“After Laughter Comes Tears” is like a pop song: affable, ephemeral, garish, executed with a high-production value. And like a pop song, it is in-your-face. Its curatorial frame intends to tackle how “our bodies and minds react and cope with the drama we are currently living through. What is capitalism doing to them?” The show answers by way of exhibiting thirty-four artists through a four-act setup (with prologue, epilogue, and interlude), making the ephemerality literal: Each chapter activates only specific artworks that cohabit the two big halls of Mudam, turning on screens, setting installations in motion, and spotlighting static ones.

The first, titled “Sick, sad world,” like the edgelordy tabloid show that MTV’s sitcom star Daria watched on cable, observes our state of affairs as if through her sardonic, disconsolate eyes. Isaac Lythgoe’s (*1989) glossy bronze sculpture I don’t remember anything you said to me last night (2022) imagines two Bambis calling each other. They actually fail to do so, the strands of two démodé rotary phones entwined on the ground. Cute, uncanny, sort of extra-terrestrial, the puppyish deer stand opposed as if ready to fight, hinting at how childish, alien, and polarized communication looks these days.

View of “After Laughter Comes Tears”

And yet, “Talking Is Not Always the Solution,” as Omer Fast (*1972) titled one of his shows (at Berliner Festspiele in 2017). His CNN Concatenated (2002) faces Lythgoe’s fawns. On a low-def television, one anchorperson replaces another, then another, then another, each time a little too jittery. Deconstructed and recast from 10,000 CNN news clips from before, during, and after 11 September 2001, the video voices a sentimental monologue one word at a time: “I / just / feel / I / have / so / much / to / give / but / sometimes / you / can / be / so / full / of / resentment.” “Why / is / that?” “Perhaps / I / talk / too / much.” An omen of our emotion-based, post-truth mediascape.

The show’s second act, “Crisis mode: on,” portrays a response to our “global drama” that is tentative, unripe, and occasionally gauche. In Artur Żmijewski’s (*1966) video Temperance and Toil (1995), a young woman and man, both naked, push and pull and press each other’s bodies like infants in their sensorimotor stage – discovering the difference between themselves and their environment. He kneads her face like Play-Doh, she pushes him under her armpit as if to swallow him. Should we unlearn the codes of the body to become better endurers? And why should intimacy be reflexively sexual?

