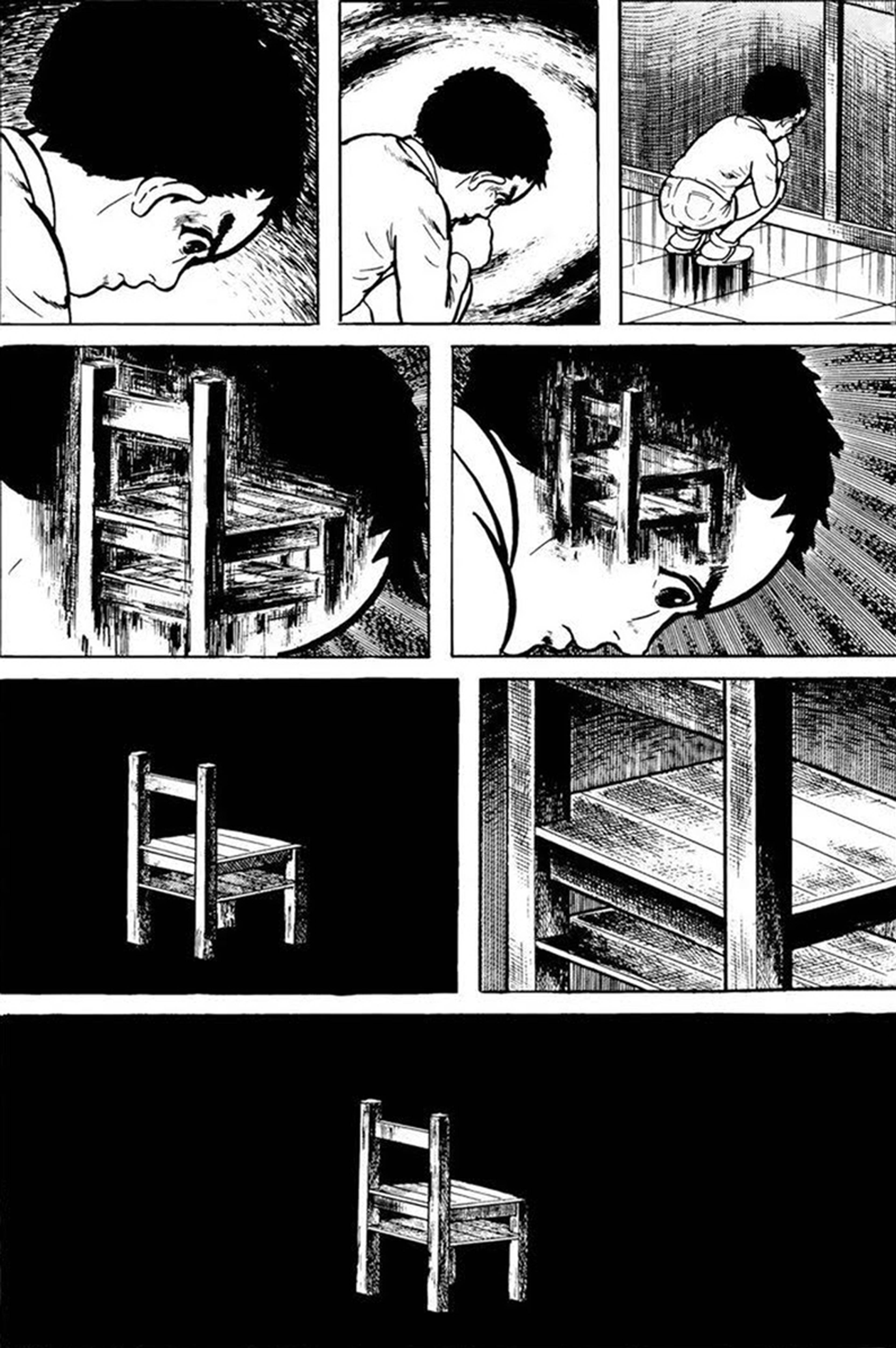

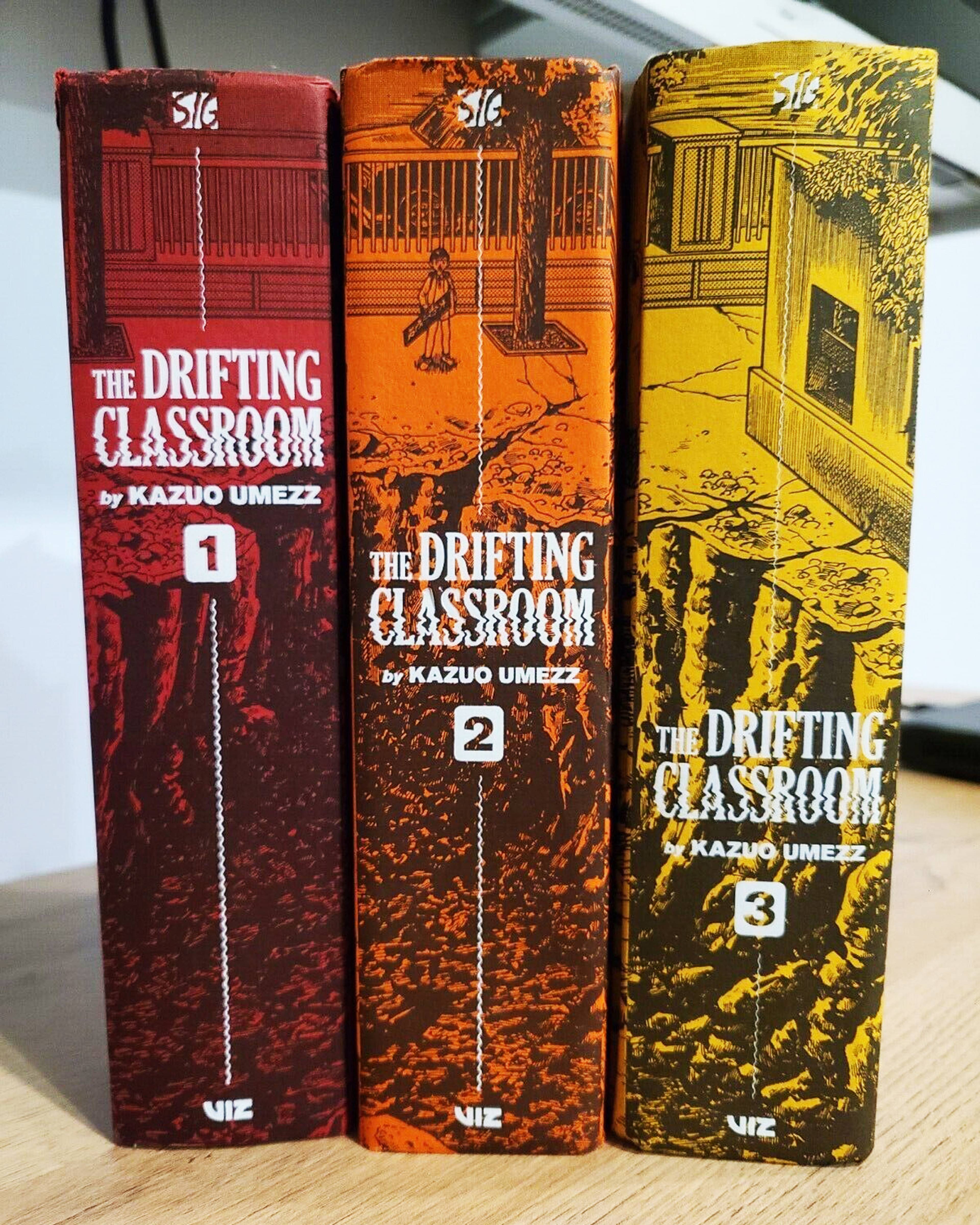

Kazuo Umezu, The Drifting Classroom (Viz Media, 1972–74)

A school explodes and gets teleported into a post-apocalyptic future hellscape. Terrible scant survival, terrible scenes of horror, and, meanwhile, in the present, a mother tries to help her time-stranded son in the future by secreting medicine in the yet-to-be mummified corpse of a baseball player. They communicate across time via a psychic eleven-year-old. The exploded body parts of a thief are teleported into the future, too, and they eventually save the day. It’s massively anxiety-inducing and incredible.

