“... I saw my world through my double lens; it seemed everything had broken but that.”

– Joan Jonas in Lines in the Sand, 2002

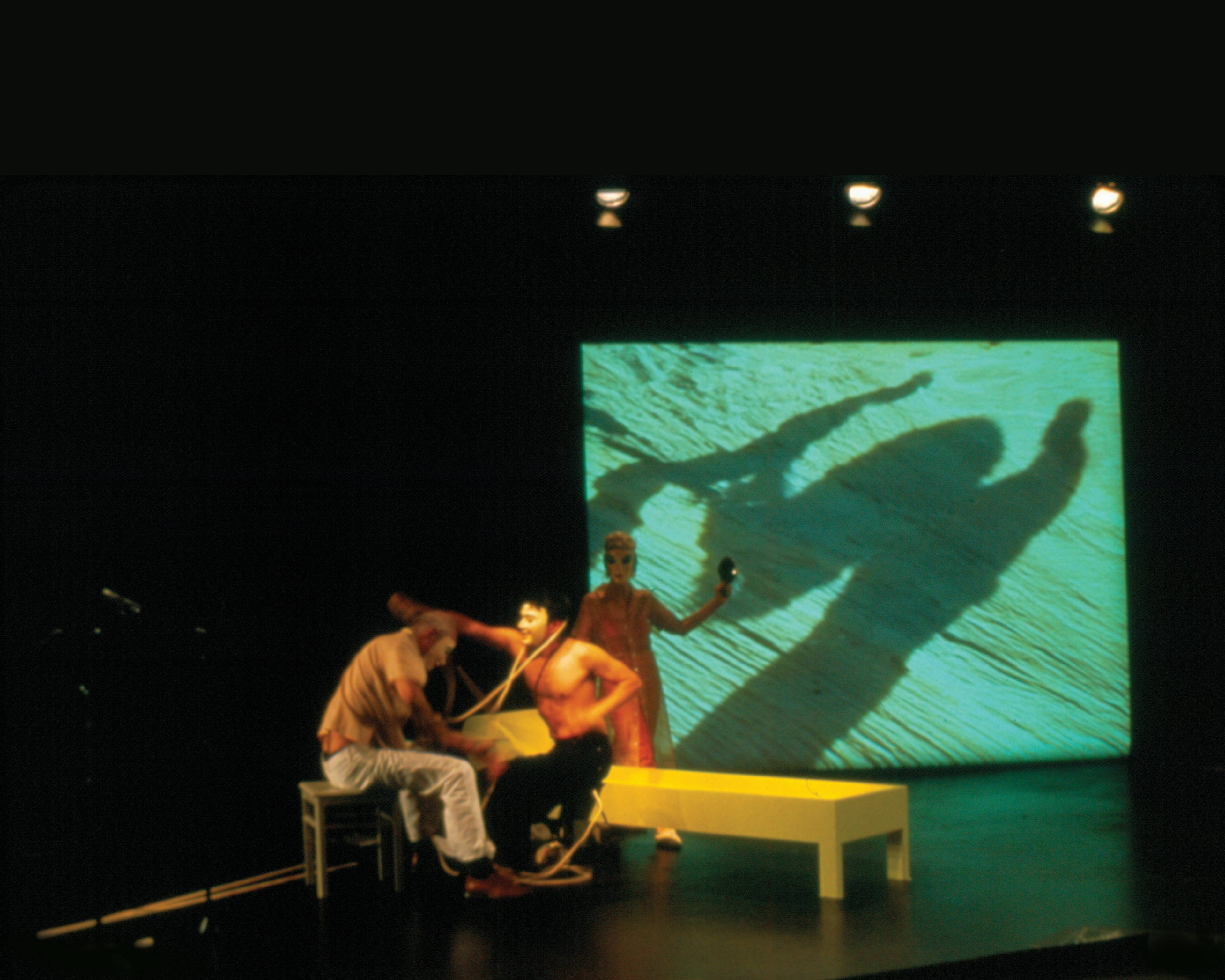

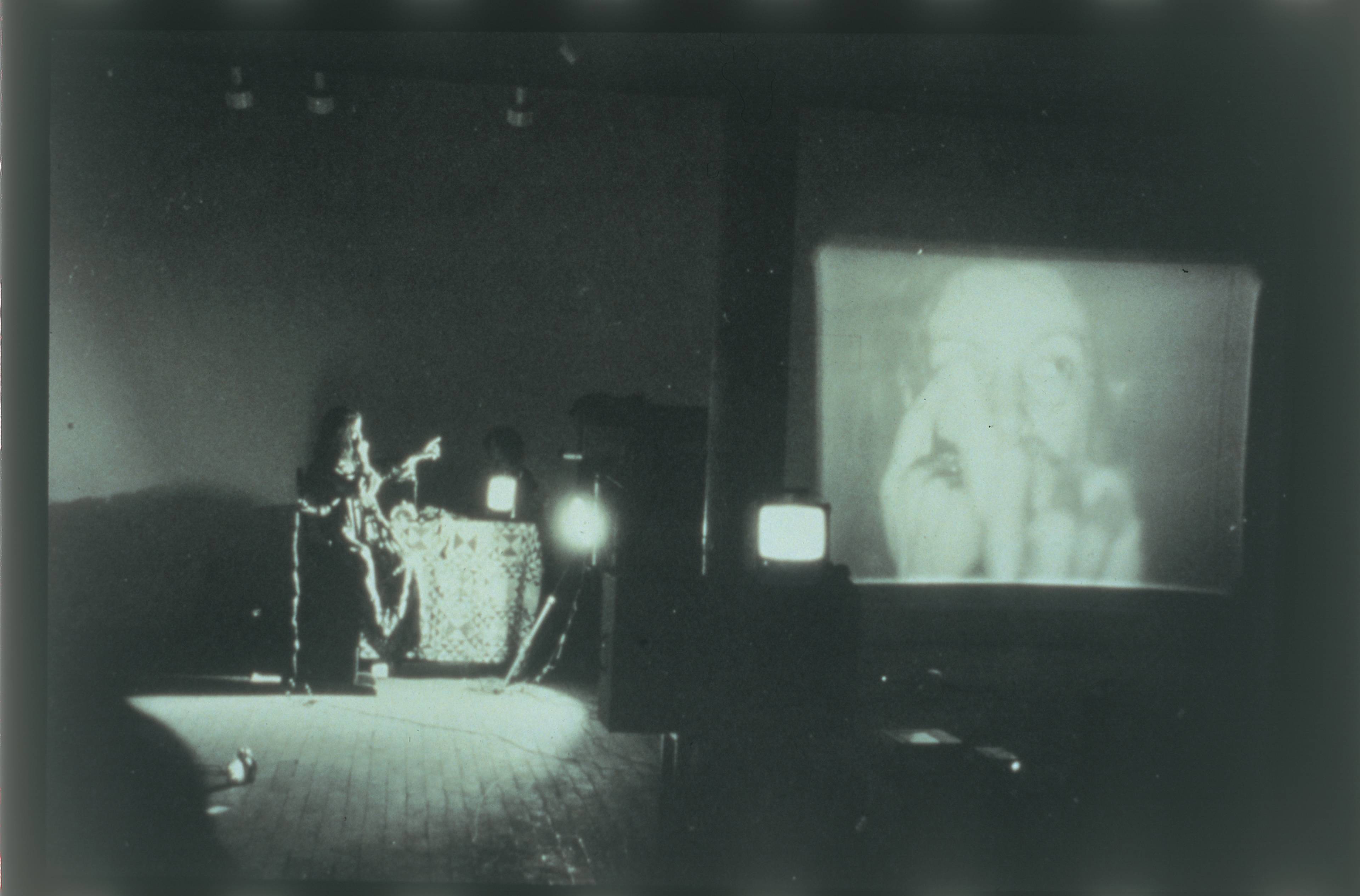

A petite woman with gray-white hair slips across the stage on light feet. Her eyes are bound with a transparent veil, something like a mask. She looks up, circles around, and begins to speak. She can see everything, but we cannot see what she sees. Two men and two women, alternately wearing masks, move in couples and film what is happening with a video camera, so that it is transferred simultaneously to the video screen in the background. Jonas and her actors recite textual passages spontaneously, and sometimes simultaneously. The stage set for the performance seems to be a randomly scattered collection of masks, Ytong blocks, rods, sand, trays, and all sorts of everyday objects. Video pictures of Jonas dancing in the studio with her dog Xena, shadows on the beach, and old photos from Egypt, but also of building sites and gambling casino settings from Las Vegas, fill the room as a source of light. Text, image, places, and times merge into each other. It is the world premiere of the Joan Jonas performance Lines in the Sand at Documenta 11 in July 2002.

