It is somewhat ironic that the first works one encounters upon entering the lightflooded foyer of the Fondation Beyeler in Basel, site of a retrospective on Niko Pirosmani (1862–1918), is Henri Rousseau’s imposing The Hungry Lion Throws Itself on the Antelope (1905), flanked by two medium-sized Picassos. I had advised myself beforehand not to succumb to a facile reading of Pirosmani as the Rousseau of the East. Relating one artist to another is a curious reflex. Often meant as a shorthand to establish an artist’s value or describe their style, such laudations are liable to backfire – essentially reducing the artist in question to the lesser artist. The apparent goal of this exhibition in Basel is to establish Pirosmani as Pirosmani, and perhaps to make us prone to one day foolishly proclaim another artist to be the Pirosmani of the West.

Pirosmani’s Fisherman in a Red Shirt (1908) awaits us inside, standing ankle-deep in moving water, looking straight ahead, fish in one hand, pail in the other. The man’s head is enveloped in a yellow circle that resolves into a straw hat, but could just as well be a halo. It is easy to comprehend why Pirosmani’s style can be traced to Byzantine religious iconography – the figure commands our attention with a saint’s quiet self-assuredness. Overall, the painting feels shockingly modern in its reductions: A few yellow brush strokes establish some foliage; the rest is pitch-black. Working on black oilcloth, Pirosmani routinely developed dark backgrounds, bringing negative space to the front by suggesting physical forms. Here, the fisherman’s knee-length breeches are scantly indicated by some vertical lines between his shirt and his fully painted legs.

