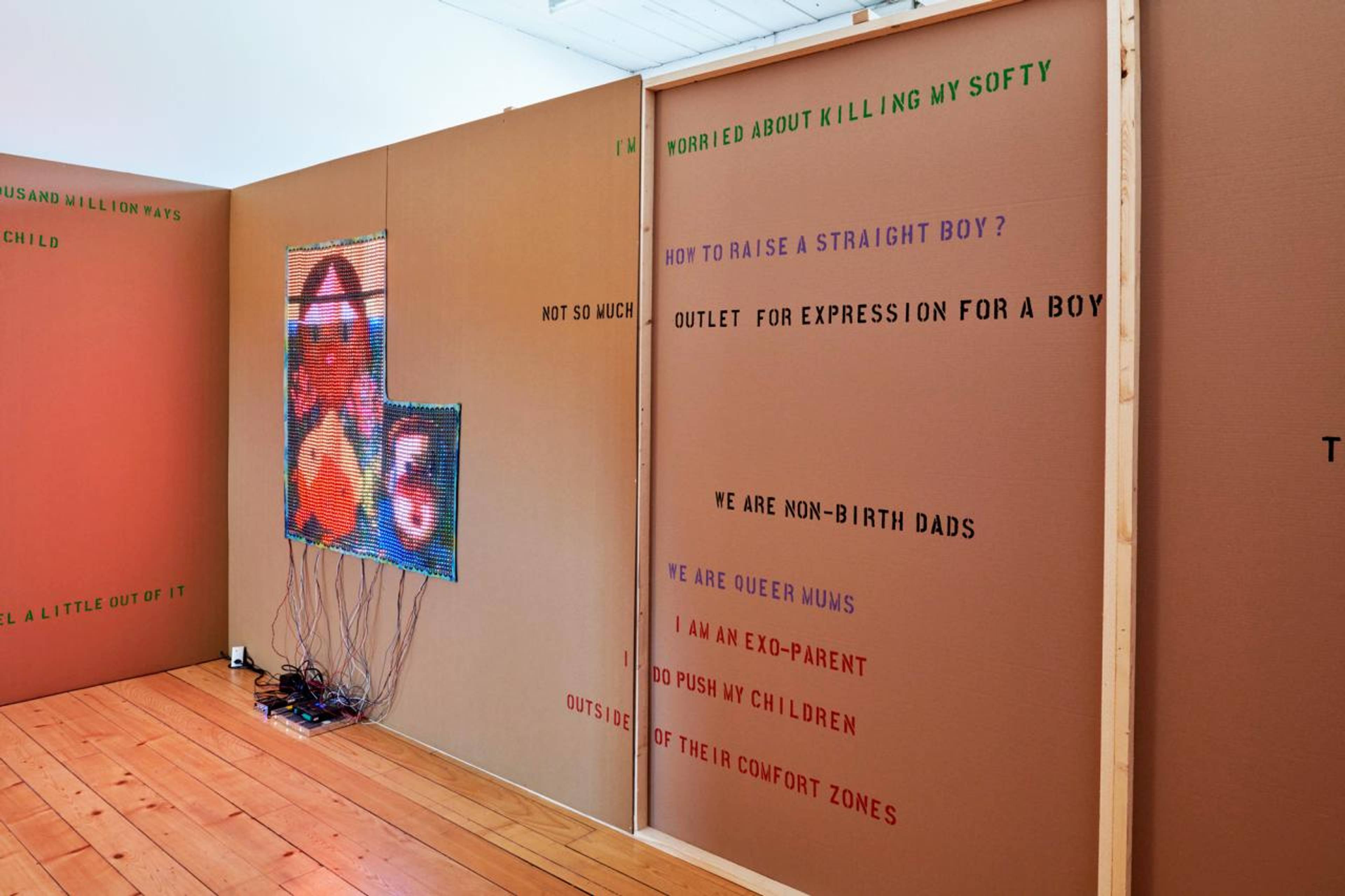

Ei spoke with three artist friends, all painters (Nicole Eisenman, Laura Owens, and Trevor Shimizu), to invite their perspectives on parenthood. He also imagined exchanges with two deceased artists (Alice Neal and Mary Cassat, the latter of whom never had children) in order to understand historical shifts in the model of the artist-parent. He then worked with the artist and composer Celia Hollander to turn these conversations into a libretto for synthetic voices, which sing out from behind LED reproductions of works by each of Ei’s subjects. These “figuring paintings,” as he calls them, are mounted inside a winding cardboard structure whose walls are stamped with the libretto’s lyrics, at the heart of which a circle of plastic babies in strollers debate the logic of their own births.

Leila Peacock: This installation is such a brilliant mixture of deranged elements – the bright LED “paintings,” the vocaloid opera, and the makeshift structure, not to mention the singing babies! Why was it important for you to address the subject of artists becoming parents, and why do it in this way?

Ei Arakawa: It’s a very real topic for artists of my generation. In New York, I had artist friends from an older generation who chose not to have children. The advancement of fertility treatment, though, has made it easier to have children in our 40s, around when artists become settled “mid-career.” There is a sense that the infrastructure is changing and that museums are (hopefully) changing their attitudes toward artist-parents.

View of “Don't Give Up,” Kunsthalle Friart Fribourg, 2023

LP: There’s a great talk with the late Phyllida Barlow where she remembers being asked at Goldsmiths in the late 80s if being an artist or a mother was more important to her. She describes the moment, “I thought I have to say it, so I said ‘being a mother,’ and almost all of the students walked out.” Do you recognize this sentiment in the artists you spoke to?

