Miranda July (*1974) is relentless. Talking to her, you get the impression that her every film, book, and performance is either a continuation, inspiration, or a prelude to her next project. The success of her directorial debut, Me and You and Everyone We Know (2005), made this evident to a wider and more international audience. Initially and falsely perceived as a specimen of urban sophistication – in an era that defined our ongoing idea of “hipster” – her work was never about witty, connoisseur references. Instead, it focused on the narrative possibilities of the mundane, the generic, and the arbitrary. An existential “what if” with hilarious and introspective dramatic outcomes.

Francesco Tenaglia: When your work began to circulate internationally, it was often framed by your involvement with the feminist punk movement Riot Grrrl. Looking at your early, sharp performances, the relationship is more evident today, more situated in a DIY, engaged aesthetics. How was it going back through this material?

Miranda July: I actually kind of missed Riot Grrrl by a couple years, but I certainly benefited from the ethos. At the time, living in Portland, I was very aware that, while I was a performer, I wasn’t “a girl in a band,” which instantly made me sort of Other, alien, even if all my friends were in bands and I lived in those spaces and record labels like Kill Rock Stars put out my work. You need some kind of frame at that age, and that very feminist and queer punk scene was mine. I dropped out of college pretty early on. I didn’t want to be taught, but to learn by doing it, and that small punk environment was perfect. In retrospect, I was so lucky – I had no idea how lucky I was. Also, to be surrounded by women, at a time when it was hard just to conceive of myself as a filmmaker, as a storyteller.

While I was organizing the documents for this show – it was a lot of work just psychologically to go through all the boxes – I understood how young I was at twenty-four. I kind of understood my career a little better, too. I was so focused on being a filmmaker that I didn’t want to acknowledge that I was doing performance. I’m a mom now, so I think that helped me see my young self a little bit from afar. I could see how oddly driven and rigorous I was, given the lack of training and so forth.

Views of “New Society,” Osservatorio Fondazione Prada, Milan, 2024. Photos: Valentina Sommariva

FT: Were you coming from an art angle, or was it related more to theatre or stand-up?

MJ: With girls, either you did ballet, or you did acting. Both are essentially daycare. I did ballet, but I dropped out and said, no, I’m going to the acting classes. I was a performer. I started going to the punk clubs and witnessing the Riot Grrrl scene, but the thing that spurred me, besides just being a fan of other people’s work, was actually a correspondence I had with a man in prison. In the exhibition, there’s just one reference to it, a flyer from a play called The Lifers (1992), based that correspondence with this thirty-eight-year-old man, a murderer. I wrote the play and directed it; I wasn’t in it because I was too self-conscious at that time, as a teenager. I cast real actors in it, and I put it on at an all-ages punk club in Berkeley. In a way, it kind of set the course for me – once I’d done everything myself, I knew I could do that forever.

I don’t want discomfort for its own sake, but sometimes, I use it to help the audience understand that they’re really here. It’s so hard to be aware of the present moment, but this is really happening, and anything could happen.

FT: The titular work of the exhibition is New Society (2015), wherein you and the audience stage the birth and first decades of life of a new community, circumscribed by the confines of the theater. New rules, new currency, a national anthem, loves, frictions, second thoughts – it’s a complex and fascinating work, a mini-utopia.

MJ: I’m the kind of person who’s always a little bit in emergency mode. Often, I’m thinking, what if something happened right now in this movie theater or wherever I am? How would this random group of people all deal with it? In my head, I’m in charge, and I organize everyone in this sort of fantasy. Meanwhile, I’d done all these performances with audience participation previously, and it had always bugged me that there was no real narrative reason why the audience was involved. So, it was thrilling when I had the idea of my audience and I forming a new society together. Finally, a sturdy conceit for all this participation! I was writing a novel with a deadline at the time, but I loved the idea so much that, every Friday for several years, I would let myself work on New Society. It was like my treat, my reward. And it had room for subtler themes, like my being a mom away from my child in order to work and the new complexities of that. And just relationships, marriage, just the whole artifice of having “a show,” and of course the fact that I can see them as they’re watching me. I get to watch the show that the audience puts on for me.

Audience participants in New Society, 2015. Brooklyn Academy of Music, New York. Photos: Julieta Cervantes

FT: In this work, mostly because there are a lot of parts played by the audience, but also in other shows, your character is hilariously awkward. There is the impression of instability, like everything could go in one direction or any other.

MJ: If you think of standup or a comedy special, you really want to know that you’re in good hands as an audience. It’s going to be funny enough, you’re going to be taken care of. Ultimately, this is true of my shows, too: I don’t want discomfort for its own sake, but sometimes, I use it to help the audience understand that they’re really here. It’s so hard to be aware of the present moment, but this is really happening, and anything could happen. Once I started making movies, I realized that quality is unique to live performance. A film audience really does just sit there: Nothing is ever going to be asked of you, and it is such a joy, such a pleasure, to just space out and give yourself over. That can be enjoyable in live performance, too, but I just felt like, since I get to make movies, why would I do that exact same thing onstage?

