The work of the pseudonymous Lutz Bacher (1943–2019) speaks in escape clauses, smokescreens, and broken promises. At the lip of a void, the glaring hole of Bacher’s presence was only ever partial; from the mid-1970s, her attitudinal work throbbed with XXL opacity and a lick of seduction. Through intimate surrogacies and sly reverses, Lutzian antics situate the viewer among the unanswerable, the ineffable, and the unsettled. Elusiveness underwrites her endgame: To trace consistencies in her conceptualism is to see the work disperse into affective excess. In Bacher’s oblique way, things are blown open.

And so, at “AYE!,” curated by Anthony Huberman and initiated with the artist before her death, we’re left among dispersions and digressions of threshold moments. Conceived as a meditation on Bacher’s use of music, voice, and sound, we infer what she leaves behind through disembodied expressions, their suspended refrains at Raven Row by turns dissonant, cosmic, and soporific.

The Book of Sand, 2011–12 and What Are You Thinking, 2011. Photo: Anne Tetzlaff

In the whiteout of snow is where so much psychic slippage plays. “What am I doing in this stereoscopic dreamland?” asks Nabokov in Speak, Memory: An Autobiography Revisited (1951), alone in the snow: “The snow is real … as I bend to it and scoop up a handful, sixty years crumble to glittering frost-dust between my fingers.” Decades lost in a fistful. In Bacher, snow, sand, smoke, and stardust evade scrutiny with their shifty metaphorical potential and vast psychological terrains.

The eponymous video What Are You Thinking (2011) samples audio from Philip Kaufman’s 1988 film adaptation of The Unbearable Lightness of Being. “I’m thinking how happy I am,” a voice issues, amid tinkling piano keys and the white noise of rainfall. The recording plays across four monitors whose grayscale blurs blaze and disappear loop by loop. The work is installed upon The Book of Sand (2011–12), its carpet of lunar-blonde powder slowing and deferring the contact of each step, further hollowing out any sense of intimacy and displaced sentiment. Poised between two negatives, Bacher’s bait of “happiness” is a self-evacuating decoy, permitting metaphor to roll in like dry ice.