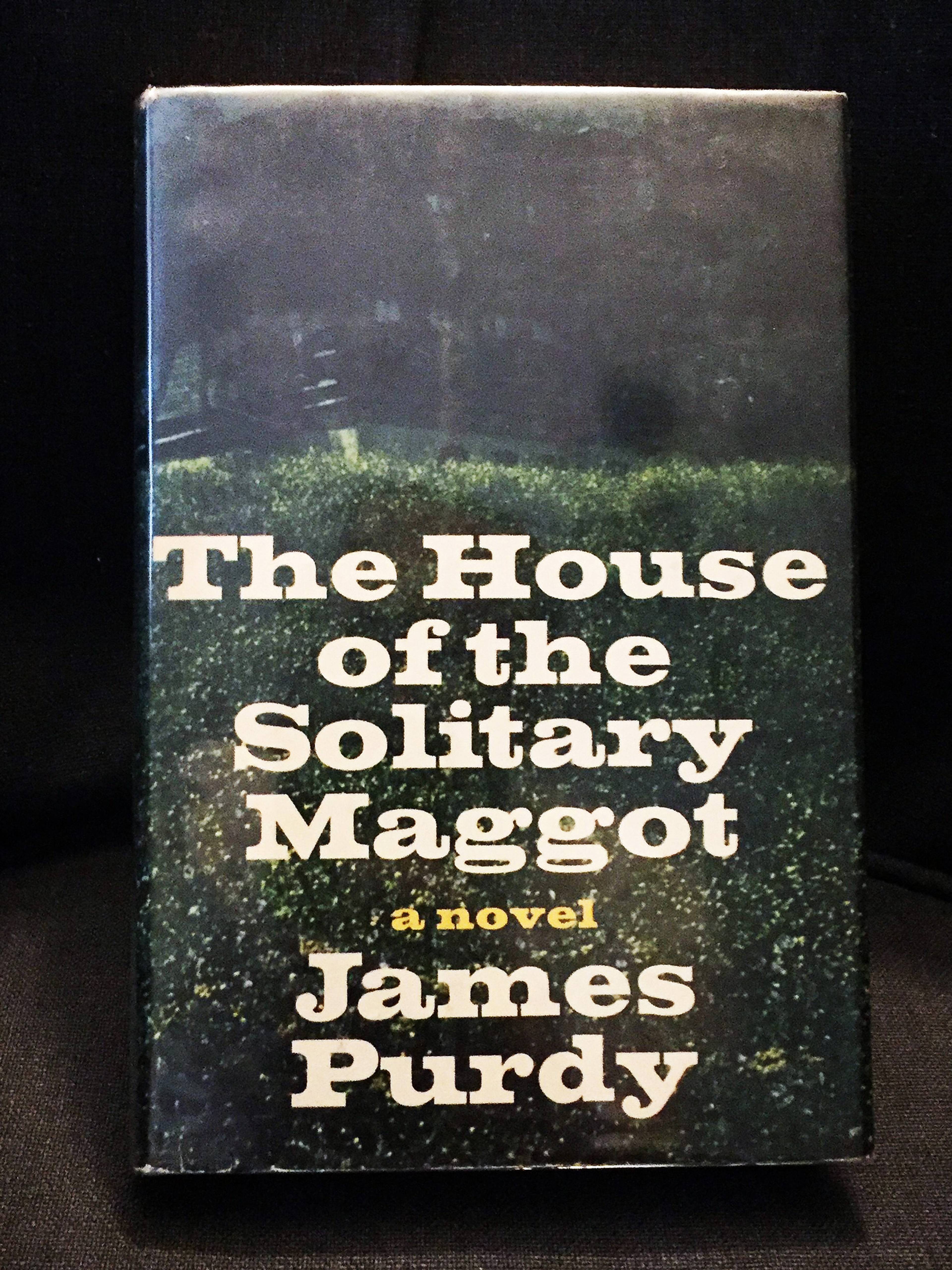

James Purdy, The House of the Solitary Maggot (Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 1974)

