Speaking as someone who does not have a trust fund but did study visual art in London, my post-graduation search for space was less for a studio of my own than a shared corridor of sorts within a former factory. When my name finally reached the top of a lengthy waiting list, I had to prove my professional status to be admitted; moreover, having cleared this hurdle, I was expected to be grateful for the opportunity to contribute to the costs of shared equipment and rent. In the end, I worked so many minimum-wage jobs to afford my place at a table I had no time to sit at that I gave up on trying to make art (and the myth of meritocracy along with it). Similarly, whenever I begin a book in which a wealthy woman stands, sighing, behind an easel, I think enough is enough and immediately give up on this, too.

At the same time, it’s easy to see why pretty fictions in which a “sensitive disposition” is all it takes to be an artist dominate our bookshelves, while the artist’s need for cold, hard cash rarely features. Novel writing (and reading) has historically been a conceit of the upper- and upper-middle classes, where such issues are, presumably, irrelevant and déclassé. Now, though, writers are increasingly emerging not only from the traditional university, but also from the modern art school – an institution partly begotten by industrialization and the birth of museum culture – just as publishers and agents are attempting to platform more authors who identify as marginalized, whether due to their race, sexuality, or (occasionally) class.

Sinéad Gleeson’s Hagstone, Rachel Cattle’s UH HUH HER, and Hannah Regel’s The Last Sane Woman (all 2024) are three recent debut novels that illustrate the effects of these changes within the literary landscape. Written by women with realistic knowledge of art-making, as well as of working-class life, all three describe the struggles of the contemporary woman artist in all their grueling, contradictory, but sometimes rewarding detail, and as something other than a stand-in for upper-middle-class hacks.

