Shimabuku: Where are you now?

Francesco Tenaglia: I’m in Berlin.

S: I lived there for twelve years!

FT: Oh, and where are you?

S: I’m currently in Okinawa, where I live now. It’s an island in the very south of Japan: You can say it’s something like Sardinia for Italy. It has a very unique culture. My father is from here and I wanted to move here for a very long time.

FT: Can you tell me about your recent exhibition at Museion, “Me, We”?

S: I was glad to be invited to do a show there, because Bolzano is such a special place. I’m thinking specifically of the fact that the population in the region, South Tyrol, has both Austrian and Italian cultural and linguistic backgrounds. I’m interested in exploring encounters of different cultures in my work. The piece I chose as the main image for the communication is, somehow, very telling: Kaki and Tomato (2008). It was a big show, actually the biggest I’ve ever had, though it wasn’t an organized, chronological survey of my work. The first floor had pieces from the 1990s onward, whereas the top floor was dedicated to couplings, such as an installation I made with materials taken from the medieval landmark Mauracherhof and a former Montecatini factory; buildings with very different characters, of course, both in the process of being restored or demolished. By working with discarded materials, I wanted to give them new lives as artworks and keep them together.

FT: This really resonates with the exhibition title.

S: Do you know where it’s from?

FT: Yes, it’s by Muhammad Ali, who said it when a student asked him to recite a poem during his 1975 Harvard commencement speech. He said only these two words, which have since been called the world’s shortest poem.

S: I think it’s beautiful and full of implication.

I want my audience to feel free, to feel that there are many different paths. To be more specific, I want them to feel as if every cell in their body is opening up.

FT: Are you interested in boxing?

S: In boxing as in many things, such as the Tyrolian alpinist Reinhold Messner. People believed that climbing Mount Everest required an oxygen mask, but he did it without. To me, that’s great art: He imagined, he believed, and in the end, he did it. I’m such a big fan of Messner’s, and I found the chance to pay him a visit twenty years ago. I’ve even had dreams set in the Dolomites. So, I have a history with the region.

FT: It’s funny you say that. I once delivered a lecture about fictional Alpine places in Japanese pop, inspired by Hiroki Azuma’s understanding of fan-fiction consumers as “database animals.” This idea of countries as completely synthetic was very much present in your exhibition, which emphasized an idea of “togetherness” against the frictions aroused by fixed cultural identities. And your work generally is strongly related to language, even if very obliquely.

S: Actually, I wanted to be a poet, but I thought I also needed translation, because Japanese is only known in one country. But the transition was very easy: When I was a teenager, I saw some work from Surrealism and Fluxus, and I immediately thought art could be a good “vehicle” for me. I still work with text a lot: In Bolzano, it wasn’t meant to explain the work, but was part of the work – like an echo connecting the pieces. I was also fascinated by some Italian artists like Marisa Merz, Gino De Dominicis, and Piero Manzoni, whose work I find very connected to poetry.

View of “Me, We,” Museion, Bolzano, 2023. Courtesy: the artist, ZERO, Milan, and Air de Paris, Romainville. Photo: Luca Guadagnini

View of “Me, We,” Museion, Bolzano, 2023. Courtesy: the artist, ZERO, Milan, and Air de Paris, Romainville. Photo: Luca Guadagnini

FT: The relationship between the visual arts and poetry has a very long history, even if the latter is not the textual modality that has prevailed in art discourse during the last century. In the best cases, art and poetry are both extremely synthetic “languages.” What kind of responses do you hope your exhibitions solicit from their publics?

S: I want my audience to feel free, to feel that there are many different paths. To be more specific, I want them to feel as if every cell in their body is opening up. I actually get into that state when I see good work: I am invigorated not only mentally, but also physically, and I believe looking at good artwork is one way I keep myself healthy.

FT: A certain attention to the outdoors and its generative possibilities is a recognizable feature of your work. What influenced you in this approach to art-making?

S: From the very beginning of my career, it was natural for me to think and present about my work outdoors. When I was young, it was a dream come true to show my work in a museum, but there were no established venues in Japan at the time where young artists could show their work. I think it is because of this that I am able to create works that are not limited to art museums and white cubes. I enjoy the changing conditions of the outside space, where the wind blows, the light changes, sometimes it rains, and sometimes birds fly in, and I like to realize my works in relation to these conditions. Sometimes I feel like I rely on the power of nature to create my work.

For me, art is never about showing off what I am good at, but always about discovering relationships: Let’s see what is happening!

FT: A work from the show that was highly appreciated – and shared – online, Bed Peace (2023), is a sculpture of two human-shaped figures lying on a bed, each made with materials from the soil of two different South Tyrolean valleys.

S: The initial title I had in mind was Honeymoon between Two Soils. I had the opportunity to show my work in a suite of a disused hotel in the Tohoku region of Japan, which I believe was used by honeymooners at the time, where I presented a work of the intimacy of dirt from two faraway places. When the work was done, it reminded me of John Lennon and Yoko Ono’s famous Bed-in performances at the Hilton Hotel in Amsterdam in 1969. It was a reaction to the Vietnam War, whereas in our day, there is Russia’s ongoing war in Ukraine; hence the title Bed Peace.

