If our deepest selves are increasingly exhumed through data collection, processing, and automation, the massive impacts of blackbox algorithms on work, education, romance, nutrition, political leadership, and even notions of selfhood should occasion widespread alarm. In 2017, artist and researcher Mimi Ọnụọha wrote a GitHub post reflecting on algorithmic violence, a term she coined to describe how probabilistic code aggravates structural vulnerability. Turning away from Big Tech’s dominant technological imaginary, the Brooklyn-based artist entwines low-tech source materials in digital infrastructures to yield more expansive narratives for social existence and to surface the contradictory logics at the heart of corporate utopianism.

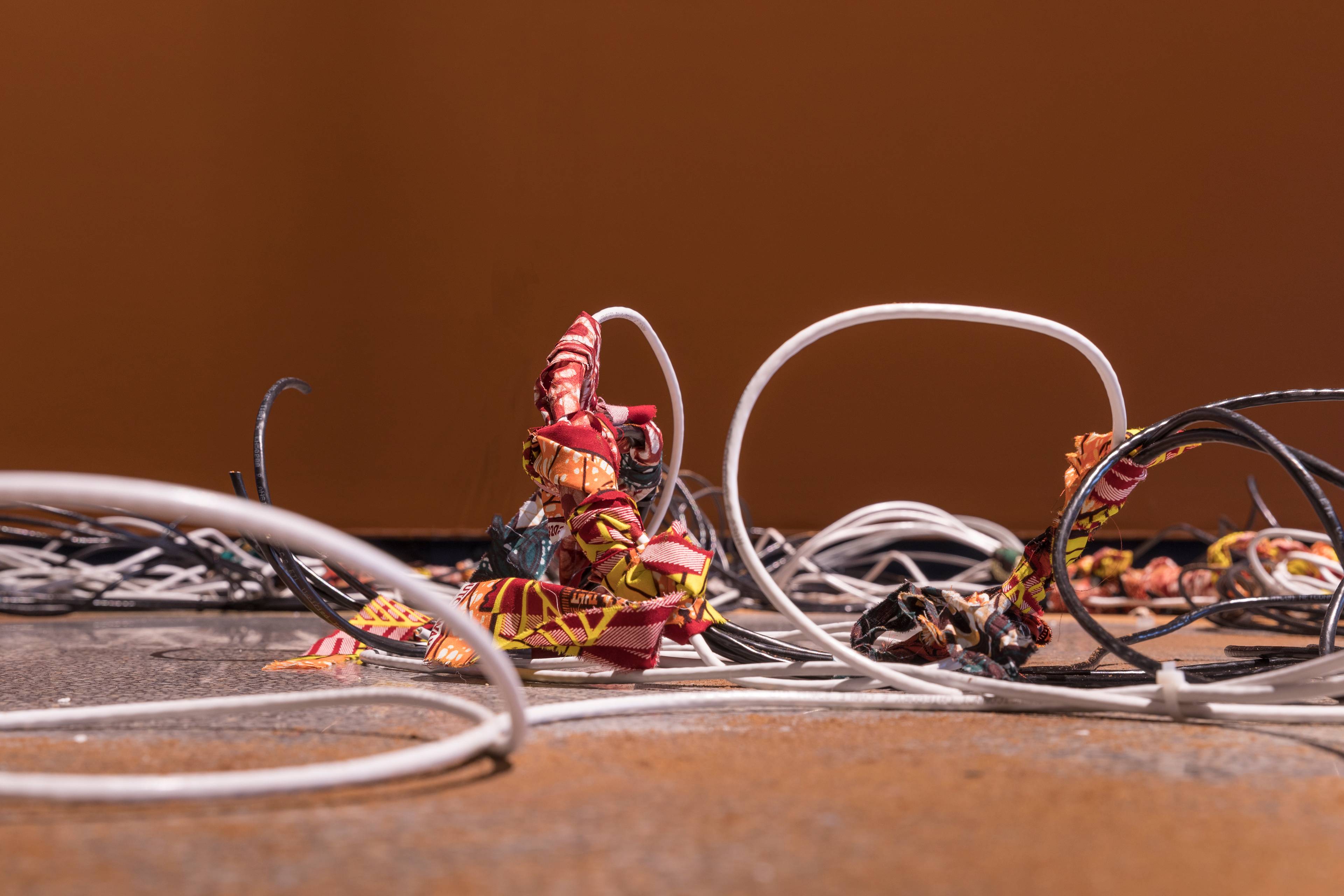

Alexandra Gilliams: In your installation The Cloth In The Cable (2022) and the accompanying film, These Networks In Our Skin (2021), internet cables are laced with strips of fabric and hair, then dusted with spice that infuses the exhibition space with scents. What metaphors do these adaptations refer to, and why interweave them with infrastructural technology?

Mimi Ọnụọha: I frame my practice with a quote from the physicist and theorist Ursula Franklin that describes how our lives are being pushed into a house that technology has built. We don’t always get a say over that process. That house is still being constructed and deconstructed, though, and these works suggest how we can contest certain visions of the data, information, and knowledge flowing through these channels. There are many ways of knowing the world.

Much of this work is directly pulled from Igbo cosmology, and there’s a theme of repair that runs throughout the video installation, which features four women opening cables, weaving them with new items, and closing them back up again. What’s woven in fluctuates depending on where the work is shown, but there are always spices, cloth that is usually locally sourced, and sometimes hair. There’s a color palette associated with tech that I call AI blue, which has its own connotations. I wanted something warm that pulls from the village that I come from and brings that feeling into the space.

I usually work with a collaborator who comes from the place where the installation is presented who brings in local elements. Art is so often a commodity that travels the world. What does it look like to move away from a standardized, universalized artwork, and to instead have one that encounters the world contextually?

The Cloth in The Cable, 2022 and These Networks In Our Skin, 2021. Installation view, Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, Melbourne. Photo: Andrew Curtis

The Cloth in the Cable, 2022. Installation view, Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, Melbourne. Photo: Andrew Curtis

