Chaos Engines, Circuit Breakers

June is here (or it was) so I turn 30, pay some bills and see my sister IRL instead of just dm’ing her Shrek memes. During the same first week I have a conversation with an artist and project a question onto him I haven’t been able to shake since. Throughout this conversation each of us tries so hard to be sincere that nothing really passes between us but fictions and I noticed him making extreme eye contact and think of NLP "eye accessing" and other body cons favoured by head invader salesmen and PUAs. The question in question was "what are your politics" and he swam around it like a real politician before batting it back only for me to say, well, "I don’t like computers". This has become a running private joke, for me who spends most of her time jacked into one. Cables snake out of my pockets like spare limbs (or nerves) to a phone I rarely let die.

But I don’t like computers. Human computers, those schemers or worse distributors. Relentless paperclip maximiser types who buffet you with data packets until you relent and give them whatever they set out to get from you. I prefer machines with no purpose, who break or forget, who begin at the beginning and perhaps get lost among gardens of forking paths, rather than with ends in mind.

In his 2008 paper "The Basic AI Drives" Stephen M. Omohundro outlines the dangers of goal-directed systems, pointing to a number of “drives” bound to appear in sufficiently advanced AI systems of any design, “tendencies which will be present unless explicitly counteracted”. He suggests the systems will want to self-improve, will want to be rational, will want to preserve utility and prevent counterfeit utility, will want to acquire resources and use them efficiently. Oh no. I hate computer, but computer is me.

Photo: Ella Plevin

The analogy is crude, but defining the sort of behavior we find desirable isn’t a straightforward matter in either case, as Mark O’Connell demonstrates in a book I’m finding difficult to put down this month, To Be A Machine . His first chapter is prefaced by this elegant Don DeLillo quote, "Technology is lust removed from nature" , which tempts me to think again of the artist (and of all other artists) as a dissemination machine and feel, not for the first time, horrified. He will probably be pleased to find his character disseminated a little further here and in this case I’m a willing fool. But only in order to note that a strong will to disseminate could also be seen as self-governance by fear of death, as much a mortalitarianism as a totalitarianism, conquest and domination as “a destructive way out of all impasses!”

"I wonder what Musk’s six sons make of the Man in Black and his endless dark Nietzschean loops"

At some point during that same week I decide to destroy a few of my own impasses and impulses and end up on a dance floor with a dear friend surrounded by streetwear automatons shifting dispassionately from foot to foot while the friend and I skittle pin around a sticky, strobing dance floor like two of Ben F. Laposky’s oscillons. I consider suggesting a game: let us endeavor to tread on every inch of the floor that evening. Then decide against it and let the thought slip back out into the universe. Because I don’t want to be a computer.

Ben Laposky, Oscillon 520, 1960

Mad Dad Maximizers (All Cowboys are True)

Around father’s day I am forced to think about Elon Musk when he tweets that he is a socialist and prods my timeline into a welcome chorus of no-he-isn’ts. Musk is a disseminator. Of ideas and capital and labour violations but also of his own genes. Before he met Grimes, sorry c, he had an on-again-off-again with actress Tallulah Riley after telling her he wanted to show her his rocket. But before that he had six heroically named sons with a beautiful Canadian author named Justine Wilson.

Elon Musk is our dad too. Or at least presents himself as having a great deal of paternalism for the species. So it’s too easy to draw a connection between his desire for a multi-planetary humanity with this apparent desire for a multi-household family and suspect the will to absent-dad the lively inscrutable planet we call home as being basically shitty. He’s also said we’re probably living in a simulation, which, veracity aside sounds like a decent excuse to do terrible things. I for one will never call him Daddy.