Lines in the Sand deals with the myth of Helen. Everything began with photographs from 1910, taken in Egypt by Jonas’s grandmother, the epic poem Helen in Egypt (1961), and the autobiographical text Tribute to Freud (1956), both by the American poet HD (Hilda Doolittle). Helen, the world’s most famous hostage, leaves Greece during the war against Troy but never leaves her first stopping-off point, Egypt. Helen was never in Troy.

Lines in the Sand, 2002, performance documentation, Documenta 11, Kassel. Photos: Werner Maschmann

As absence, as fiction and fantasy of a frustrated male need, and as simulacrum, she becomes the triggering factor for the biggest trade war in the ancient world. Jonas here takes the events of 11 September and the US attack on Iraq as her sub-texts in order to discuss the topicality and the repetition of history and the images constructed for it. And indeed, shortly after 9/11 both a TV series and a Hollywood blockbuster brought the eternally popular topic of Troy to the American and European markets.

“There was something that was beating in my brain; I do not say my heart – my brain. I wanted it to be let out. I wanted to free myself of repetitive thoughts and experiences – my own and those of many of my contemporaries.”

– Joan Jonas in Lines in the Sand, 2002

Lines in the Sand is also to be seen as part of a total work that constantly renews itself and adapts and changes to suit the locality of the performance. There is no defined construct according to which the installations and appearances – in Kassel, Mexico City, Miami, Chicago, New York, Paris, London, or Taipeh – can be oriented. Rather, her presentations pursue myriad displacements both geographical and personal, sometimes ironically, sometimes seriously. Jonas brings the thread of Sigmund Freud’s encounter with the myth of Helen in Lines in the Sand forward to her new work complex, The Shape, the Scent, the Feel of Things. The starting point for this work is Aby Warburg’s visit to the Pueblo Indians in 1895 and his resulting text Snake Ritual (1938), its relationship to Freud, and the settlement of the American West. After an installation version at the Renaissance Society, Chicago (2004), The Shape, the Scent, the Feel of Things was seen for the first time as a performance at Dia:Beacon New York in October 2005. As “Work in Progress” it was not the re-telling, but the layering, not explaining,but casting doubt that stands at the centre of Jonas’s oeuvre.

The Shape, The Scent, The Feel of Things, 2004. Installation view, The Renaissance Society, Chicago