A family drama in which shocking revelations come one after the other but never reveal anything for certain. The characters are in constant conflict with each other, though it’s often difficult to determine why. Sudden outbursts, yelling and threats, then equally sudden reversals to proclamations of endless devotion. Murky symbolism that’s more confusing than disquieting, like eating a dead brother’s eyeballs out of desperate love. A hectic but paradoxically static book that goes on and on. High-pitched, kind-of-Shakespearian tragedy, but with a loose and painfully redundant narrative shape.

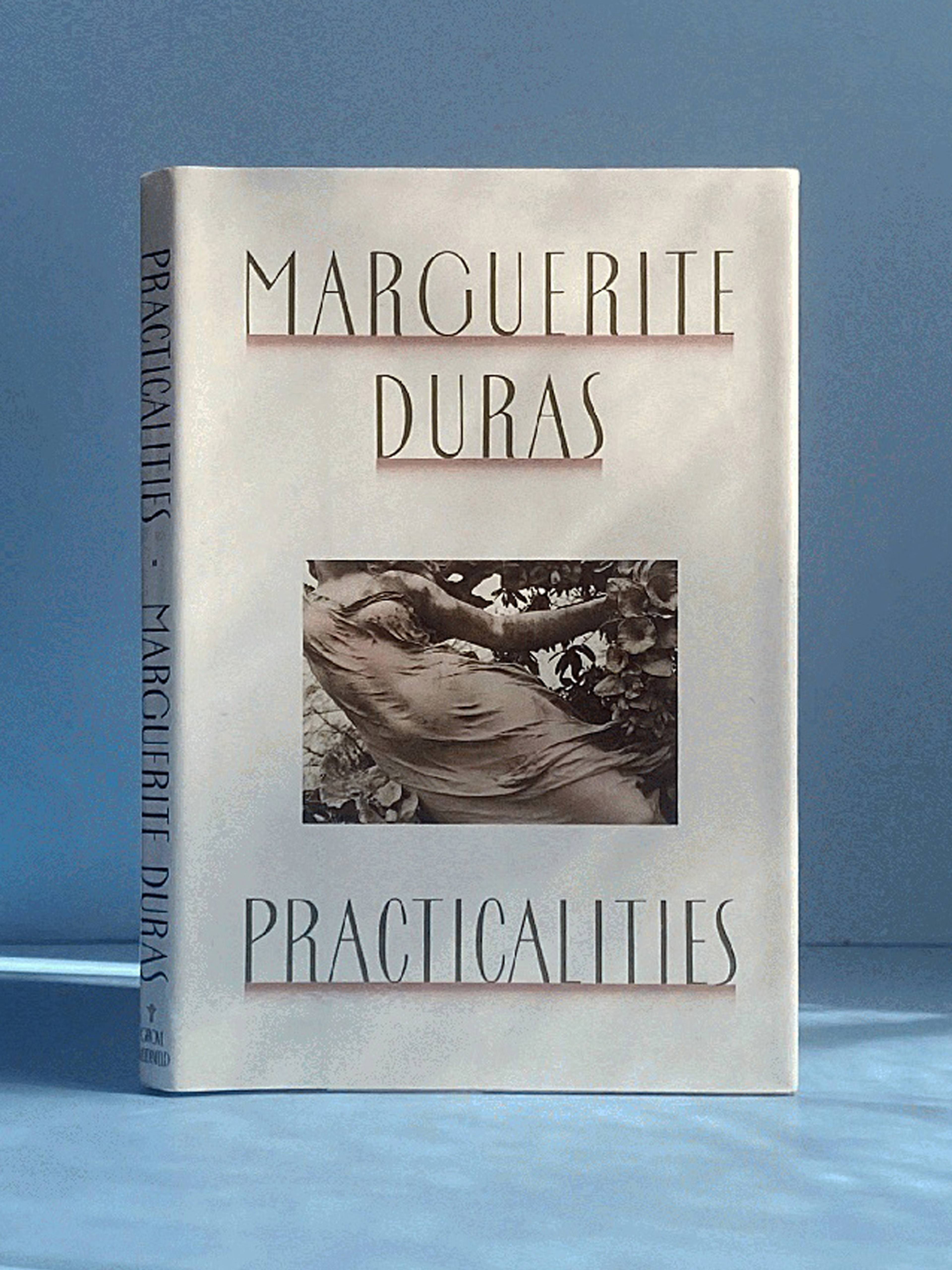

Marguerite Duras, Practicalities (Grove Press, 1992)

“A man who drinks is interplanetary. He moves through interstellar space. It’s from there he looks down. Alcohol doesn’t console, it doesn’t fill up anyone’s psychological gaps, all it replaces is the lack of God. It doesn’t comfort man. On the contrary, it encourages him in his folly, it transports him to the supreme regions where he is master of his own destiny … Alcohol’s job is to replace creation. And that’s what it does do for a lot of people who ought to have believed in God and don’t any more. But alcohol is barren. The words a man speaks in the night of drunkenness fade like the darknessitself at the coming of day … I was withdrawn from the world – inaccessible but not intoxicated.”

Fernanda Melchor, Paradais (Fitzcarraldo, 2022)

Relentless first-person narration that seems to offer a sociological and psychological context for an act of brutal violence, the murder of a wealthy family in a gated community in Veracruz, Mexico by two teenage boys, one rich and one poor. The book not only asks the reader