After making the human figures out of soil, I recalled the phrase “people die and return to the earth.” I think soil is a record of the people who have lived on and from it, even while it is still alive, receiving light and water, allowing grass to grow, and nurturing small insects and other living creatures. In this way, I often find myself making discoveries after I create something, and I believe that a work of art in which such things happen is a good work of art. For me, art is never about showing off what I am good at, but always about discovering relationships: Let’s see what is happening! Like the Surrealist motto “As beautiful as a sewing machine and an umbrella meeting by chance on a dissecting table,” I am interested in what happens after the chance encounter.

Shimabuku, Bed Peace, 2023. Installation view, Museion, Bolzano, 2023. Photo: Luca Guadagnini

FT: In a way, it’s like you’re creating the condition for something to exist and exceed the initial “surprise” value.

S: I’m part of the audience of my own work, I guess.

FT: Is this why you sometimes include animals?

S: Animals are creators that I cannot control. Some collaborations have been so interesting. Maybe I feel like Francesco felt.

FT: The saint of Assisi, you mean? Some claim he could talk to animals due to intoxication from a psychedelic weed, but I don’t think so.

S: Why should he have been on drugs? I think it’s quite natural to deal with animals. Shinto has made this relationship feel very natural in Japan. You can see that in a lot of animation, as you said. Maybe this was also once true for Europeans and simply has to be remembered.

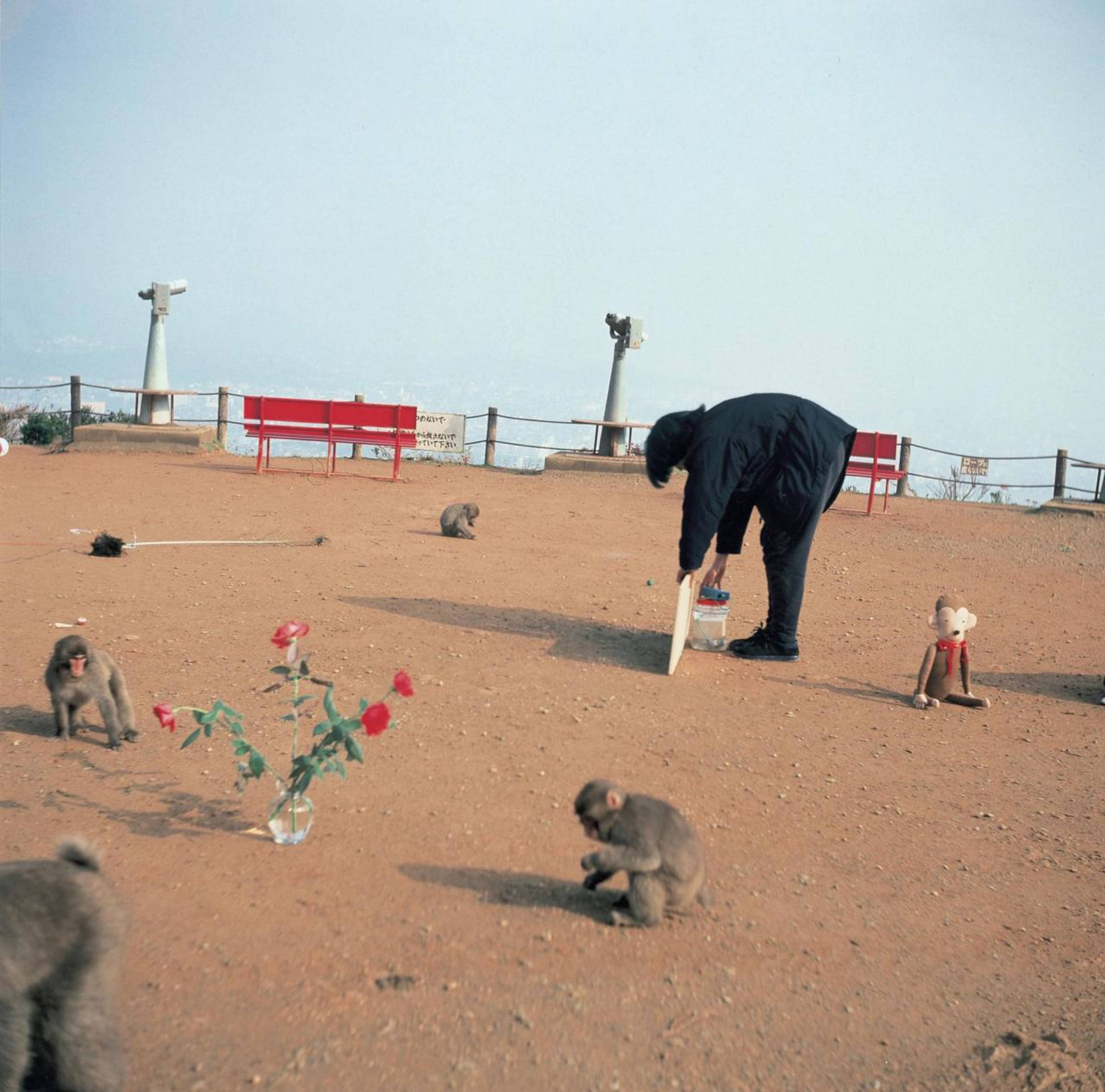

Shimabuku, Exhibition for the Monkeys, 1992. © Shimabuku. Courtesy: the artist and Air de Paris, Romainville

___

“ Me, We ”

Museion, Bolzano

6 May – 3 Sep 2023