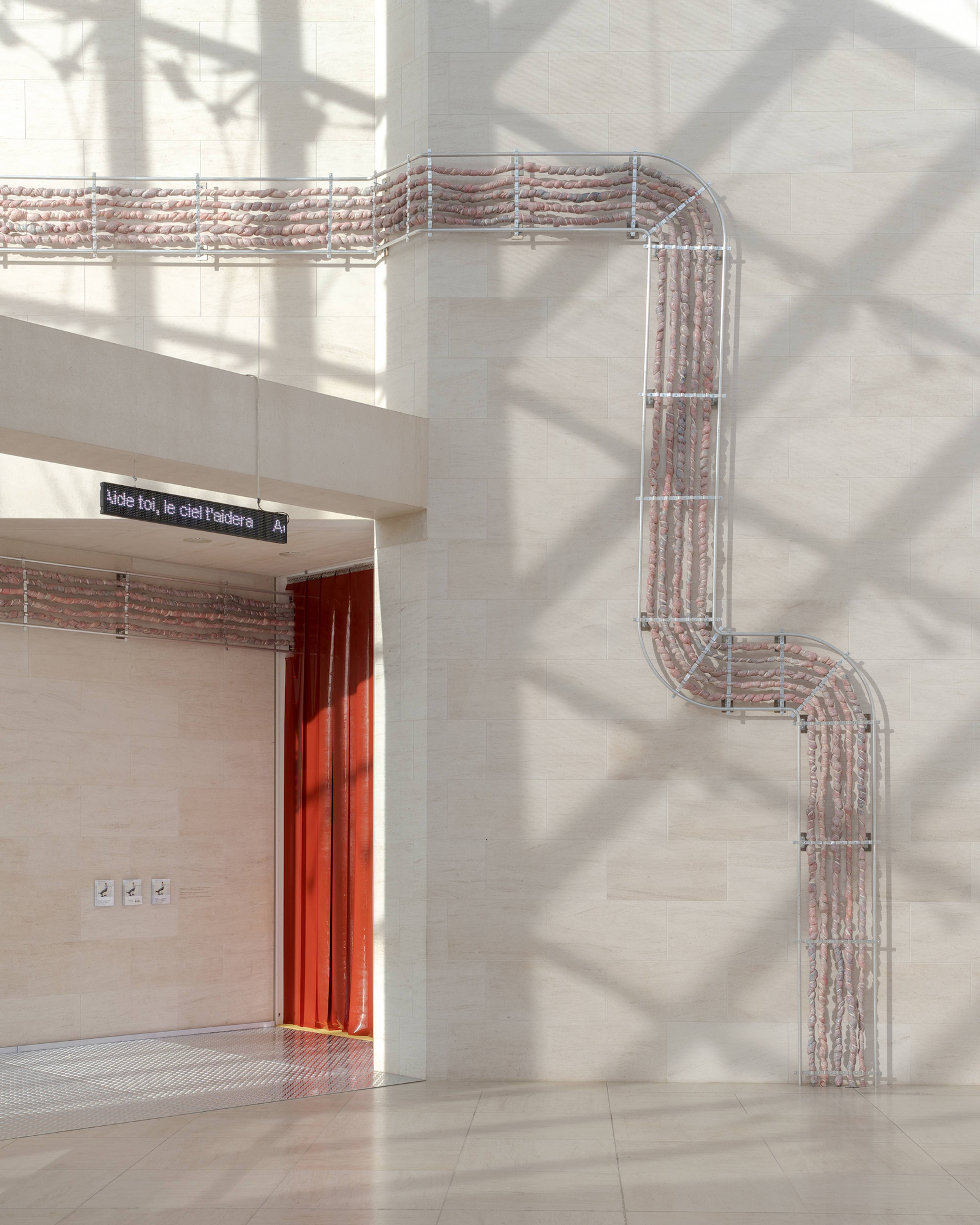

Chalisée Naamani, Maison Sac à Dos ou Habit(acle), 2020. Installation view, Mudam Luxembourg, 2023

View of “After Laughter Comes Tears”

Right behind, in Stine Deja’s (*1986) Assembly (2022), a group of people cling to each other in a metal ring, with heads for speakers, all wearing orange safety jackets. They huddle together tightly, but cannot see, hear, or move; they are only able to ask and reassure themselves in chorus: “Are we going to be okay? We’re okay. Are we going to be okay? We’re okay …” In the face of crisis, we risk taking the shortcut of IRL Discord channels – invite-only communities of like-minded people and deterministic solidarity – and getting stuck, closed off to debate.

What if all this attention to care is a bluff, the third act, “Aide-toi, le ciel t’aidera” (Heaven helps those who help themselves), seems to ask. Mungo Thomson (*1969) answers with Volume 2. Animal Locomotion (2015–22), a stop-motion of illustrations from Time-Life Books’ twenty-volume series “Fitness, Health and Nutrition” (1987–89). Well-set men’s and women’s bodies run, row, stretch, and lengthen at an inhumanly rapid rhythm, soundtracked by computer-music pioneer Laurie Spiegel. One of them does the session in white-collar attire, directly on his office stool. Is physique-streamlining turning us into unbreakable work machines? Nearby, Monira Al Qadiri (*1983) responds with Deep Float (2017), a claw-footed bathtub whose bather seems to drown in pitch-black petroleum. Before becoming fuel, oil was an ancient therapeutic, a “miracle liquid.” How many tonics has human history turned toxic? How many do we not yet spot?

View of “After Laughter Comes Tears”

The last chapter, “Tears dry on their own,” makes for a darker, more disruptive cadenza. Pauline Curnier Jardin’s (*1980) Qu’un sang impur (Bled Out, 2019) recasts the young, muscular inmates of Jean Genet’s homoerotic Un chant d’amour (A Song of Love, 1950) as menopausal German women. Half lustful, half disdained, the grannies eye-ball young men who cross their paths and, just before killing each of them, ooze menstrual-pulp rivers, then auto-erotically explode in their prison cells. Why, indeed, shouldn’t the end be the most self-respecting chance for reclamation, for a spasm of liberty and no more shame?

As the exhibition’s epilogue, three banners from Chris Korda’s (*1962) anti-natalist Church of Euthanasia – which, since 1992, has proposed population reduction as a solution to the environmental crisis – hang on the exit door. One reads: SAVE THE PLANET KILL YOURSELF.

“Saying you have a political solution is like saying you can write a pop song that’s going to stay at the top of the list forever,” cyberpunk author Bruce Sterling once said. Rather than try, “After Laughter Comes Tears” answers a too-big question with a bold, maximalist, consciously naïve spirit. Like a summer hit, it might be pesky, but there must be a reason why so many of the thirty-four refrains do hook. Perhaps, as earworms, they vocalize a need for something we don’t like to acknowledge.

Jean-Charles de Quillacq, bébé, 2023. Installation view, Mudam Luxembourg, 2023

___

“After Laughter Comes Tears”

curated by Joel Valabrega and Clémentine Proby

Mudam, Luxembourg

13 Oct 2023 – 7 Jan 2024