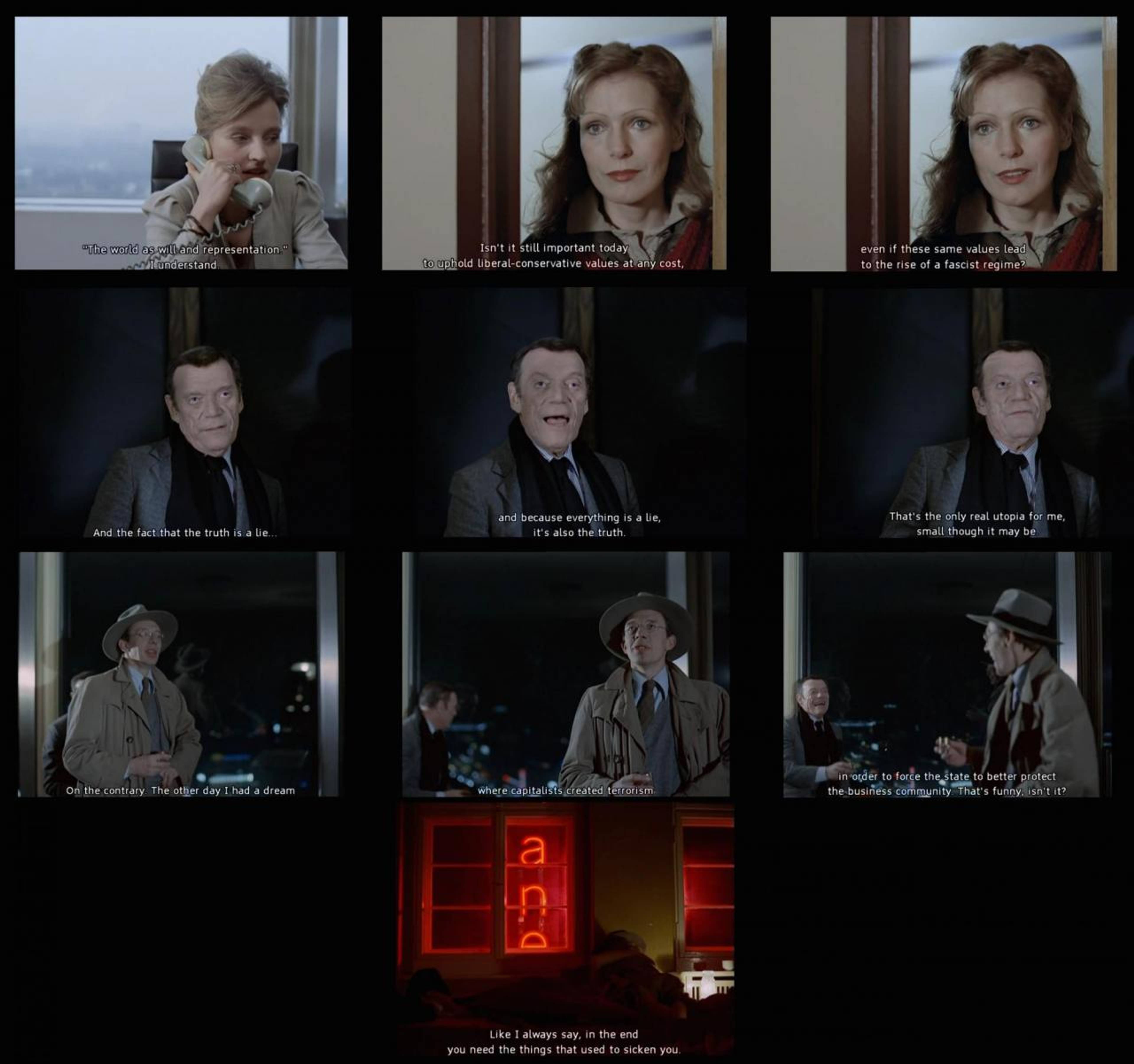

Stills from Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Die dritte Generation, 1979, 105 min.

This problem of (parental) responsibility inherent to all creation and action is part of the lifeblood of science fiction. It’s why the tale of Prometheus is so often used as a motif and I suppose this could explain why the final reveal of Westworld’s season two finale is named "the forge" rather than simply, Facebook. Another big Sci-Fi For Dummies (or technocratic capitalist evangelists comparing themselves to utopian anarchists) thing is questioning one’s shared reality, which Westworld does spectacularly. The final episode (which is also of course, an inaugural episode) roves between Inception, The Matrix, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, HG Wells’ "The Door In The Wall" and so many other incendiary tales smelted down to a titanic story about (most reductively) consciousness and mortality. I wonder what Elon’s five sons make of the Man in Black and his endless dark Nietzschean loops.

"There is no such thing as the end of the future"

At the end of the month I attend a launch for James Bridle’s new book New Dark Age: Technology and the End of the Future . The future has ended innumerable times already – indeed “nothing ages as fast as the future” as Stanislaw Lem put it somewhere in the 60s – but pessimism still sells at good prices. Brecht said that last part in his 1935 essay about Truth, considering that "such pessimism would be more fitting in one who observes these masters and their sales" and I admit it sat in me as I watched Bridle’s on-stage sell. At the end of the discussion an audience member asked Bridle a pointed question: "What is the personal significance to you personally in having written a book?"

