Am I wrong to detect a delicate ambivalence in the Fondation Louis Vuitton’s presentation of Joan Mitchell’s work? The Chicago-born painter lived in France from 1959 onward, yet has always been known as a “New York School” Abstract Expressionist. In retrospect, she has become the most renowned of that movement’s second generation – which also included Norman Bluhm and Al Held – who were overshadowed in their day by seemingly more radical contemporaries like Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg. In 1967, she purchased a property at Vétheuil, where Claude Monet briefly lived, and not far from Giverny, where he maintained his legendary gardens, residing there until her death in 1992. That her art represents an emotional response to landscape has been crucial to its reception, such that pairing Mitchell and Monet is intuitive. Yet while she apparently appreciated being compared to Monet – what painter wouldn’t? – she found the comparison facile, based as it is on mere geographical proximity and a shared interest generally in landscape. That tension is evident in Paris, where a large Mitchell retrospective that toured San Francisco and Baltimore to great acclaim is eclipsed by Suzanne Pagé’s juxtaposition of the painters in “Monet – Mitchell,” which, while perhaps certifying her Frenchness to broaden her local appeal, leaves Mitchell playing second fiddle to the beloved Impressionist.

View of “Monet – Mitchell,” Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris, 2022

But that word, Impressionist, is precisely the one that a deep view of the art of Monet’s last years – the paintings here, from the collection of the Musée Marmottan Monet in Paris, are dated 1914–26 – should lead us to question. For everything about these intoxicating works seems to proclaim that the artist who inspired the label in the first place (with his Impression: Sunrise , [1872]) had somehow, without abjuring his fidelity to working sur le motif , imbibed along the way the subjective and oneiric aesthetic of Symbolism, which had ostensibly been a reaction against the fundamentally naturalistic and scientific approach of Impressionism; only Monet ever managed to square this circle. The floating, antigravitational rhythms of his compositions (noteworthy for this is the triptych Water Lilies (Agapanthus) [1915–26], here temporarily reunited); the overripe and idiosyncratic palette dominated by purples and blues; the insinuating arabesques of his brush marks; and his withdrawal from the everyday world he had once limned, in favor of a paradis artificiel of his own devising – by creating, like des Esseintes in J.-K. Huysmans’s novel À rebours (1884), an alternative reality in a house in the countryside – make him at once one of the greatest of Symbolists as well as of Impressionists. The result is certainly a triumph of pure painting, an unprecedented freedom with the matter of painting.