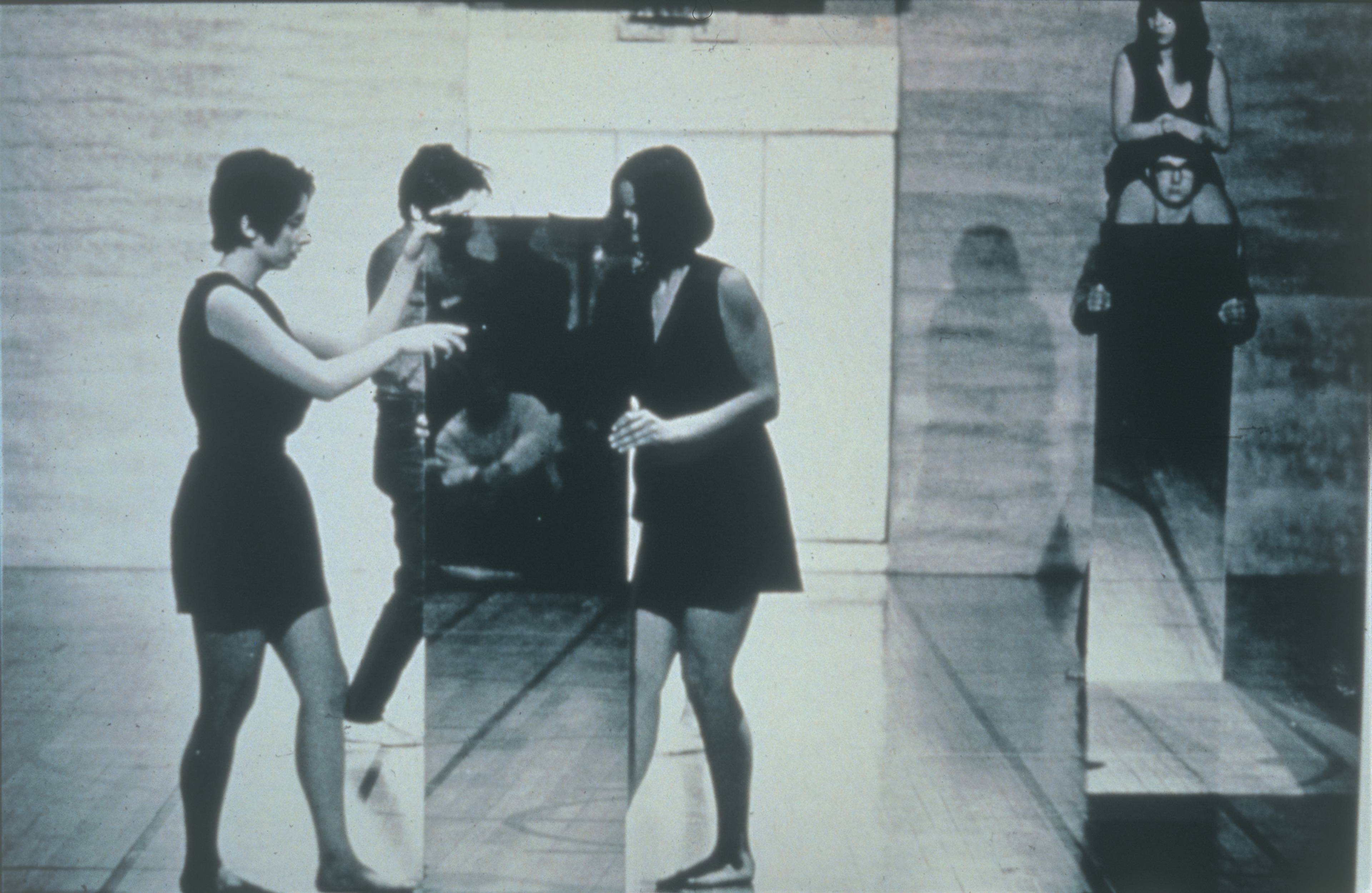

Mirror Piece II, 1970, performance documentation, Congregation Emanu-EL, New York. Photos: Peter Moore

“In many respects, the death of metaphor – something for which minimalism proudly claimed credit – was in fact the birth of performance art as the body became a literal rather than metaphoric agent in the enactment of meaning … Dissolving sculpture and performance in a rigor attributable to minimalism, Jonas forged a hybrid but singular vocabulary from two distinct and disparate disciplines at a moment when vigilance regarding medium specificity should have kept them separate.”

– Hamza Walker on “Joan Jonas, Lines in the Sand and The Shape, the Scent, the Feel of Things,” Chicago Renaissance Society, Chicago, 2004

The factual origins of Jonas’s artistic practice are in her concern for archaeology, anthropology and folk cultures, visual and applied arts, painting, history, and literature. After 1958, while she was still a student of art history and sculpture, she undertook long journeys to Greece and Turkey. She visited the reserves of the Hopi Indians in the southwest of the United States, travelled through Japan from 1970, where she also bought one of the earliest Sony Portapak video cameras. Her absorption in cultures that were foreign to her is the basis of her reflection on her “own” culture. As a parallel to her development of “sculptural” performances there, are self-presentations and roleplays at the center of her work. In them, she deconstructs and reconstructs the role of the artist as author and myth and the meaning of an artwork as a commercial item and an object of desire.