to identify with and understand the narrator, but to enjoy a stream of confused, angry, and violent thoughts. It’s propulsive, appalling, and a blast. Written in a fast-paced block of prose so there’s no place to rest, no outside of social claustrophobia and no outside of solitude. An absolutely not condescending novel.

Rick Veitch, Rabid Eye: The Dream Art of Rick Veitch (King Hell Press, 1996)

Amazingly rendered in stark black-and-white, each page is a graphic strip of one of Rick’s alternately frightening, petty, and convincingly incoherent dreams. One starts with three men in a tub getting into a flub in a car leaking blood; then, in the next frame, a smiling man halfway transforms into light (captioned “Ezra”), followed by a close-up of hands cupping a giant novelty key (“a gift from Paul McCartney”), then a long, black train wreck (“Slow motion”), a wall (“west wall”), and a little frame of someone cheerfully saying, “Yeah so I think maybe we can actually inhabit past moments of our lives to experience new levels of meaning.”

Erje Ayden, Sadness at Leaving (semiotext(e), 1987)

A spy infiltrates New York literary circles – where it turns out that many of the other writers are also spies. The impression is that high culture is partially (or largely) manufactured by the conspiracies of intelligence agencies. Increasingly paranoid but deadpan, the book slowly works its way up to a hysterical ending where the main character repeatedly shoots himself in the knees. Ayden claimed he was a spy for the Turkish government, so it’s tempting to read the spycraft stuff as somewhat true to life, but any hint of realism is distorted by mangled genre conventions and really fantastic jagged prose.