EI: Ha, yes! The three artists I interviewed for this exhibition all have multiple kids, and they have set up their studio practices much more methodically after becoming parents. I wanted to learn from their transformations. It has been especially hard for female artists to choose between being artists and being mothers. You know this kind of social conditioning, according to which artistry and motherhood are incompatible.

LP: Is that more about our prejudice toward mothers, or our romanticization of how artists work?

EI: Both, I think. Though I’m not going to be a mother, I wanted to communicate the way that the necessities of being a parent expose the impossible romanticization of artistic practice, the need for long hours in the studio, and this idea that creativity will drain away if one has children. I needed to research concrete examples of how artist-parents manage studio time, travelling for exhibitions, etc. The advice I received was very practical, and I used my exhibition to explore these practicalities. Potentially being a queer parent myself, there weren’t so many examples available, so I needed to build a network of people, to learn how they did it. How do my partner and I bond with our children without a mother present? And how do I develop a nurturing side without following a traditional “father” model? Though maybe in the 21st century, these are no longer only queer questions.

View of “Don't Give Up,” Kunsthalle Friart Fribourg, 2023

LP: In The Argonauts [2015], Maggie Nelson wonders if there is something “inherently queer about pregnancy itself,” but also how “an experience so profoundly strange” can “symbolize or enact the ultimate conformity.” Does that capture some of the anxieties and questioning captured in your lyrics?

EI: As one of the voices sings, there are “a thousand million ways to raise a child.” I commissioned an essay for the exhibition by Mark Pieterson, in which he discusses the “necessary yet contradictory social labors that renew and resist the diffuse workings of patriarchal and capitalist dynamics,” particularly insofar as these dynamics impact the unconventional work lives of artist-parents. Laura Owens also introduced me to the psychotherapist and art historian Rozsika Parker’s book Torn in Two: Maternal Ambivalence [1995], which furnished this sense of uncomfortable contradiction that was very helpful in creating this work, which is as much about coming to terms with the – perhaps conventional – desire for family as it is about embracing it. For the event that closes the exhibition, we will create T-shirts that say “I love my baby / I hate my baby.”

The interviewees also had a poetic openness and a collective generosity toward me as a potential new parent that comes across, which is also its own particular form of truth.

LP: I have this notion that humor is generated by a break in the symbolic order of things. How do you see humor function in your work?

EI: In general, in a performance, the audience always expects something from the artist, as a service provider or an entertainer. There is also a custom in theater in which an audience behaves in a certain way. I always want to break those expectations: I often tell them the performance has not started yet, so that their body and consciousness cannot track the beginning of the performance. Humor arises from their being thrown into a state of uncertainty. That is an integral part of my performance form, how I treat the audience.

In this exhibition, there are also a lot of models of parenting that are reconstructed into strange, liberating, and funny mantras. I had connected with the artists who I interviewed as a kind of parent-collective, and we all understood that parenting requires a sense of humor!

LP: I don’t think there are any exaggerations. Do you think a lot of it is funny because it’s true?

EI: That’s good to know. When I reduced the interviews into song lyrics, it produced something poetic, and that awkward jump can be very funny. The interviewees also had a poetic openness and a collective generosity toward me as a potential new parent that comes across, which is also its own particular form of truth. All of them have also made paintings of their children: Like Alice Neel before them, they are conscious of being in parenthood as artists.

Ei Arakawa, Don't Give Up (Mary Cassatt, Mother and Child, cir 1889, & The Family, cir 1886), 2022

LP: The work is described as a maze, but it reminded me more of a winding path. How would you describe the structure?

EI: When you go for the first time, it has lots of blind corners, and you can’t see where you are going. But the lyrics of the song begin at the entrance, and as you listen, it draws you through in a quite linear way, which helps the viewer to experience and consider the topic.

How was the music created?

EI: I often work with different composers. I met Celia Hollander at a concert in a Japanese garden in Pasadena, and I really loved how her music has a sort of uncanny instability, the opposite of a zen garden’s tranquility, as well as its own pacing. We worked with four vocaloids to create a voice for each painting, one for each interviewee. In the exhibition, those four voices and four baby noises create a chorus. It’s an eight-channel piece, with four speakers installed behind the LED paintings, each in a different part of the maze, so the space speaks in a kind of call-and-response. I respect the immediate way that music and sound can register emotion and set a mood. Even though sound is immaterial and sometimes precarious, it opens up the fixed, mazey structures of institutional architecture, and it circulates blood to my installations when I am not present for a performance.

View of “Don't Give Up,” Kunsthalle Friart Fribourg, 2023

LP: What can visitors expect from your live performance during the finissage?

EI: The performance on 13 May will take place in Les Bains de la Motta, which is a municipal pool opposite the Kunsthalle. I want to do a live version of “Don’t Give Up” with the participation of artist-parents from the community. I have never done a performance in a pool, but this is a big dream of mine that will finally come true!

LP: And are you now a parent?

EI: Not yet, because there are delays for surrogacy in post-Covid time, but hopefully next year. When we actually become parents, I want to make a YouTube channel to archive how we are doing. I’m from Japan, where there are still very few public voices of queer parents and the subject is very unspoken, as it’s the only G7 country where same-sex marriage is illegal. How shameful. So the afterlife of this exhibition is parenting in action.

View of “Don't Give Up,” Kunsthalle Friart Fribourg, 2023

Portrait of Ei Arakawa, 2021. Courtesy: Ei Arakawa

___

“Don’t Give Up”

Kunsthalle Friart Fribourg

11 Mar – 14 May 2023