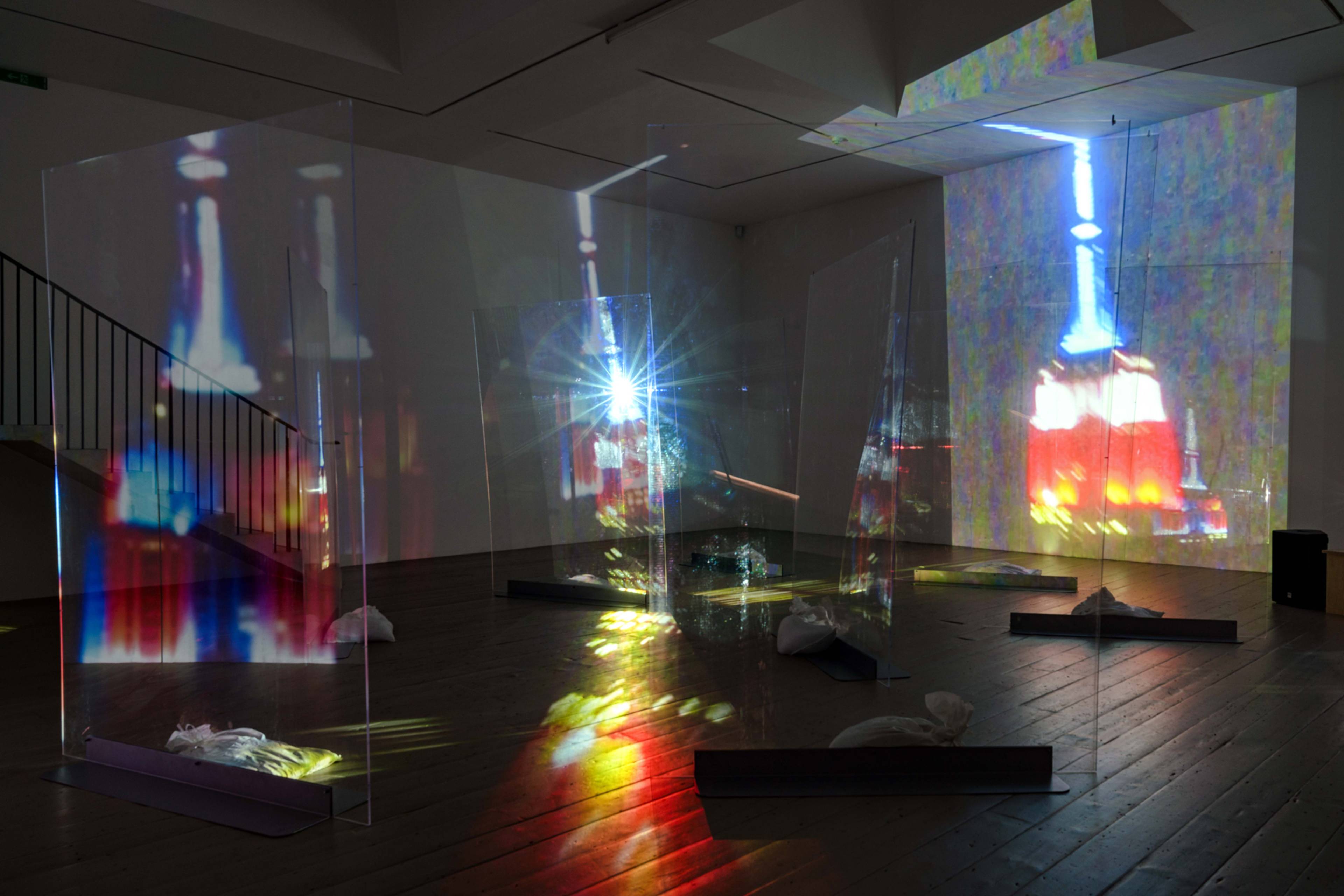

Empire, 2013. Photo: Anne Tetzlaff

Yamaha, 2010. Photo: Marcus J Leith

Delivered with cool, seemingly impersonal economy, the stultifying climate of the first gallery switches to an intoxicant pitch in Empire (2014). In a droning digital projection, the Empire State Building wavers dazedly across numerous sheets of plexiglass anchored by sandbags, its nauseous edifice less architecture than a perfunctory image of red-white-and-blue nationhood. Empire repeatedlydenies the monument power, pulling it back to a state of inertia and semiotic breakdown, its orchestrated, orchestral fallibility an occasion to ambush the viewer. In Yamaha (2010), a mechanized organ auto-plays notes that consistently misfire, each error scare-quoting the affect of music and reifying the militarization of rhythm. Like Empire, however, Yamaha deflates any contrivance of majesty, its architecture of titanic, rusted organ pipes precariously balanced like a pyramidal nest of deactivated projectiles.

Upstairs, Magic Mountain (2015) forms a literal, Berg-like buffer, its glacial mass of punk-stud audio-foam peaks disabled as absorbers of juggernaut sound. As what establishes a shell or border is fleshed out into a subject, material configuration assumes alluring depth. The impenetrable ravines of this mute massif engulf the attention, its looming scale drawing the eye into darkened crevices that lead to obscure dead ends. Magicking up a fiction from the mundane real, her mountain is a loss of grounding; it can’t, though, incorporate the needy resuscitations of Leonard Cohen in PLEASE (LC) (2013–15), installed in an adjoining room. In this four-channel video projection, the singer is all melancholy, pleading interminably amid a roiling, Lynchian blue. Chords overlapping in woozy disharmony, Cohen’s eight-fold processed vocal hovers between the metronomic and the incantatory, its sonic exhaustion an aberrant measure of time.

Magic Mountain, 2015. Photo: Anne Tetzlaff

Nearby, a stammering choir of radios layer and loop a fragment of Roberta Flack’s 1973 version of “Killing Me Softly with His Song,” the vocal – which plays across a pirate FM radio signal – casting a voluptuous, pre-verbal note of emotion made incorporeal. In these glitchy exposures, Bacher’s trance-y sensual overloads and elliptical displacements coax latent interiority out of the echoes of others, arresting constitutive moments and brokering connection. To me, that sounds like listening.

The amplification of subtraction occasions Bacher’s big, inviting distortion, where somatic intensities are awakened within states and structures of betweenness. In these lossy vibes, where technical degradations duplicate, dilute, and dislodge material – apparently “losing” quality – one finds Bacher’s additive, “good” corruption. In her parafictive, dayglo conceptualism are these enigmatic textures of desertion – if she once described her work as “one big ruin,” its rubble here is the messy territory of unadulterated mood.

KMS, 2016. Photo: Anne Tetzlaff

___

“AYE!”

Raven Row, London

5 Oct – 17 Dec 2023