Still from These Networks in Our Skin, 2021, moving image (looped), 5:48 min

AG: Let’s try and dismantle this “house.” Your recent video montage Machine Sees More Than It Says (2022) contains archival clips from the 1950s–80s of computer systems and the workers who make them function. You said that the computers seemed to be “intervening to speak of themselves.” Could you elaborate?

MO: I’m captivated by the myths and stories that fuel our understandings of technology, which archival footage makes easier to feel. When we look at a technological device, it’s simple to see it is as one cohesive object that enhances our capabilities in a mostly uncomplicated manner. Machine Sees More Than It Says extends that story like hands stretching dough. We see the network that devices are embedded within, from the minerals that are mined to produce them to the people who shape and form them. Each step becomes its own world, and, in doing so, pushes against the tendencies of erasure that characterize some of our industrialized, globalized societies.

AG: Your 2019 video The Future is Here! emulates the language of pipe dreams that tech companies constantly use to distract us from the accumulation of massive profits and the exploitation of invisible labor. How has art helped you to navigate this hyperbolic rhetoric?

MO: It’s interesting to me how much of the tech industry is based on myth, even though it purports to be coming from science. The storytelling is so important. Climate writer Dougald Hine said that science is synonymous with knowledge, but that the facts it provides fall short, so it presents knowledge that isn’t all there. There are questions about judgement and normativity that are upstream from science, which is where art intervenes.

AG: You coined the term “algorithmic violence” in 2017 to describe the violence that algorithms inflict by aggravating political, social, and economic divides. What is the context for this idea, and how has it developed as AI has crept deeper into our lives?

MO: I come from the fields of anthropology and art. I thought that we needed a phrase that highlights how these new digital tools, systems, and networks interlock and operate on top of forms of structural violence that have been around for a long time.

What is oddly compelling about these newer computational systems is that they make violence neater, more categorized. For example, there’s something very simple about a model discriminating against women by showing how it does or does not include them. It turns what is actually a difficult predicament into a problem to be solved.

Knowledge doesn’t simply come to you; it also involves what you yourself and the space you’re in will allow you to know.