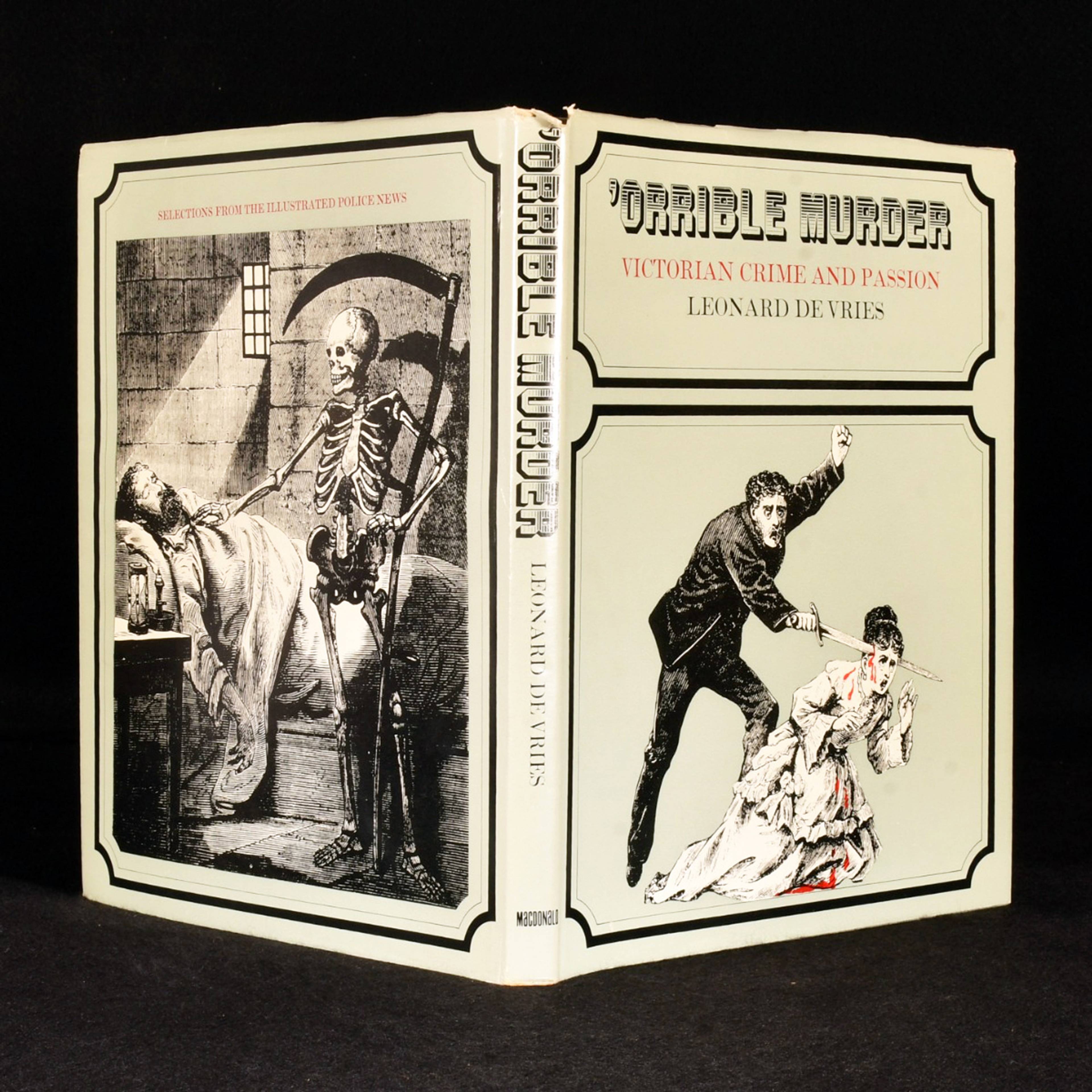

Leonard De Vries, ’Orrible Murder — Victorian Crime and Passion (MacDonald, 1971)

A facsimile collection of salacious articles reporting appalling crimes from the pages of a Victorian tabloid entitled The Illustrated Police News. Pre-photography – and per the paper’s title – each story is accompanied by astonishingly gruesome wood cut illustrations. “A SANCTIMONIOUS SCOUNDREL MURDERS HIS CHILD.” “A BALLET GIRL BURNT TO DEATH.” “AWFUL CRUELTY TO AN IDIOT BOY.” “FATAL ACCIDENT TO AN IMPALEMENT PERFORMANCE.” Etc. Very distant, somehow hard to parse, leaves you exhausted.