Claude Monet, Agapanthus, 1916–19, oil on canvas, 200 x 150 cm

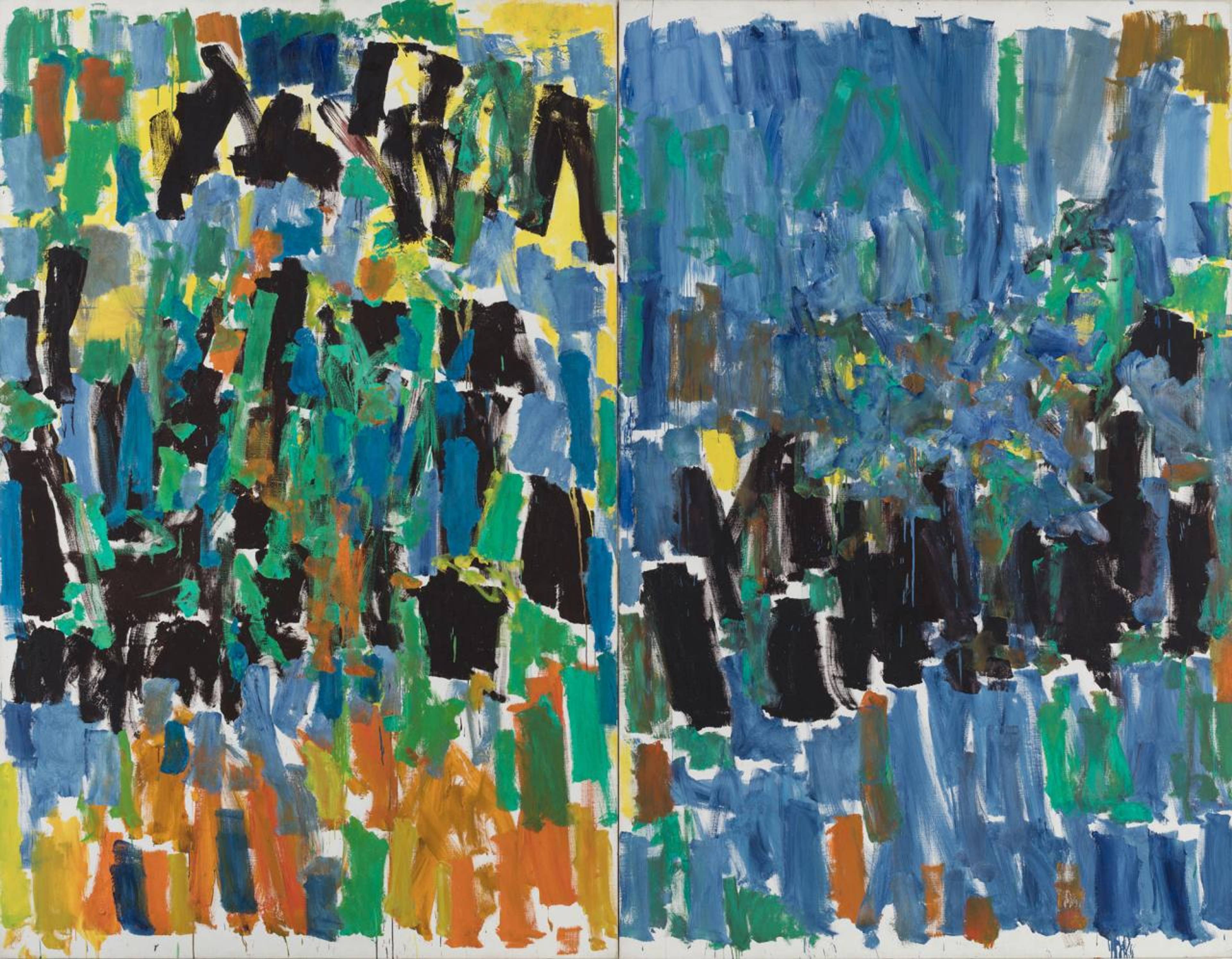

Mitchell rarely if ever tasted that freedom, though the aspiration toward it might be the subject of her work. For reasons undoubtedly both personal and cultural, her art traffics in an impatience and aggressiveness alien to Monet. No wonder Van Gogh was more her thing. Her color is brash and brilliant, her slashing brush marks utterly unlike the arabesque obliquity of Monet’s. What’s impressive in her paintings is her constant attempt to push against the edges of what she can do. She neither needs the presence of the landscape nor lets herself sink into the reverie that it inspires, as Monet did; in her paintings, the vestiges of landscape are already memory traces, on which she must try to impose some order. She struggles heroically to match the velocity of their flux. In reuniting about half of Mitchell’s twenty-one-part “Grand Vallée” cycle of 1983–84, in particular, the exhibition shows what a virtuoso she became at doing this.

Claude Monet, The Artist’s House Seen from the Rose Garden, 1922–24, oil on canvas, 89 x 92 cm

It might be churlish to complain of an exhibition that gathers together so many marvelous paintings as “Monet – Mitchell” does, but the fact is that it mainly succeeds in showing how little the two artists have in common, how little their oeuvres illuminate each other. To say, as Pagé does, that both painters were concerned with “transcribing ‘sensation’” doesn’t get us far, since the sensations themselves, as well as the modality of their transcription, are hardly comparable. But if the operation succeeds in inciting a greater appreciation of Mitchell among the French museum-going public – an assiduous one, let it be said – then perhaps the imposture is worth it, a felix culpa .

Joan Mitchell, Two Pianos, 1980, oil on canvas, diptych, 279.5 x 360.5 cm

___

“Monet – Mitchell”

Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris

5 Oct 22 – 27 Feb 23