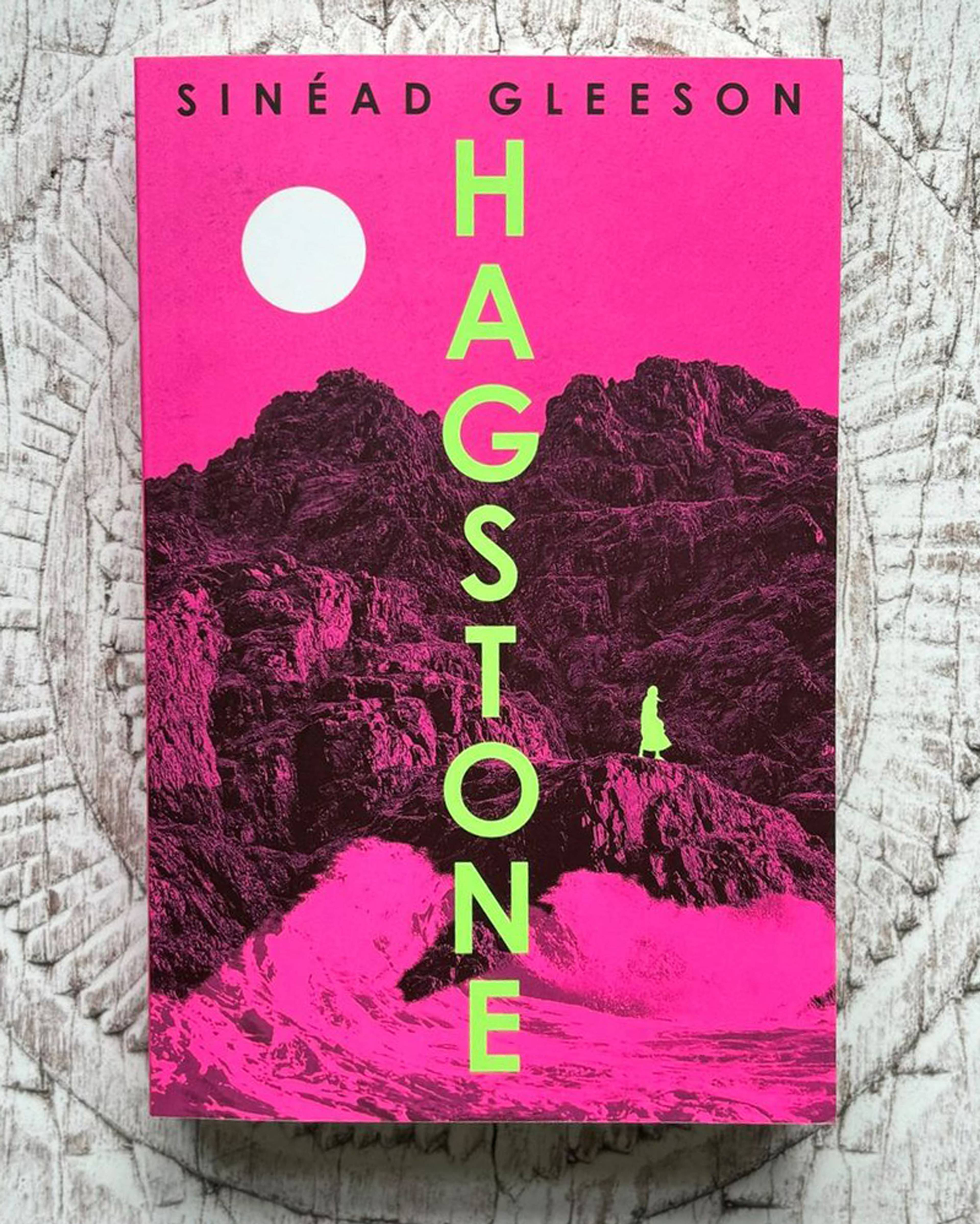

Sinéad Gleeson, Hagstone, 2024. Courtesy: 4th Estate

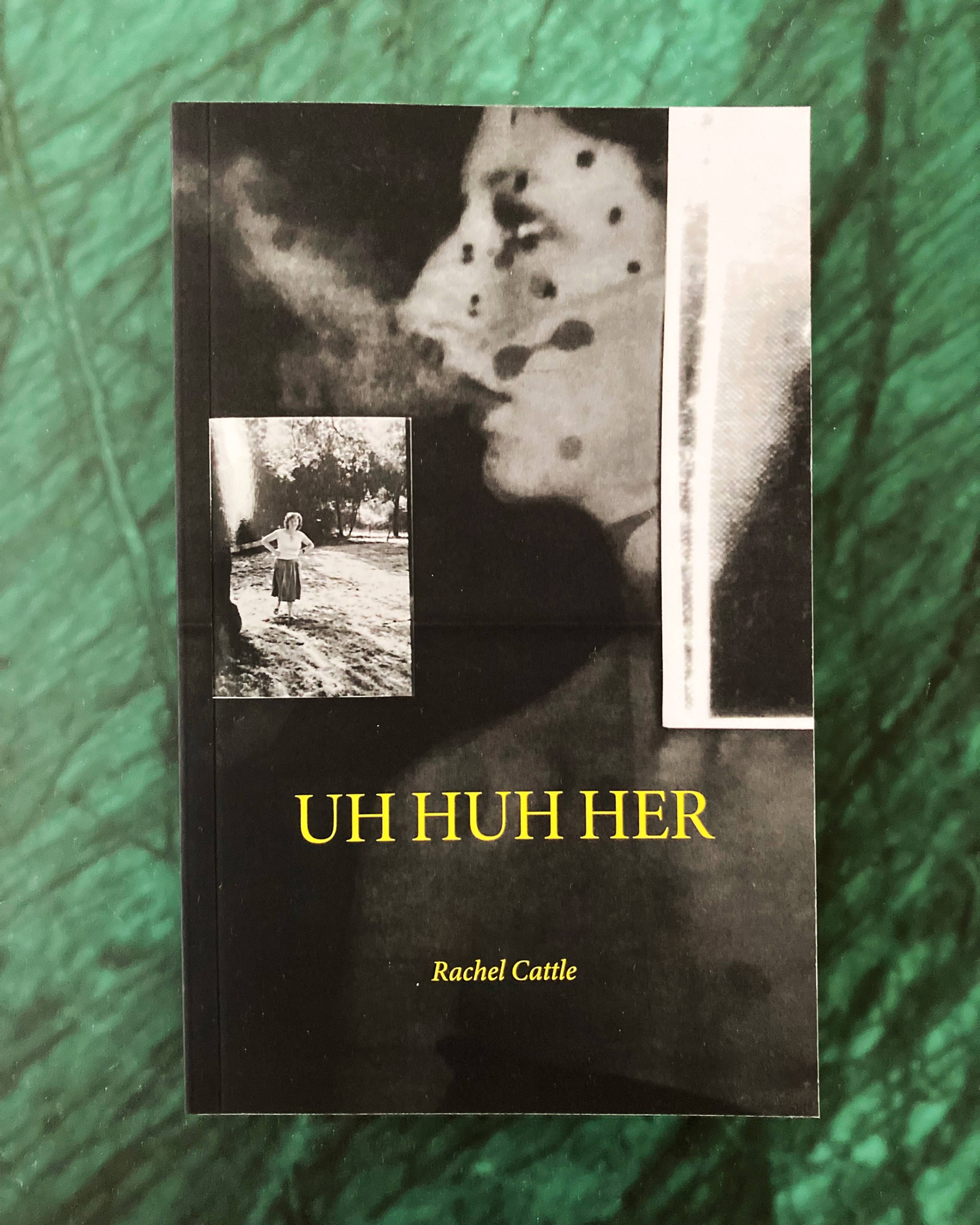

Rachel Cattle, UH HUH HER, 2024. Courtesy: MOIST

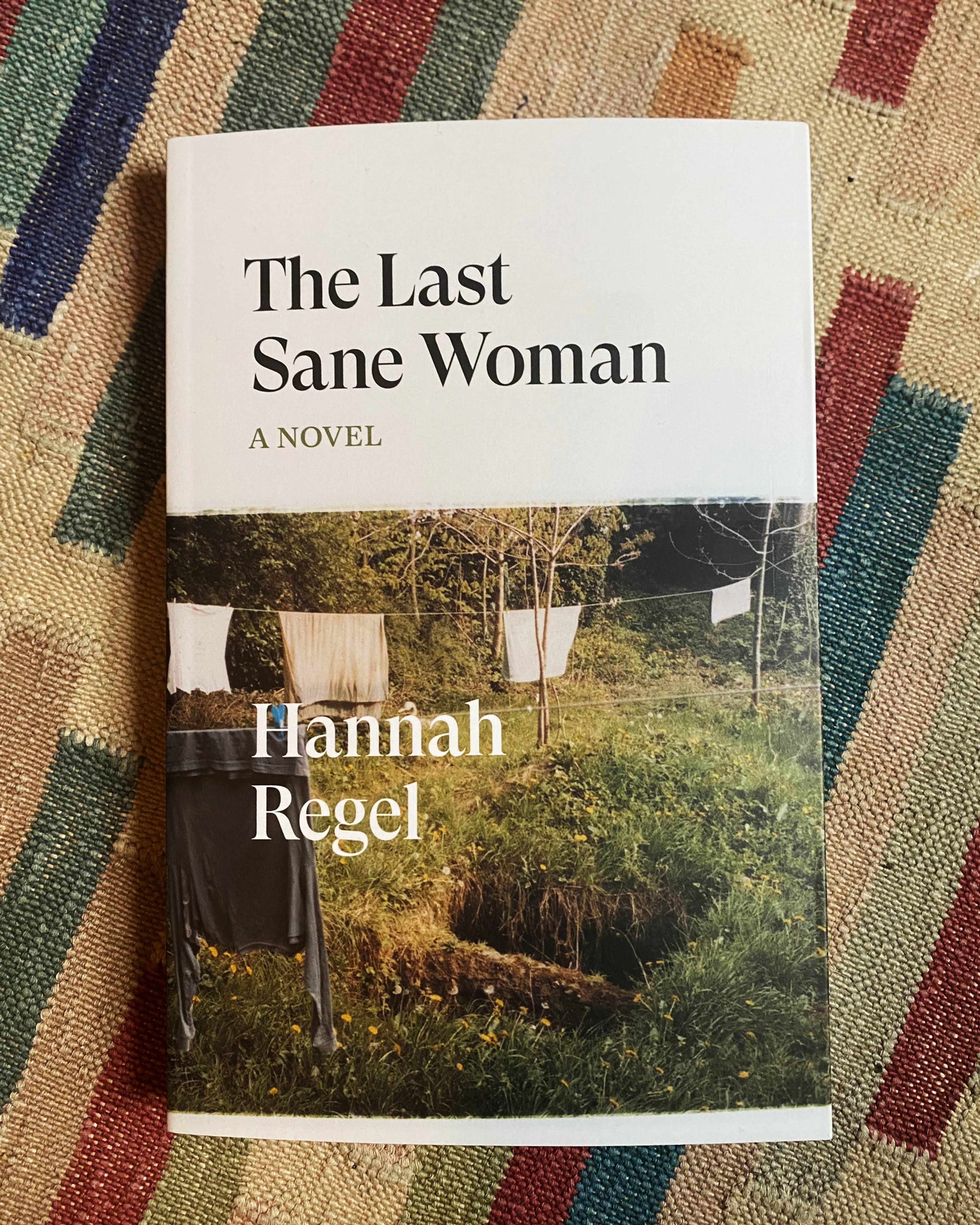

Hannah Regel, The Last Sane Woman, 2024. Courtesy: Verso Books

Hagstone offers little in the way of artist-protagonist Nell’s backstory, besides a few hints as to her previous life: international exhibitions and press coverage that ended before she turned thirty. After “receding from the world with its grief and inequalities” (or a rootless existence of bad hotels and unaffordable airport coffee), she establishes herself on a remote island, where she continues to produce complex, multimedia sound pieces funded via seasonal work as a tour guide. It’s a precarious existence: bad weather means no visitors to the island and no money. Yet, when the offer of a well-paid