Nova Scotia Beach Dance, 1971, performance documentation, Halifax, Canada. Photo: Richard Serra

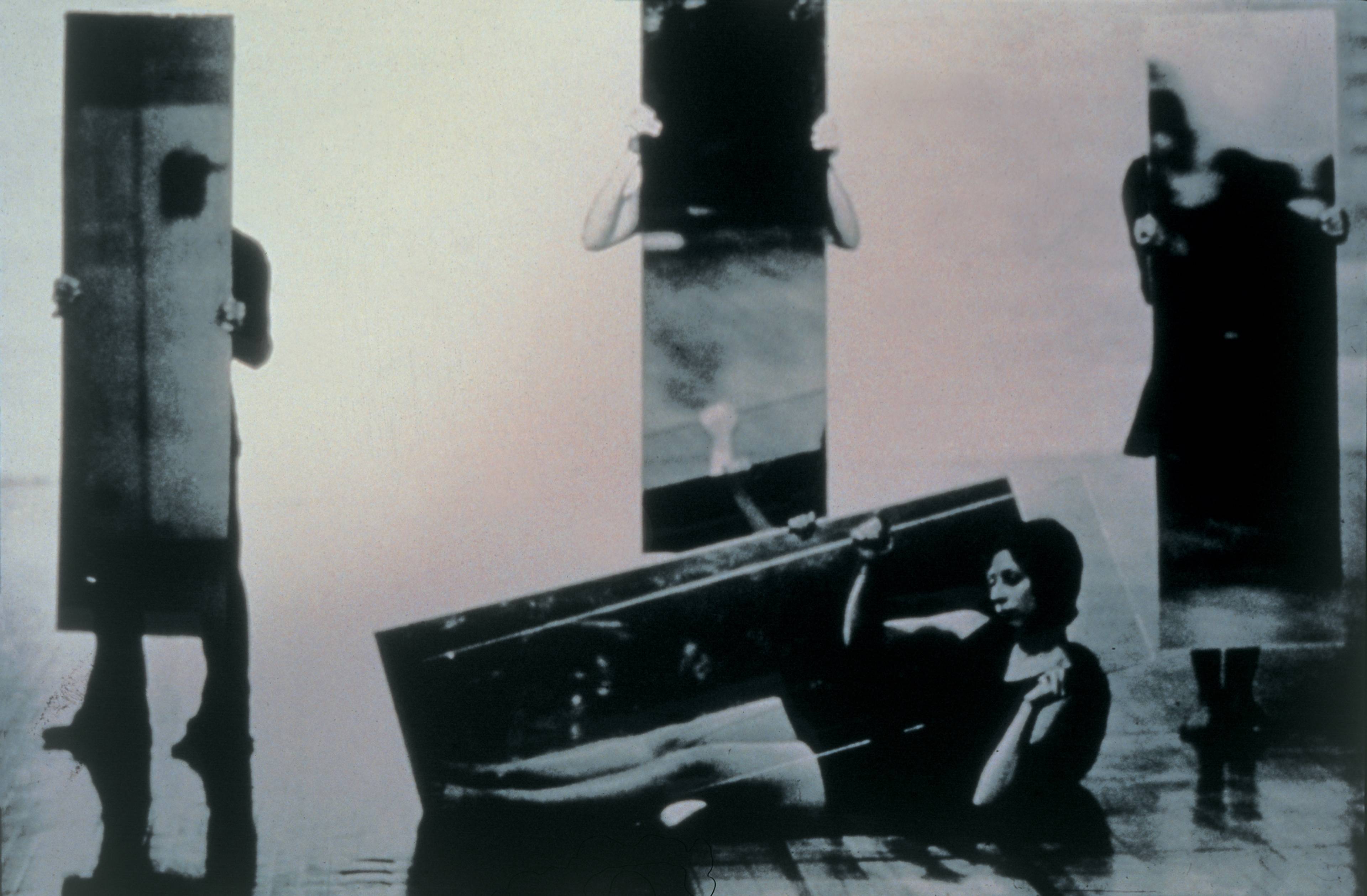

Delay Delay, 1972, performance documentation, New York. Photo: Gianfranco Gorgoni