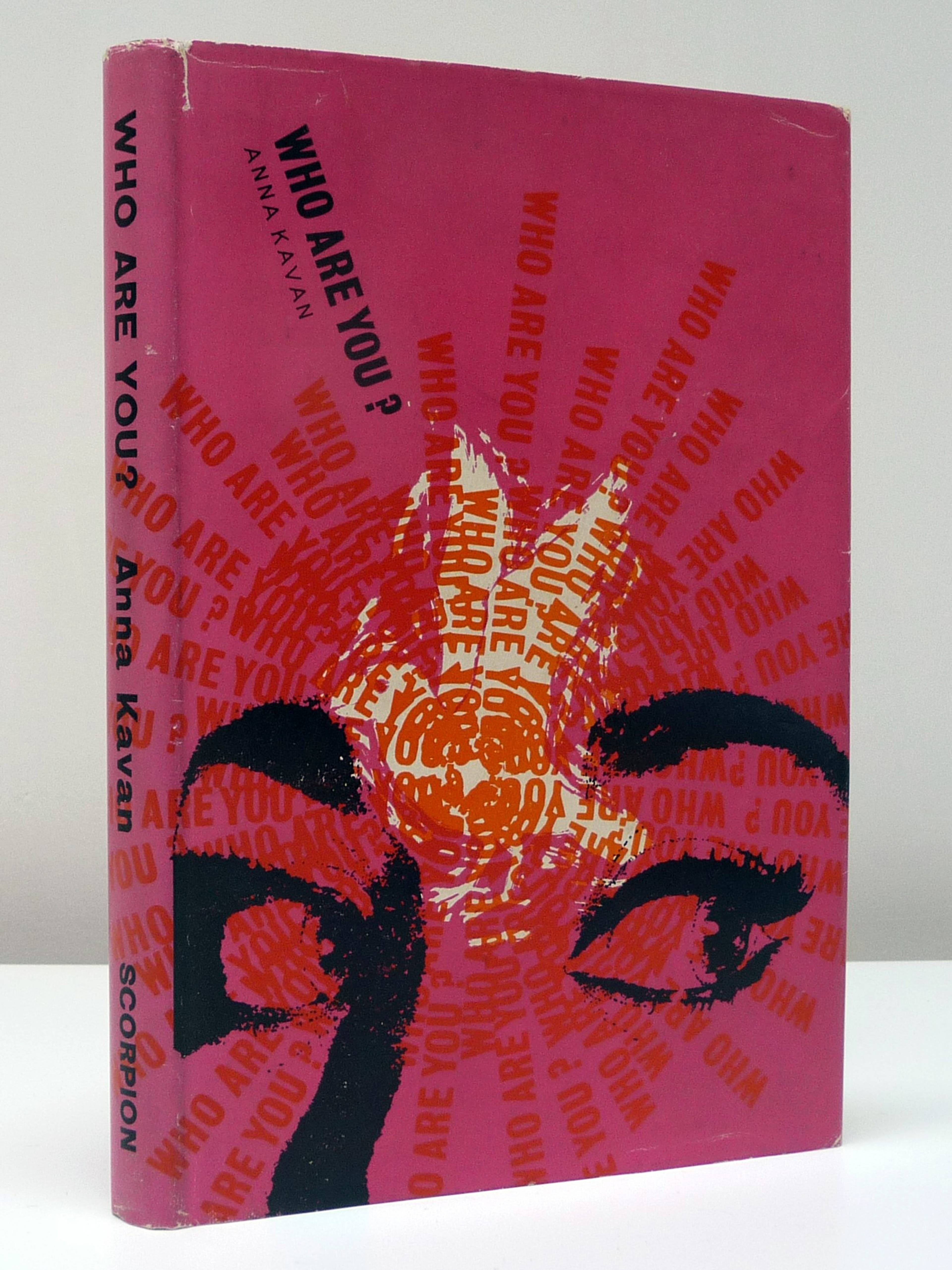

Anna Kavan, Who Are You? (Scorpion Press, 1963)

A semi-autobiographical account of a young woman trapped in a colonial outpost in Burma with an awful husband, referred to only as “Mr. Dog-Head.” The novel becomes more and more tense and desperate until it explodes in violence – but there’s no catharsis, because instead of a denouement, the plot then backtracks and repeats the climactic action with only small variations. It’s as if, no matter what, the characters are doomed to go through the same terrible outcomes in an imperfect loop.

___

For more fair-weather book recommendations, see Shane Anderson’s Summer Reads 2022.