Things are bad. Wars rage, the planet heats, liberal democracies erode, resources dwindle, colonialism is back, if it was ever gone. At Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg, the group show “Utopia. The Right to Hope,” is seeking answers – and has found no shortage of utopias.

Just past the entrance, the exhibition presents artworks that treat with utopias of the past. Tucked away on a plinth is Russian collective Chto Delat’s 2013 wire miniature of the Monument to the Third International, an unbuilt, 400-meter-tall skyscraper designed by Vladimir Tatlin in 1919–20. Where the Ukrainian modernist’s unrealizable dream might represent a moment just before the USSR turned into a totalitarian regime, a floor-strewn field of cast-iron stars – recognizably Soviet, although not explicitly marked as such – conceived by Stephan Huber (*1952) and Raimund Kummer (*1954) in 1991 (Firmament II), dates from a moment when the notion of communist utopia had long since been exhausted. On a nearby wall hangs a 2011 photograph by Thomas Demand (*1964), of a paper model of the control room of the Fukushima nuclear power plant. Its artist, as is his wont, destroyed the mock-up after taking the picture, like the promise of safe atomic energy dashed by natural disaster.

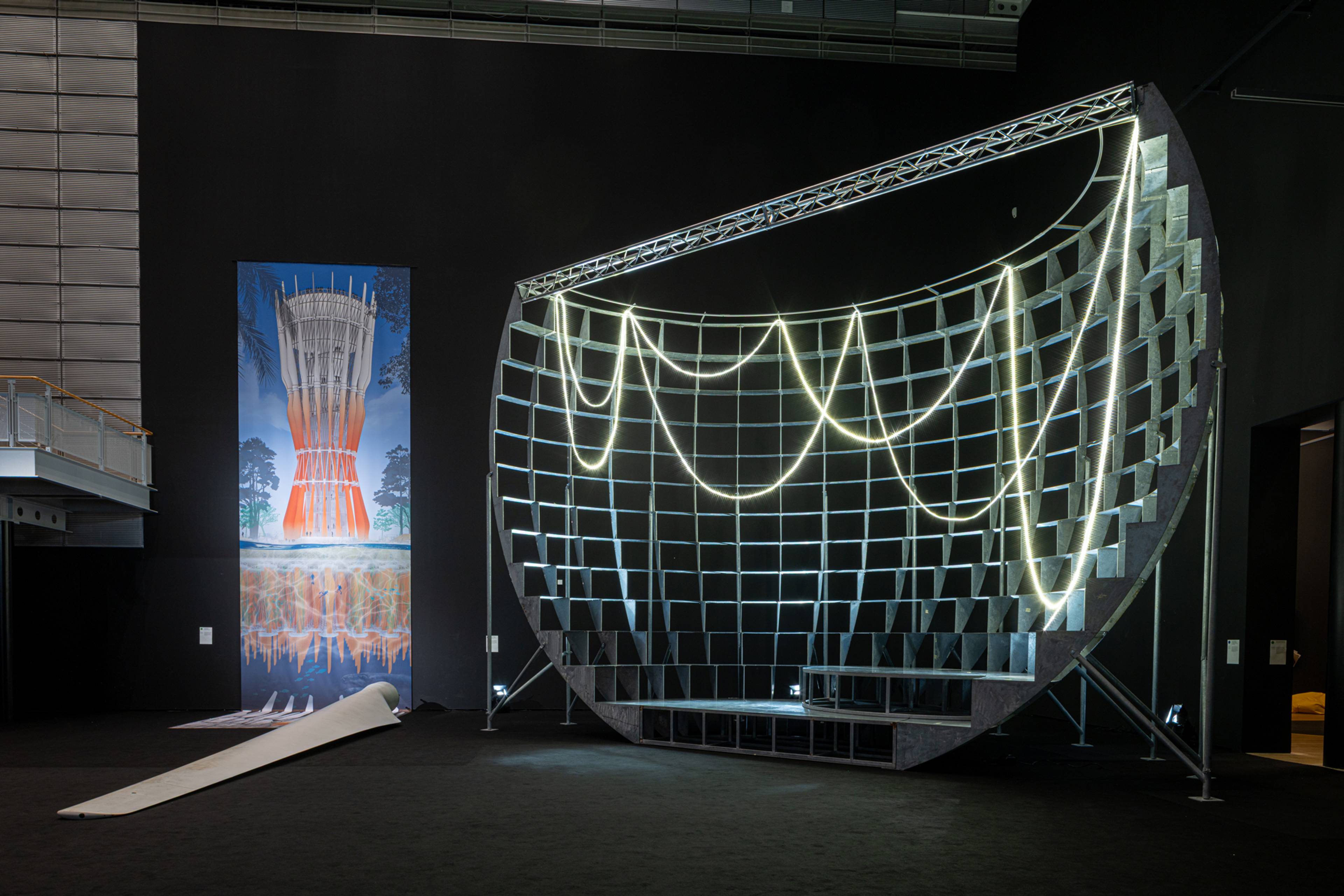

View of “Utopia. The Right to Hope,” Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg, 2025. Courtesy: Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg. Photo: Marek Kruszewski