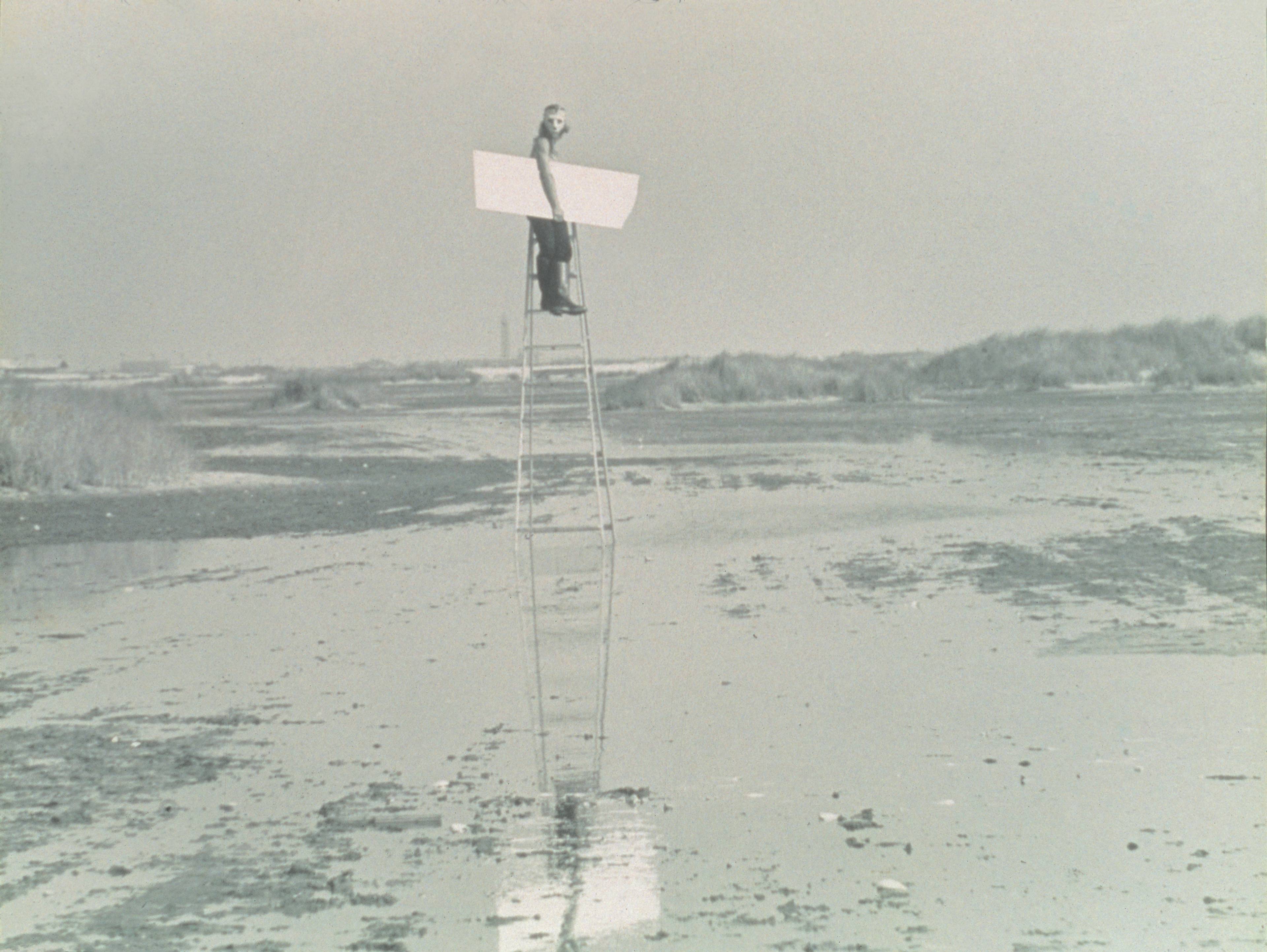

Jones Beach Piece, 1970, performance documentation, Long Island, New York. Photos: Richard Landry