residency linked to greenwashing arises, she turns it down: “But if I wasn’t doing that, I’d still be an artist who cleans other people’s toilets.” An observer who believes in art for art’s sake, Nell sometimes bemoans her recent lack of recognition, but she also appreciates the freedom that comes with it.

In the same vein, Cattle’s UH HUH HER is the story of a woman who, despite – or because of? – her poor economic circumstances becomes defined by her belief in the importance of making art. Beginning “in the studio I barely afforded, impossible after the third rent hike,” Cattle’s unnamed narrator often resembles Lizzie, the artist-turned-art-college-administrator in Kelly Reichardt’s 2023 film Showing Up. Like Reichardt’s character, Cattle’s is similarly protected and restrained by the institution in which she studied at and works for – in this case, as a lecturer. She, too, is exhausted by attempts to navigate overlapping but often contradictory roles, and at one point illustrates her unease with a description of how a colleague “texts dark images of paintings she was making late into the night,” then titled the series “Management.” Later, she considers how “an afternoon of writing a grant application can fill you with so much dread you wonder if the teaching job you once had was actually a better option, the one that almost killed you.” Where Hagstone ends with Nell moving on, but nonetheless buoyed up with ideas for new work, UH HUH HER concludes as the narrator draws a tarot card indicating “a time of opulence and luxury [...] All of this is due to one’s intelligence and self-control and represents an achievement that has lasted over a lifetime.” To put it another way, both books share one message: that, ultimately, artists’ material toils will be spiritually rewarded.