The Kunstmuseum has made a point in the recent past of organizing exhibitions that deal with social issues, such as “Power! Light!” (2022) or “Oil: Beauty and Horror in the Petrol Age” (2021). With its religious undertones, “The Right to Hope” reminds me of a 1964 radio debate between philosophers Theodor Adorno and Ernst Bloch, who stated at their conversation’s outset the anachronism of utopia following the Holocaust and another World War. It’s a subject, in that sense, that tends to invite excess, reflected here in 110 works by fifty-nine artists and collectives – a grouping that, heavy on video, it’s hard to imagine seeing entirely on one visit (a nod, maybe, to the impossible optimism of making and seeing museum exhibitions).

Utopia, the curators claim, is a project for a society that doesn’t yet exist. But it hasn’t always been so. Utopia was once a literary genre that, born at the dawn of the modern age, and following the eponymous island in Sir Thomas More’s 1516 book, was long thought of as a travelogue to distant places. Only later, in the run-up to the French and other bourgeois revolutions, was utopia conceived as a prospect for society, as a possible future order. In that light, Phantom Island (2025), a stage-set-like installation by Philipp Fürhofer (*1982), is an apt totem for the Wolfsburg show: sheathed in soft, transparent plastic strips and emitting a faint smell of rubber, the mirrored column at its center reflects back a distorted image of anyone who comes to look.

Philipp Fürhofer, Phantom Island, 2025. Installation view, Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg, 2025

If this “Utopia” was a land mass, it would probably not be one island, but an archipelago, given a loose scenography that avoids a central narrative to address, in clusters, the likes of democracy, inequality, sustainability, and the rights of nature. Some works are adjacent to design and architecture, fields where utopia prevailed as an ethic as late as the techno-optimistic 2010s. Similarly, a number of contributions here respond to very specific problems, such as how to travel long distances carbon-free: in the large-scale video Fly with Pacha, Into the Aerocene (2023), Tomás Saraceno (*1973) proposes beautifully light, silvery balloons as alternatives to electrified transit, which depends on lithium mining that has proved devastating in indigenous Argentine communities. As Aldous Huxley and George Orwell so famously riffed on the excesses of industrialized society in Brave New World (1932) and 1984 (1949), respectively, one person’s utopia is another’s dystopia.

Technologically bettered tomorrows are not altogether absent from this exhibition: Nuotama Frances Bodomo’s (*1988) Afronauts, a 2014 video about an African space mission, is notable in clearly laying out a horizon for hope. But in 2026, many cutting-edge technologies and the dreams they enable are now in the hands of libertarians whose hearts are set not on social undertakings, but quite literally on escape: from our dying planet to Mars, or at least from liberal nation states to neo-feudalist settlements in international waters (hear the echo of More’s fantasy?). These latter-day visions, puerile in their bluntness, are for the few, yet have prevailed vastly in our culture over the likes of Inventing the Future (2015), a left-accelerationist manifesto that, written by Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams just a decade ago, now seems incredibly dated and forgotten. I am again reminded of Bloch and Adorno, who speak of the melancholia of fulfillment: once technology enables utopia, its best parts are usually left out.

View of “Utopia. The Right to Hope,” Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg, 2025

Some works turn 180 degrees away from tech-fueled visions of progress, like melanie bonajo’s (*1978) Night Soil – Nocturnal Gardening (2016) or Ursula Biemann’s (*1955) two-channel Forest Law (2014). Grappling with pressing issues like food deserts and the deforestation of the Amazon, both videos seem all too willing to risk romanticizing the other, by suggesting that reconnecting with the earth and ancestral knowledge is all that the salvation of late-industrial societies requires.

There are also works in this show that do not give up their secrets so easily, and perhaps these are the strongest. Take Cao Fei’s (*1978) Whose Utopia (2006): the twenty-minute video, which was shot in a lightbulb factory in China’s Pearl River Delta, focuses on faces, on human movements broken up into mechanical fragments, on the labor of industrial capitalism – until something odd happens. The workers start dancing, serenely, before picking up instruments and beginning to play music, the factory floor become a space of whimsy, productive no more. There is some relation to The Undercurrent (2019–), an ongoing video project by Rory Pilgrim (*1988), where young people in rural Idaho speak about the ways in which the climate crisis intersects with their lives. Like Cao’s work, the British artist’s is filled with music, and while it certainly might be accused of seeking refuge in youth, its subjects are in a process of learning, just as we are as their viewers. It allows for an openness that delivers a welcome respite from the kind of didacticism that “Utopia” invites.

View of “Utopia. The Right to Hope,” Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg, 2025

— For more on how contemporary art is looking at polycrisis without freaking out, get an e-paper of Spike #79 – The Pessimist Issue —

“Utopia. The Right to Hope”

Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg

27 Sep 2025 – 11 Jan 2026