Raimar Stange: Were you surprised that Candice Breitz’s exhibition in Saarbrücken was canceled?

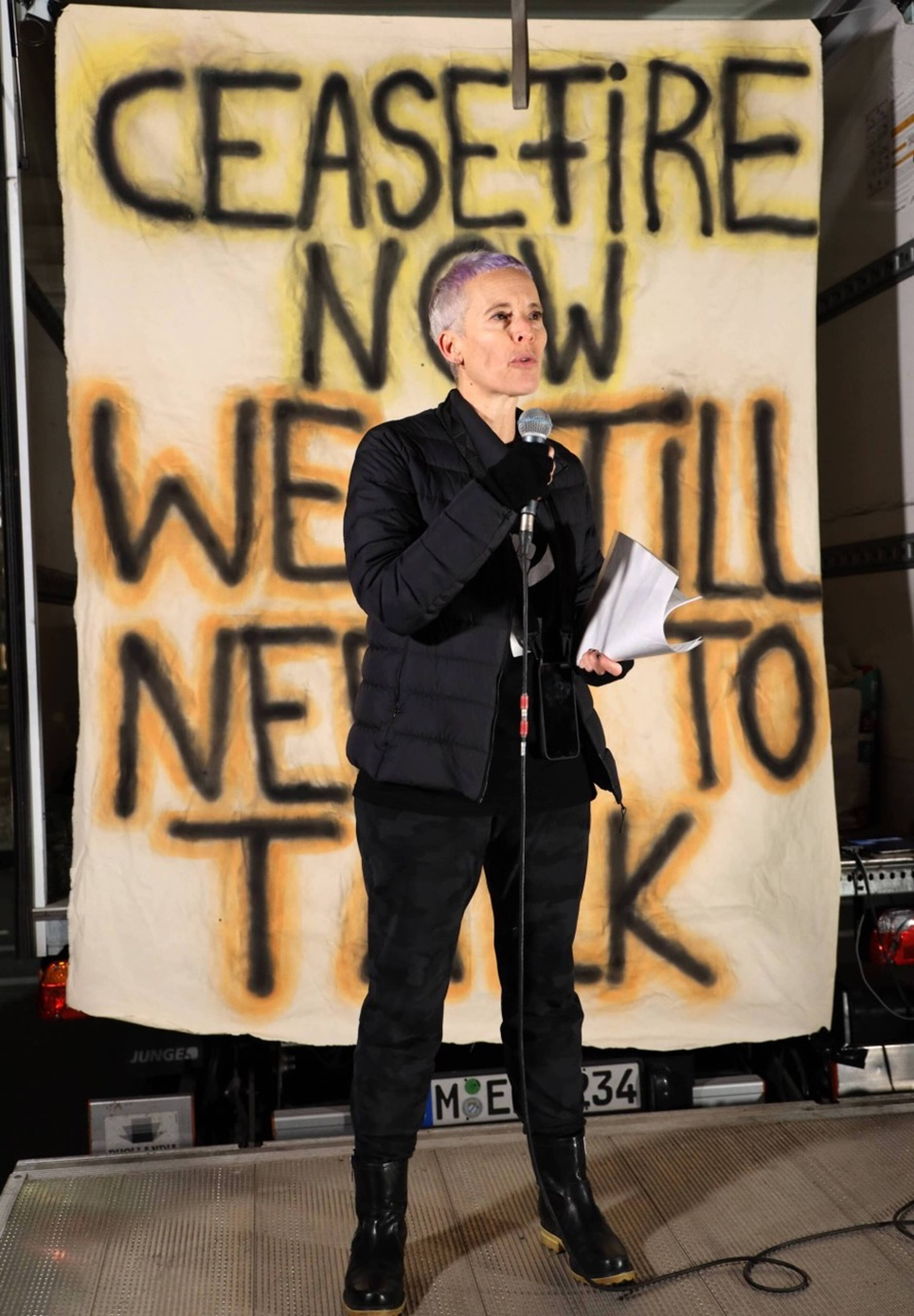

Alexander Koch: Yes, of course. I was astonished. Even today, I still can’t see how this cancellation could be legitimized. In the picture, though, it fits: Not a day goes by without people, performances, and projects being canceled or censored. Candice also experienced this when “We Still Need to Talk,” a symposiumon German Holocaust remembrance she co-conceived with the memory studies scholar Michael Rothberg, was canceled, first by the Berlin Academy of Arts, and laterby the Federal Agency for Civic Education. I wonder how much further these restrictions on freedom of speech can be ratcheted up. And this doesn’t only affect Germany. On Tuesday, the mayor of Paris stopped an event against anti-Semitism and its instrumentalization featuring Judith Butler and Angela Davis. So far, there hasn’t been a word about this in the German media[as of 10 December 2023].

RS: The Saarbrücken Museum rationalized what you call a“restriction of freedom of speech”by claiming, among other things, that Candice Breitz had not sufficiently distanced herself from the massacre Hamas committed on 7 October. Can you understand this justification in any way?

AK: No. Firstly, it is wrong; and secondly, it is completely exaggerated to accuse Breitz of not recognizing the “civilizational rupture” that 7 October supposedly represents. It is shameful that Germans are now explaining to Jews what they should feel and say about the murder of their fellow Jews. Candice has on many occasions explicitly and in strong emotional terms publicly condemned the Hamas attacks; it seems likely that people in Saarbrücken read an article that claimed otherwise. That is one of our main problems: Conjecture and insinuation alone are apparently enough to crack down, without first engaging the people concerned, checking facts, and putting forward solid arguments, which should be minimum requirements– especially for institutions – before censoring voices.