Through live audiences, I’ve become very sensitive to the shifting levels of attention – you’re living and dying up there. You can absolutely feel when they’re still looking at you, but their minds have left, and you just want to die.

FT: The exhibition also presents an iteration of your project with the artist Harrell Fletcher, Learning to Love You More (2002–09). You provided “assignments” to artists via a website, the fulfillment of which would take the form of an art presentation. In this case, a Milanese woman had to “make an exhibition of the art in your parent's house.”

MJ: I didn’t go to art school, and I was well into my twenties when I realized that, oh my gosh, I love art, and that the performances I was doing were art, even if I wasn’t crazy about the ramifications of art in the gallery world. Not long after this, I went home for Christmas. I looked around and thought, oh, these things that my parents have chosen to put on the walls – this, too, is art. It turns out I had never really looked at it, like I couldn’t even see it. All those pieces, these things, some of them literally just framed postcards – they all helped to make me. With this assignment, there’s an inclusivity to simply asking: What is art? What does all the stuff we add to it, to make it valuable, mean? I was so excited to do it here. I mean, just you put “Prada” on anything and it looks expensive, and for a lot of people who come in, they just want more product, just like the Met in New York carries a certain branding. I love getting to apply that to another kind of value. Also, I really wanted a piece tied to the place, to Milan, that would help me learn more about where I actually was.

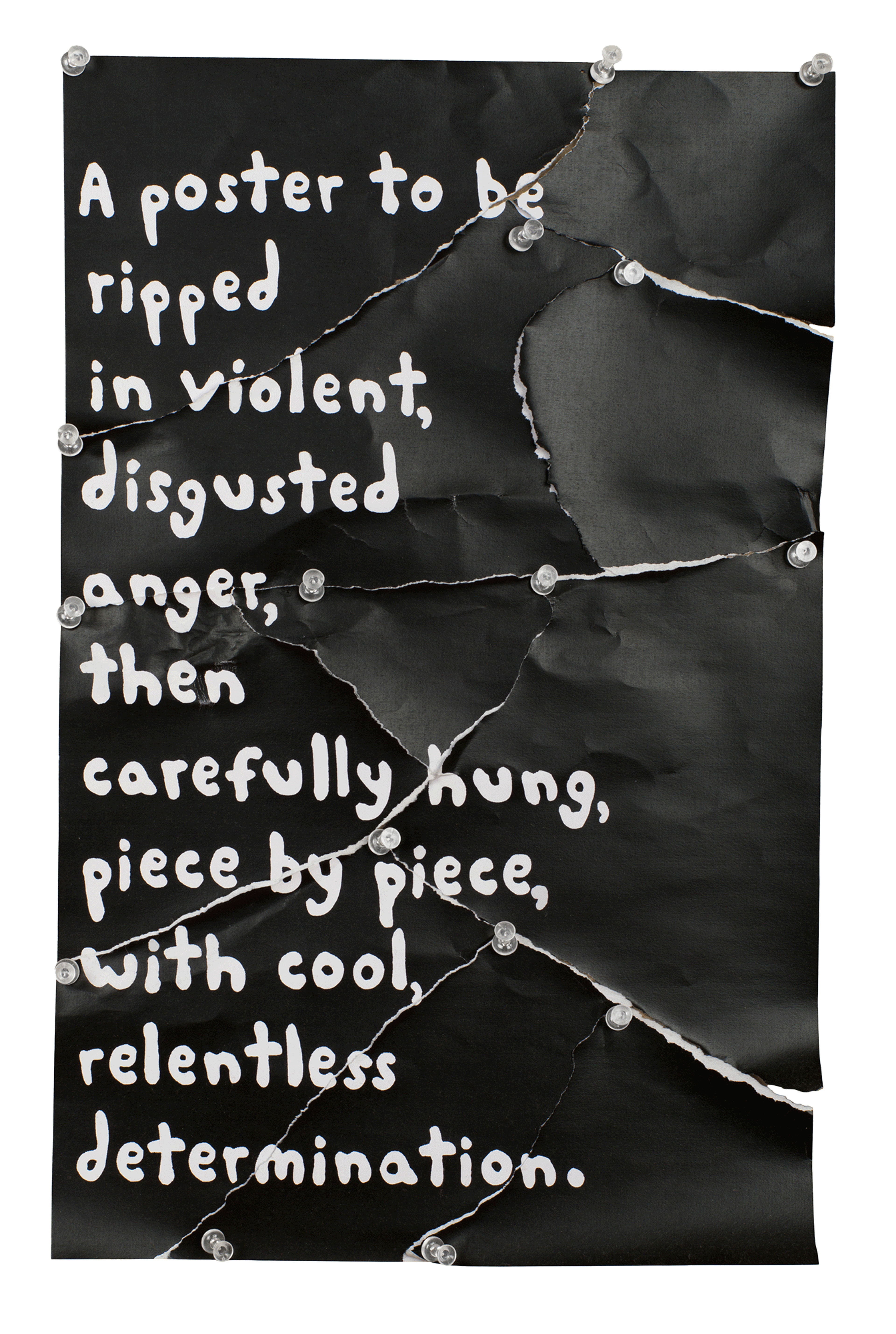

Ripped Poster, 2017

View of “New Society,” Osservatorio Fondazione Prada, Milan, 2024. Photo: Valentina Sommariva

FT: I believe that the project fits in an exhibition space like Osservatorio Fondazione Prada, also because it connects to other historical moments when the “value” of artwork was questioned: the found object, the exhibition as an artwork, and so on. What do you find interesting about visual art as a field?