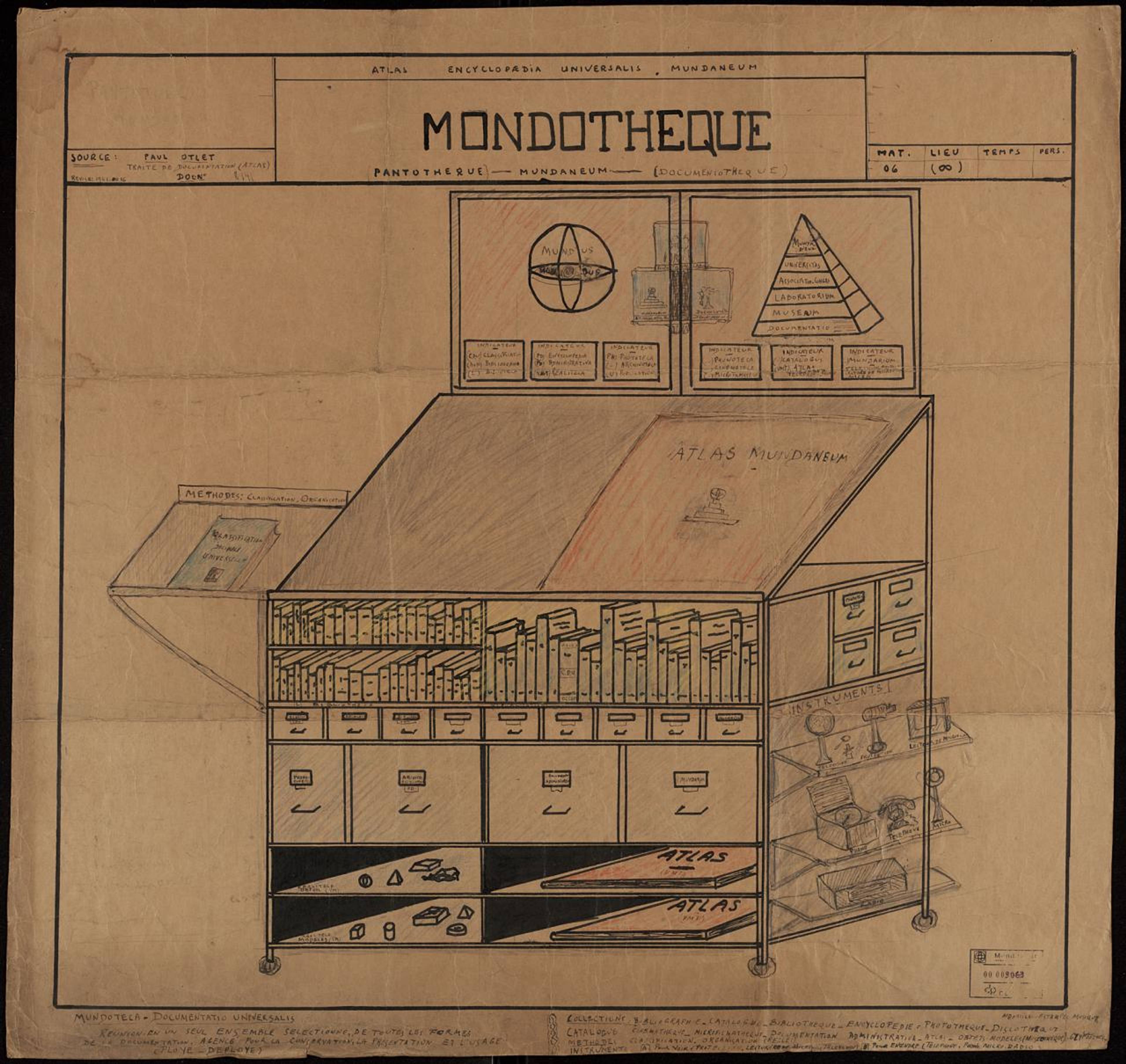

Paul Otlet, Mondothèque, 1936, ink drawing, 64 x 67 cm. The design envisioned a home multimedia workspace connected to a fully integrated global information network, a proto-internet of automated cross-references, one node in a larger world mind.

I’ve admired Bridle’s writing online but take a wrathful dislike to his millenarianism in person. I could brush off the vanity of painting his nails a rainbow ombre to match his new book jacket but not his enraging, absurd claims that “not many people look up at the sky” or that there is only now “starting” to be an interest in histories of computation, that these stories “haven’t been well told” or that he came up with the term “computational thinking.” I will read his book nonetheless but will be reading it with that audience member’s question in mind and will be thinking too of the Pulitzer Prize-winning, New York Times Best Sellers topping books of Sadie Plant, John Naughton, Tracy Kidder, Charles Petzold, James Gleick et al and of the myriad documentaries, blockbusters, prestige TV series and other stories similarly well told. Nevermind their more ancient lineage, of so many others who looked up at skies and down at their hands too.

If Bridle is to talk of a reckoning at the hands of a digital sublime he would be wise to look more closely into wetware data too, perhaps his own. Destructive gods and fathers (our bad dad maximizers), (con-) artist scammers and cult of will-to-power bro theorist philosopher kings alike all hit their marks by saying things are simple when they are complex or that they are so complex when they are so simple. There is no such thing as "the end of the future;" it is a claim made regularly by proselytizers and aspirant megalomaniacs. Thugs in high castles drawing lines across sands. I suspect this is my politics: either to dissolve their cloud-capped towers and tear their gorgeous palaces down, or simply wait for their pageantry to fade.

Peter Saville for Yohji Yamamoto Autumn/Winter 1991