Most of the media are not doing any good for democracy at the moment. They seem sequestered in an apparent consensus that they think they should represent, but are themselves actually constructing.

RS: Dating back at least to documenta fifteen, and also in the context of the current conflict, the mere attribution of someone’s proximity to BDS [editor’s note: a worldwide, nonviolent campaignto use cultural boycotts, financial divestments, and state sanctions to pressure the Israeli state to abide by international law with respect to Palestine] is enough to result in penalties. Are we becoming victims of German’s Staatsräson (reason of state)?

AK: I would be careful with the term victim as long as many of the actors involved are (still) relatively privileged. This is where one has to start differentiating very precisely; it seems to me, then, that doing so should be the first virtue. There are human rights, basic laws, criminal codes, etc., which regulate quite a lot of what may be said and done. Yet, this common legal basis is beingundermined by moral claims and judgements. Artists do not have to submit to any reason of state. Period. Anyone who makes such demands is destroying common ground, just as anyone who wanted to enforce those requirements would probably be liable to prosecution. How much reason would remain in a state where that kind of coercion would be legal?

The BDS issue is complicated. However, as has been emphasized many times, a line is crossed when actions are retroactively criminalized and one’s “proximity” to that movement is assumed, which would first have to be precisely determined and proven on a case-by-case basis. To deny someone funding or a position because they signed a letter umpteen years ago in some other context reminds me of conditions that the German government criticizes in other countries, such as Turkey, where the mere insinuation that one is close to the Kurdish Workers’ Party (PKK) can lead to years of imprisonment. In Saarbrücken, people accused Candice of being close to BDS, even though such allegations have never been substantiated and she has never signed any of these letters.

Candice Breitz on the set of TLDR, Cape Town, October 2017. Photo: Sydelle Willow Smith

RS: Were someone’s proximity to BDS to be proven, would the state then have the right, according to the Staatsräson, to harass the person concerned? Doesn’t our freedom of speech also include the right to declare our support for a campaign that is not banned in Germany and that only a very few countries classify as anti-Semitic?

AK: What I mean is that the SPD, the Greens, the FDP, and the CDU/CSU introduced almost identical motions for resolutions in the Bundestag on 7 November to tighten the 2019 BDS resolution. They want to “strengthen the activities already directed against the (anti-Semitic) BDS movement to the effect that a ban on BDS activities or an organizational ban on BDS in Germany will also be examined.” If this development were to prevail, we would find ourselves in a situation that reputable authorities warned of in 2020 – a state boycott of actors and debates that can somehow be linked to BDS. We know that such accusations are easier to assert than to refute. Moreover, we know from our own history how state violence can creep up quietly and then swell into a regime. Things are already happening in Germany that make people in most countries around the world rub their eyes in disbelief.

RS: Is one of those things a press landscape where leading media criticize pro-Palestine initiatives, but are virtually silent about the cancellation of Candice exhibition? Are our media increasingly organs thatenforceconformity on themselves?

AK: I am keenly aware of how many of us are looking for terms that can describe what is going on. I think that part of the epochal change we are undergoing is that, while our old vocabulary only fits to a limitedextent, a new vocabulary has not yet been established. People are outraged and upset, but when they want to make clear statements, they get stuck. Enforced conformity: It feels like that, yes. In any case, most of the media are not doing any good for democracy at the moment. They seem sequestered in an apparent consensus that they think they should represent, but are themselves actually constructing. In an anticipatory domino effect, they mutually reinforce their own positions without sufficient feedback from the outside world, from society. As a result, many intelligent people no longer have a platform. They are neither asked nor heard from, because they could and would say something that doesn’t conform.

Democracy means conflict, and that’s what you get when there are different opinions. It seems that people in Germany have completely forgotten that.

RS: That has consequences ...

AK: I wonder: Minus most AfD voters, perhaps seventy percent of the rest of the population would agree with much of what you, Candice, or I think, provided information and arguments were exchanged. Maybe I am wrong. But what if I’m not? Then, the crisis of representation would be even greater than we already think, also in the media. This includes the fact that, in line with politics, terms like apartheid or genocide, as well as some BDS demands, are immediately described as illegitimate or even anti-Semitic, regardless of whether international Jewish organizations or the UN use the same words or make the same demands. You can criticize this harshly,but democracy means conflict, and that’s what you get when there are different opinions. It seems that people in Germany have completely forgotten that.

RS: To return to Candice’s show: You are being asked on social media to sue the Saarland Museum, as the cancellation has economic and reputational consequences. Will you sue?

AK: I think that, from now on, individuals and various entities – institutions, galleries, publishers, et al – should increasingly consider whether they have legal recourse if they are hindered in their respective practices; if they are exposed to defamation of character; or if the state or media organizations discriminate against or delegitimize them. It would be important that they not fall unchallenged into the victim role you mentioned. But only a few people can afford to do that. After all, we have energetic lawyers in the country, many of whom admire art and value freedom of speech. I would very much welcome it if an alliance of art- and law-lovers were formed to intervene in places that are systemically relevant, specifically when the cultural actors concerned cannot afford such a process themselves. This would then require the support of third parties. It’s not about the individual case. It is about fundamental rights and, increasingly, attempts to undermine these rights. In a democracy like ours, those rights belong to all of us.

Candice Breitz, TLDR, 2017, thirteen-channel video installation. Photo: Sydelle Willow Smith

A version of this article, “Die Kampfansage,” was first published in German on 10 December 2023 at artmagazine.cc

___