MJ: It’s an infrastructure in which I can take risks that I absolutely am not interested in taking in my regular life. Most of the time, I just want to be left alone to think my thoughts, to write, to edit, but, in between every movie and every book, I work on these completely different ephemeral projects for which there is no market. You know what I mean? A book is a book, a film is a film. I enjoy being part of these old traditions, but in art-making, especially because I am not part of the art industry, I want to feel free to decide the shape of my new project, to invent forms. Because that option really only exists in the art world – that you can do this and not be considered experimental. Although, it’s funny, when I saw all my art and performance work together for the first time, it occurred to me that this was why I don’t have more money.

When I’m writing a book or a movie, the thing I want most is for the finished work to feel really alive. Through live audiences, I’ve become very sensitive to the shifting levels of attention – you’re living and dying up there. You can absolutely feel when they’re still looking at you, but their minds have left, and you just want to die. So, I think this is the greatest setup, working in all these mediums. I win all around, at least creatively.

Art is just … whoever walks in, for however long they want. Its economy really makes no sense at all – books and movies are like selling candles or cartons of milk or something. But there’s a freedom you cannot find easily elsewhere.

FT: Do you work differently, or with a different sense of scale, when you work for an art situation?

MJ: You would think I would learn how small the art audience is, and that the smallness would be a problem. But I get so excited about my ideas that, even if it’s just one room of people, it ends up being enough. It’s sometimes a little shocking to enter this world when you’re used to other industries’ massive infrastructures, the marketing and all those things. Art is just … whoever walks in, for however long they want. Its economy really makes no sense at all – books and movies are like selling candles or cartons of milk or something. But there’s a freedom you cannot find easily elsewhere, and the culture is changing: There are so many young people who think of themselves as artists but don’t care about the art world and in fact see it as part of a problem that art can solve.

View of “New Society,” Osservatorio Fondazione Prada, Milan, 2024. Photo: Valentina Sommariva

Stills from F.A.M.I.L.Y. (Falling Apart Meanwhile I Love You), 2024

FT: The newest work on show is F.A.M.I.L.Y. (Falling Apart Meanwhile I Love You) (2024–), a multi-channel installation in which you edited together videos of yourself and other people with whom you have communicated via Instagram, as if you were performing a two-person choreography in the same physical space. Would you like to tell me something more about it?

MJ: The seed of it came out of Covid, when I often took breaks from writing All Fours (2024) by dancing in my studio, and occasionally, I would post these dances on Instagram. I sort of felt like Instagram promised us that we would be looked at so lovingly, that we would finally feel okay, but of course, if they delivered on that, they would go out of business. There is never fulfillment, just more and more desperation to be looked at – which was kind of my experience of family as a child. And I thought, well, what would it even look like to fulfill that promise of intimacy? To have that level of connection with strangers on Instagram?

I formed a research group with seven strangers on the app. They sent me clips, and I wanted to bring these strangers into my studio and kind of move with them, to combine us somehow, sexually or maybe in a new way. I knew how I would do this in a feature-film context, but how would I do it alone, really quickly, again and again? Because I needed to shoot myself dozens of times to get it right, for our bodies to really connect. My child showed me these TikTok editing tools, and the results were really clunky – a head gets cut off, a leg goes missing. I loved that the technology was another way that the work was out of my control, and sometimes, it was so beautiful. It had all the things I loved too: using my own body, performing, a kind of fantasy. And directing: There was lots of back and forth with participants, forming this new, physical language together. I also brought in my sound designer, Kent Sparling, who I always love working with on features. He would be like, well, what actually is the sound of being swallowed? Of floating? And we’d be listening to recordings of deep sea creatures, trying to understand a world with less gravity. We ended up being very literal about it, to work against the surrealism.

The real challenge was to make a process that felt really good for the participants and myself. Despite the humor in my work, the looseness, the attempts to give up control or play with form, there is a kind of relentless, adrenalized backbone to my process that I’m less in the thrall of now. I know how to push everyone and myself to the absolute limit, but what would a process built around pleasure look like? It turns out it’s pretty hard! F.A.M.I.L.Y. was fairly rigorous in the end, but perhaps it was like a flag planted: Here is where I plan to feel good. In my family, in my studio, in my body.

___

A version of this text was published in Spike #80 – The State of the Arts under the title “Giving Oneself Over.” You can buy your copy in our online shop.

“New Society”

Osservatorio Fondazione Prada, Milan

7 Mar – 28 Oct 2024