Her productions, influenced in their simplicity by the minimalist dance of Yvonne Rainer and Robert Morris (Judson Dance Theater), took place in the deep construction site of the World Trade Center or on the beaches of Long Island or of Nova Scotia, Canada. The landscape and the city were the setting and the theme in such performances as Mirror Piece I & II, Jones Beach Piece (1970), Nova Scotia Beach Dance (1971), and Delay Delay (1972). In this phase, Jonas developed an emblematic vocabulary from a synthesis of ritualized gestures, which is still essential to her work today. She blended dance elements from the Japanese No and Kabuki theatre, Mediterranean wedding rites, and the dances of the Hopi with the aesthetics of video images, the gesture of drawing, and elements of sculpture. The core pieces of Jonas’s artistic language are symbolic objects, whose language of forms ranges from simple blocks and geometrical figures to found and self-made masks, costumes and toys.

“The audience sees, in fact, the process of image-making in a performance simultaneously with a live detail. I was interested in the discrepancies between the performed activity and the constant duplicating, changing and altering of information in the video.”

– Joan Jonas on Organic Honey’s Vertical Roll (1972)

Around 1970, Jonas’s innovative integration of mirrors and the new medium of video in performances that now took place indoors made her one of the leaders in her genre, alongside Vito Acconci and Bruce Nauman. The success of the video medium in her art was first based on its potential, in contrast to film, to present its images simultaneously on monitors and projection walls. Live feed on the stage was discovered.