Success within the current gallery system means that multiple pictures of the artist’s glamorous self, friends, and studio need to be in constant circulation.

Unfortunately, however, balancing the day job, or taxable hours doing tedious things, with one’s own creative endeavors is not the only issue facing “real” women artists. There is also the additional, emotional labor of making “work-adjacent images.” Success within the current gallery system (rather than the ability to “just” keep making work) means that multiple pictures of the artist’s glamorous self, friends, and studio need to be in constant circulation: a state of affairs and/or filters that tends to place greater pressure on women than on men. Yes, women writers still engage with style magazines, fashion campaigns, and post on their socials, as do women in every “entertainment” profession (as do men). But Ottessa Moshfegh for Miu Miu is an exception; Anthea Hamilton for Loewe is not – issues that The Last Sane Woman addresses.

In some ways, this book’s structure is akin to last year’s arts-administration murder mystery, Innominate, in which curator and critic Naomi Pearce contrasts the struggles of a would-be analog photographer in the 1970s with a digital re-toucher in the present day. Regel also employs a split timeline, juxtaposing the stories of Nicola and Donna, two ceramicists from these same periods. Nicola, the younger of the two women, has recently come across the archived letters of the older, now deceased one. When not pouring over these missives, she posts “photographs of the objects she’d made to the internet with the same fervor as she posted her face”; accepts an invite for a dinner hosted by Women in Clay, an event where the attendees’ “feminist” outputs feature in a Vogue Christmas gift guide; and understands that these woman, like every other artist of today, are into “staging”: “‘Take a picture of me in front of the Rego,’ [...] Four women immediately crowded round.” Reading Donna’s words, Nicola discovers that she shares her creative ambitions, financial concerns, and depressive episodes; and yet, there is now the additional worry about how each of these things is or is not presented through an online persona. In Pearce’s novel, this splitting between women’s virtual and physical existences in different eras highlights how images can be continually (re-)constructed to tell new stories. Meanwhile, Regel – who, unlike Gen Xers Gleeson and Cattle, grew up with the internet – underscores how the image of the self now undergoes the same process as the author’s actual art, rather than “just” investigating each sacrifice the artist makes.

Hagstone, UH HUH HER, and The Last Sane Woman depict sometimes wildly different artists’ realities through the authors’ sometimes wildly different literary styles. Tinged with Irish Gothic and folk horror, Gleeson’s Nell is independent, promiscuous, and unaffected by what other people think, her sound works simultaneously in tune with the island landscape and overwhelming the islanders. Cattle’s “I” is more reticent: Drawing in snatched nighttime moments and writing her reflections on scraps of paper she keeps in a carrier bag, her shifting, fragmentary life brims with motifs from the British avant-garde. Regel’s Nicola is perhaps the most conventional – or lost? – of the three characters, her attempt to create a template for her own life by re-ordering Donna’s letters fittingly dictating The Last Sane Woman’s “split,” semi-epistolary narrative.

Nevertheless, each author asks the same fundamental questions about the value and price of making art in relation to class politics – questions that are often absent in novels where the woman artist exists only to physically manifest certain aspects of the woman author, a “crime” of which even great novelists are guilty (A.S. Byatt, Siri Hustvedt, and Iris Murdoch, to name but three). My intention here is not to present one group of novelists as “better” than the other (or to say that the real-woman-artist is any less of a construct than the fake-writer-artist, or indeed than literary “realism”). It is a plea for awareness as to how irritating these latter types of books can be for anyone whose been really, truly, actually broke while struggling to keep their creative identity intact. There’s enough stories about poor women artists who speak in the voices of rich women writers out there to last a lifetime. Personally, I’d rather dirty my hands with “grief and inequalities.”

___

Sinéad Gleeson’s Hagstone, Rachel Cattle’s UH HUH HER, and Hannah Regel’s The Last Sane Woman are available for purchase from 4th Estate, MOIST, and Verso Books, respectively.