AG: Absence, or the lapses that occur during data collection, is a thread that connects most of your works. You’ve mentioned systemic racism and emotions as examples of what can’t be quantified or labeled. What else would you add to that?

MO: One of the thorniest issues that really fits into this is grief. When thinking about war, we’re looking at one dimension: How do you count the people who have died? What does that do? Does that number hold a life? Our lives are truly anecdotal, even though we constantly turn to statistics to try to make sense of trends.

I’m looking not only at what is unquantifiable or missing, but at what is unknowable. Knowledge doesn’t simply come to you; it also involves what you yourself and the space you’re in will allow you to know. Things can be missing, but there’s also the unknowable lying outside of what constitutes your framing of the world.

AG: You’ve represented this idea very directly in your neon-tube sculpture Classification.01 (2017), which, shaped like computer-programming brackets and equipped with facial-recognition technology, lights up whenever a viewer’s face matches some parameters that remain undisclosed. How do you think the rapid deployment of machine-learning is affecting our agency?

MO: A strange phenomenon with digital systems is getting classified and not knowing what group you’re classified into. You don’t have agency or the ability to organize with people – to commiserate and say we’ve all been affected in the same way. Classification can be a powerful tool: The consequences of being classified into an invented – but still real – category like race, for example, are extremely real. What it means to be Black is huge, and I’m proud of that, even if this was a category created out of a particular set of political, economic, and labor conditions. It can be empowering to be classified, but that relies on knowing and being able to come together with those you’ve been classified with.

AG: At the moment, it seems that AI is being developed to rapidly boost “automation” (powered by ghost labor), sales, and, to borrow from social psychologist Shoshana Zuboff, behavioral control. What alternative uses for data collection and machine-learning have you proposed with the upcoming project Ground Truth?

MO: Ground Truth stems from my hometown, outside of Houston, Texas. In 2018, the school district was digging to construct a new school when they found the remains of ninety-five Black people involved in convict leasing, a forced labor system that began after the US Civil War. People – mostly Black folks – charged with petty crimes were tried and convicted without a lawyer and sentenced to prison. As there was very little carceral infrastructure at the time, their labor was sold to others who were responsible for housing and feeding them. What some historians have called slavery by another name became – as is often the case in the US – a state-sanctioned way of solving an economic problem with a captive labor group that enforced racism and control.

Prior to the excavation, people were dismissed when talking about the grave; once these remains were found, suddenly, they had to be listened to, raising questions about what counts as evidence and the language through which truth can be acknowledged. There are probably similar graves across the US that are unknown and I thought I could leverage the “precision” of machine-learning to predict where they are. It was always meant to be an impossible model, because it couldn’t show the graves’ exact locations, just the likelihood that they’re there. You can have all the facts, and still, something remains missing.

AG: How do you train the machine-learning model in this context?

MO: The independent variables allow predictions to happen, ranging from the demographics of an area and its historical population, to land, industry, and census data, documented racial violence … There are always patterns. Violence happens in patterns.

The hard part, which I didn’t think would be hard, involves the dependent variables, or what we are trying to predict. We know which counties had convict leasing and these graves, but how can you prove which ones didn’t? While there are people who are willing to talk about this now – because we are in a moment where it feels like past events that were once clamped down on can emerge – that’s not everyone.

AG: It becomes a suppression of history.

MO: Yes, exactly. The very failure of this project reveals the problem. I’ve called many counties to ask if they had convict leasing. The answers people give are becoming another catalog of absence. Sometimes people say no, possibly because they don’t want to talk about it; or, they might not know about it, but that doesn’t mean it didn’t happen. What the project has always asked is, how or why do we trust certain epistemologies? In some of these spaces, people simply can’t know, because that would push against who and what they believe themselves and their towns to be.

AG: Where do you see us heading, with our lives increasingly implicated in data?

MO: My fear is that we will gravitate towards what is easy to receive – more data collection, models, AI applications – rather than what is needed: a way of making sense of the questions that lie beyond what data can tell us. We need to understand that the way a computer or model sees the world is one way of seeing, and though that vision aids with certain issues, it cannot save us from them all.

___