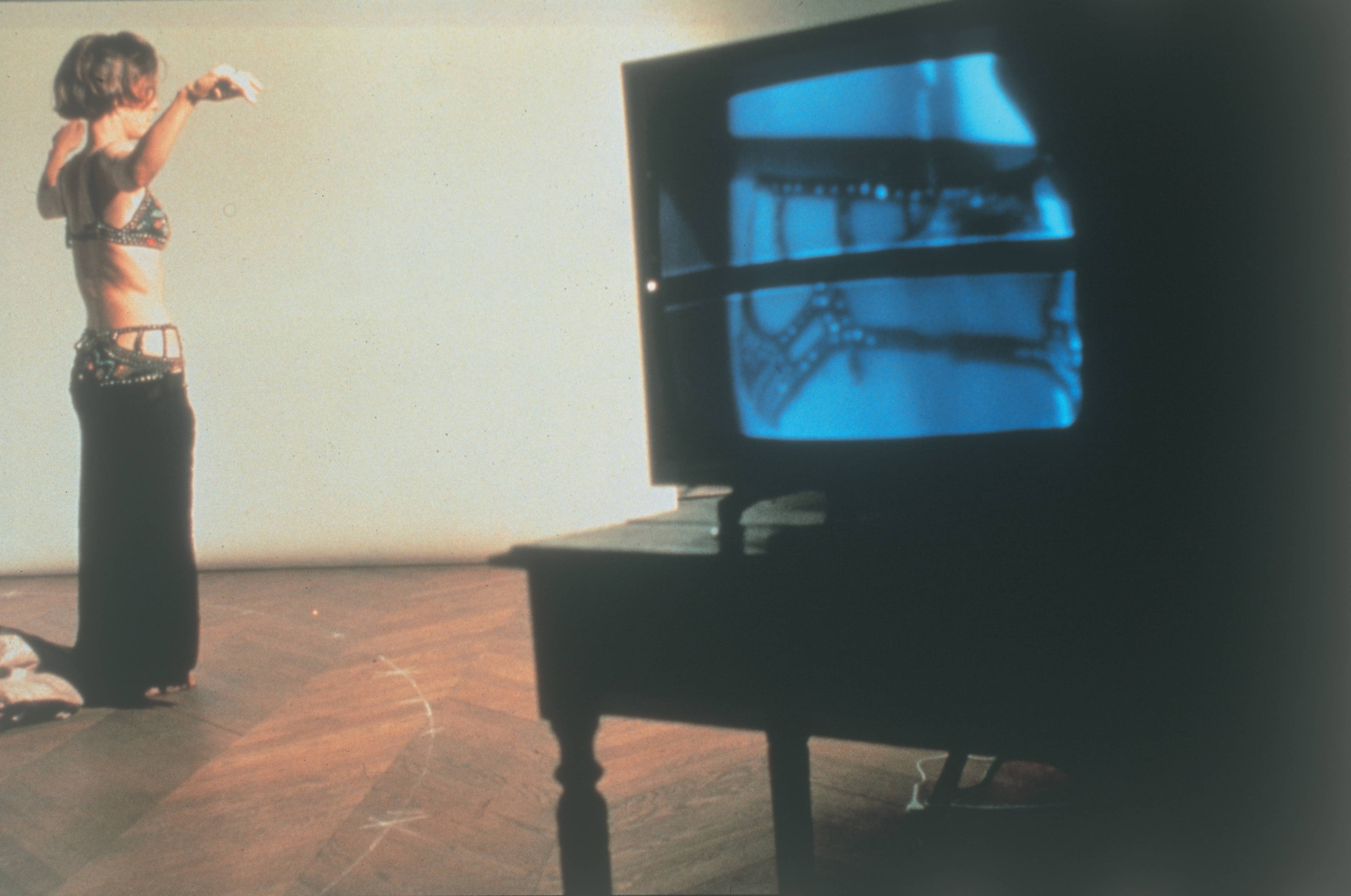

Organic Honey’s Vertical Roll, 1972, performance documentation, Musée Galleria, Paris, 1973. Photo: Beatrice Helligers

Organic Honey’s Visual Telepathy, 1972, performance documentation, Loguidice Gallery, New York. Photo: Peter Moore

Babette Mangolte and Joan Jonas, Organic Honey's Vertical Roll, 1972, performance documentation, Musée Galleria, Paris, 1973. Photo: Beatrice Helligers

By means of live feed, viewers were in a position to perceive Jonas’s gestures as simultaneously real and reproduced. By mirroring and multiplying herself, she developed the persona of the electronic magician Organic Honey. In the video performances Organic Honey’s Visual Telepathy and Organic Honey’s Vertical Roll (1972), Jonas became the protagonist of her self-presentation and the medium for showing constructions of the feminine. With her presence and her de-synchronized series of movements, Jonas questions herself in the reflection of her own position as both artist and picture. From the end of the 1970s, she used her own language of drawing and gesture to process sound, music, and texts from folk stories, mythology, and literature. Here she broke up the imaginary stories and traditional gender polarities that dwell inside these stories and myths, from the brothers Grimm to Icelandic sagas. In the performance Variations on a Scene (1990), which took place on the bed of the Hudson River Valley, or the Irish epic of a warrior condemned to be a bird as a social outsider, … Sweeney Astray (1994), she slips into the narrations and figures of other works. Jonas makes visible the impossibility of understanding a/the/her story in all its aspects.

By doubling up and splitting her heroines, as in the myth of Helen in Lines in the Sand or the Icelandic goddess Gudrun in Volcano Saga (1985–87, played by Tilda Swinton), she opens to the process nature of art and the construction of myths to experience. Jonas creates a mass of information, images, gestures, and objects, which unfold before the viewers’ eyes into a multifaceted event. In 1982, the American art historian Douglas Crimp characterized this performative method of deconstructing perception and illusion, anchored in the widest range of real and fictitious stories, figures, and spaces, with the concepts “De-Synchronization“ and “De-Centralization.” Meaning: a production without a hierarchy of design, a formal center, or a narrative climax; a kind of all-over effect of performance art, which makes Jonas’s work completely topical in the interaction of physical activity, media transformation, and spatial presence.

– Translated by Nelson Wattie

Volcano Saga (Detail), 1985–1987, performance documentation, The Performing Garage, New York. Photo: Gabor Szitanyi

Revolted by the thought of known places … Sweeney Astray, 1994, performance documentation, Westergas Fabriek, Amsterdam. Photo: Joan Jonas

Variations on a Scene, 1990, performance documentation, Wave Hill Bronx, New York. Photos: Joceleyn Lee

___

“Joan Jonas: Good Night Good Morning”

MoMA, New York

17 Mar – 6 Jul 2024