwards-looking and disengaged from things that I care about in contemporary life. So, it’s like, Well, that was cool, but it has nothing to do with what I’m up to.

SL: Eugene and I have lived in LA for many years. Peter, you’re a New Yorker. Do you see a divergence in artistic sensibility between those cities? I see it in the literary world immensely, but I’m curious if it’s in the cinematic world, too.

EK: When you talk about cinema world in LA, are you talking about Hollywood? I don’t really have a community here in LA. I also don’t really believe in scenes. Obviously, people who have the same struggles and the same desires and obsessions gravitate towards each other, but I tend to view every meaningful artist as their own artist.

PV: If you were somebody who’s inclined to see artists in scenes, you could say Eugene and I are part of the same filmmaking scene, and you’d put Betsey Brown in there, you might even put Louise Weard in there, and Jon Rafman, too, because we’re making movies that are finding an audience in an organic, grassroots way. Which might be because we are making movies that look at the way we live now and not, like, putting our heads in the sand in response to issues of being online. Eugene, your aversion to scenes is about taste, and I get that. But I don’t love or hate them. I just see them as a reality.

SL: What do you think about the tendency these days to clump people in scenes?

PV: Maybe it’s a reaction to the atomization of social media, where everyone’s forced to be an individual. Whether you like it or not, Eugene, people forming scenes is definitely the way the public is reacting to artists right now.

I feel like if you care about cinema – and Cannes clearly does – and you don’t want the internet to exist in cinema, then you’re cutting off the medium’s potential to evolve. It’s like you’re stopping the bloodline.

EK: We live in a tribal culture for sure, but I also think that, historically, literary and art criticism have always played significant roles in artistic milieus, from Dada to Pop Art. It’s nothing new; it’s just lazy. I love Pop. I love Andy Warhol and Robert Rauschenberg. And to me, they’re extremely different artists, with completely different interests, dealing with the world in different ways. I don’t group them together because some fucking critic grouped them together for me. I don’t group Werner Herzog and Rainer Werner Fassbender and Wim Wenders together because they’re part of something called New German Cinema. They’re different filmmakers with different interests.

PV: It still makes sense to me that it’s happening now because so many people view themselves as critics. We’re a whole society of critics.

SL: Even if your two films are not particularly similar, they overlap in interesting ways, as attempts at formally recreating the experience of being online. Peter, you also starred in The Code, and Dasha Nekrasova has a big role in both films.

PV: For the record, I’m honored to be considered in conversation with The Code. I’m a huge fan of Eugene, even before I was a friend of his. So it’s very meaningful to have my work be seen in conversation with him.

EK: Love you, Peter. One thing we do share is that Peter and I both enjoy playing devil’s advocate. You’re making assertions and assumptions about us, and even if your assumptions are correct, we’re both going to push back.

SL: I don’t have any other questions. Are there any last words you wanted to get in?

EK: I love Spike Art Magazine.

PV: Spike Art Magazine is just Page 6 for scenesters.

Spike Art Magazine is just The Drunken Canal for Eugene truthers.

Spike Art Magazine is On The Rag for r-word, vulgar cineasts.

___

The Code is streaming in some countries on MUBI. www.rachelormont.com is playing in ten US cities at the Alamo Drafthouse 17–21 October 2025. Eugene Kotlyarenko’s first feature film, 0s & 1s (2011), is now available on blu-ray from Vinegar Syndrome.