View of Niko Pirosmani, Fondation Beyeler, Basel, 2023

Still Life, n.d., oil on oilcloth, 100.5 x 136.7 cm

Nanny Goat, 1919, oil on cardboard, 83.4 x 101 cm

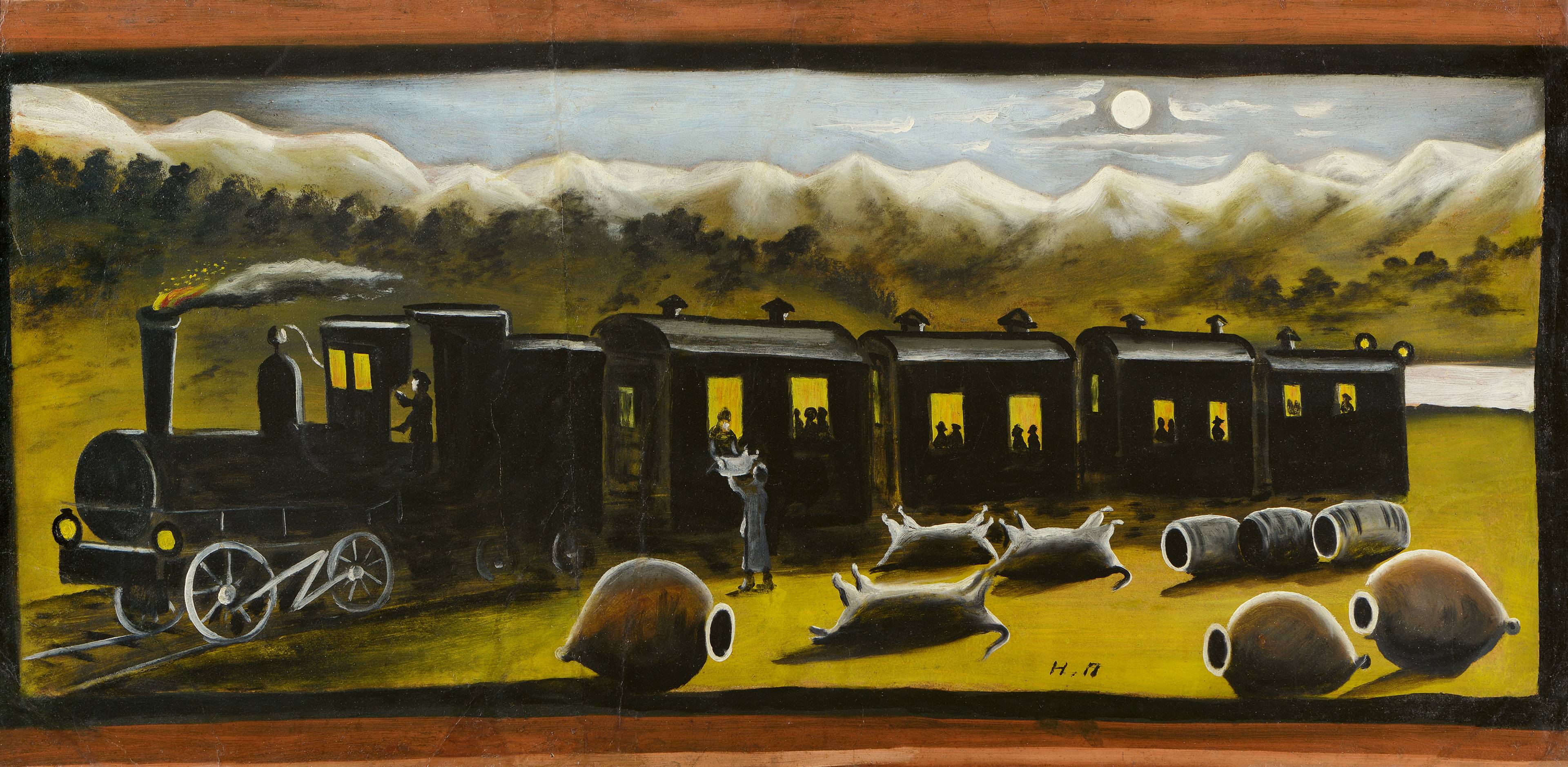

Little is known of the fisherman’s painter. Around 1900, Pirosmani, who had received no formal art education, began producing signs and paintings for dukhas (taverns) in Tbilisi, which won him the admiration of a local group of young artists. At a volatile political moment, as the Georgian patriotic movement strove for independence from the Russian Empire, his images commemorated the turn of the century in the rural Caucasus, simultaneously conjuring a way of life already lost and offering flash-like glimpses of the future ahead. Train in Kakheti (n.d.), for instance, shows a steam engine pulling four dark railroad cars in a midnight landscape, the passengers’ silhouettes visible through the cabin windows. The train has come to a halt, and an exchange of goods is taking place. In the ocher foreground, wineskins and casks are strewn about, while a full moon shines on a snow-topped mountain range behind. Despite its clear composition and balanced use of color, the painting strikingly refuses to be fully deciphered.

Perhaps most prominent among Pirosmani’s motifs were animals domestic and wild – cows, goats, lions, wild boars – which he depicted with a straightforward simplicity. (It is this hallmark in particular that earned him the comparison to a certain French contemporary who also painted so many beasts.) A giraffe painted in 1905 stands in profile against a plain background, head cocked slightly towards the viewer, filling out the entirety of the frame. Rather than aiming for a realistic representation of an animal he had probably never seen in person, the choice of colors and simple forms convey an idea of a giraffe at once wonderfully stilted and oddly ennobled.

Roe Deer and Landscape, 1913, oil on cardboard, 98.5 x 70.5 cm

Woman with a Tankard of Beer, c. 1905, oil on oilcloth, 112.6 x 90 cm

What does it mean to see the work of Pirosmani more than a century later? The show’s curator, the Kunsthalle Zürich’s Daniel Baumann, has had ties to cultural practitioners in Georgia since the early 2000s, when he initiated a series of semi-regular exhibitions in Tbilisi. Several Georgian scholars contributed to the show’s catalog, and two artists were invited to add directly to the exhibition, in a bid to answer this question. Thea Djordjadze’s (*1971) contribution, a nine-chapter hub of text posters, photos, and magazine and newspaper reproductions framed in sheet metal and silver-gray wood, invites us to see the world in which Pirosmani’s works originated. In another room, curtained floor to ceiling in white, Andro Wekua (*1977) has paired the artist’s somber Roe Deer Drinking from a Stream (n.d.) with his own Short Note (2023), an intricately hung metal sculpture of a camellia flower and a palm leaf that obstructs a clear view of the painted doe, and Face Looking (2022), a small, painted portrait that appears to gaze in the deer’s direction. The delicate tableau is a ready idiom for a capacious act of looking backward: transfixed by a singular reverence, but obliged to part the foliage of the present moment to get a clear view.

The Kakhetian Train, n.d., oil on cardboard, 70 x 141 cm

___

Niko Pirosmani

Fondation Beyeler, Basel

17 Sep 2023 – 28 Jan 2024