The fluffy verbiage of the press release for this show – stressing its “unique” character – does little to prepare its readers for its grandiose actuality. A “curatorial experiment” less on the part of Wolfgang Tillmans (*1968) than of the museum itself, this presentation allowed the artist “free rein” over what is, in fact, a full-blown institutional retrospective, no less than a site-specific intervention into six thousand square meters of the Centre Pompidou’s Bibliothèque publique d’information (BPI; Public Information Library), now defunct and awaiting, like the rest of the museum, a massive, five-year renovation.

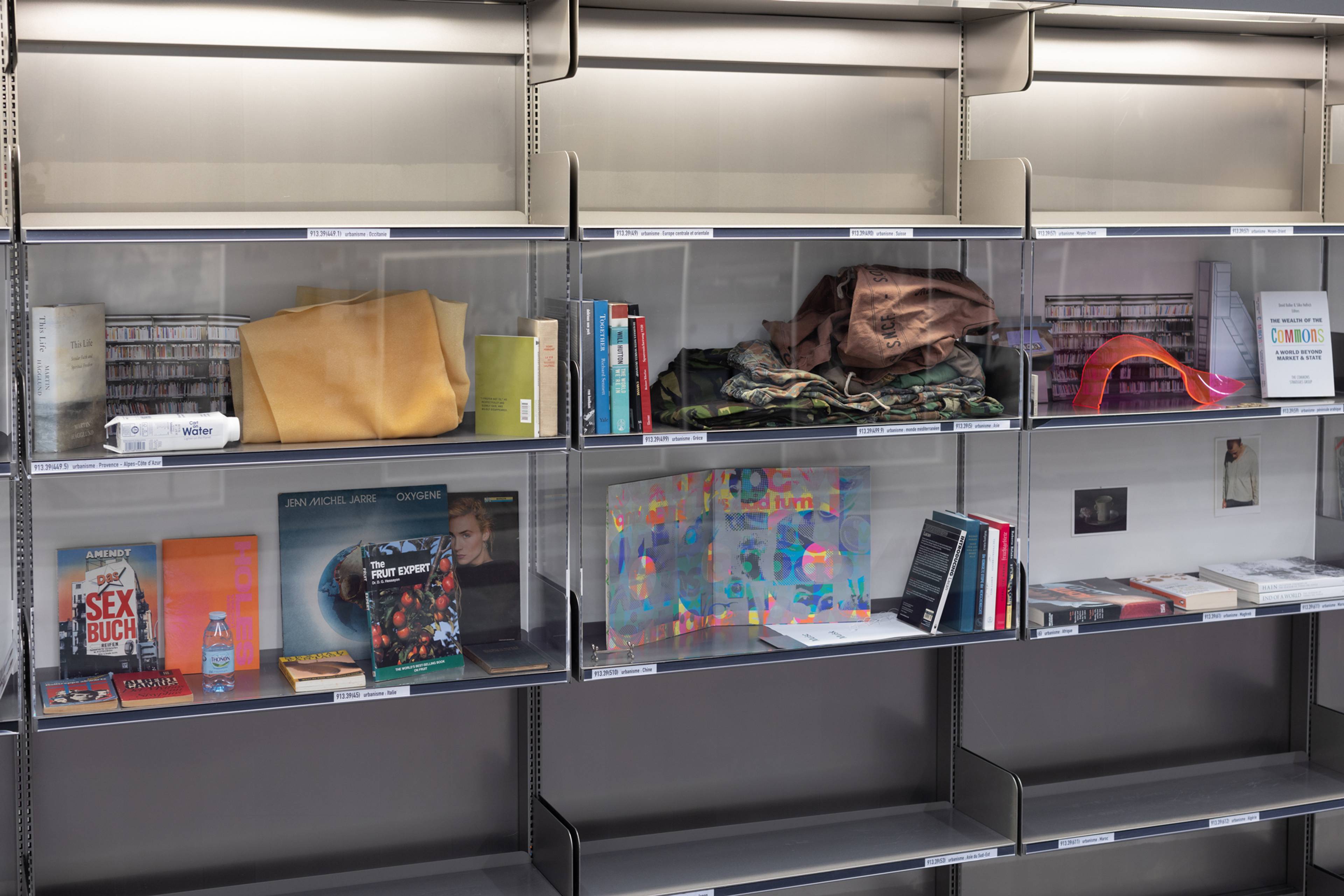

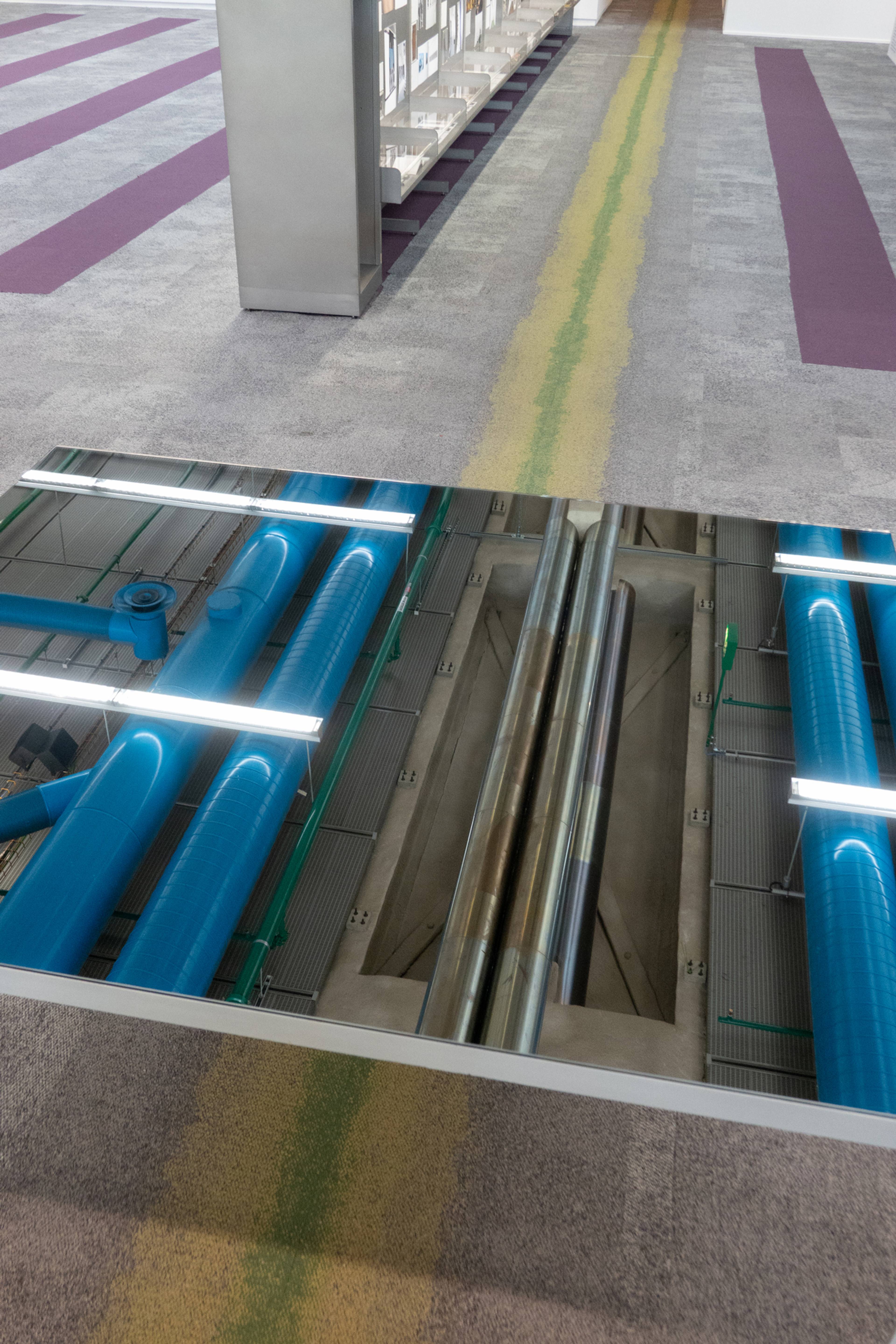

Almost entirely vacated, the library’s infrastructure has not only been exposed, but aestheticized, a site of knowledge production now become a kind of romantic ruin. Its leftovers have been woven into a complex scenography by architect Jasmin Oezcebi, whose exhibition design merges existing hardware – furniture-marked grey and purple carpets, old signage, workstations re-equipped with video monitors, benches, desks, shelves, and vitrines, these last lowered to stage the artist’s innumerable commercial works for magazines, publications, and album covers, or affixed with mirrors to reflect the building’s ceiling – with minimal architectonic interventions, such as some darkened windows, or a huge white curtain enclosing a lounge-y video area (nevertheless pulsating outwards the artist’s sound compositions).

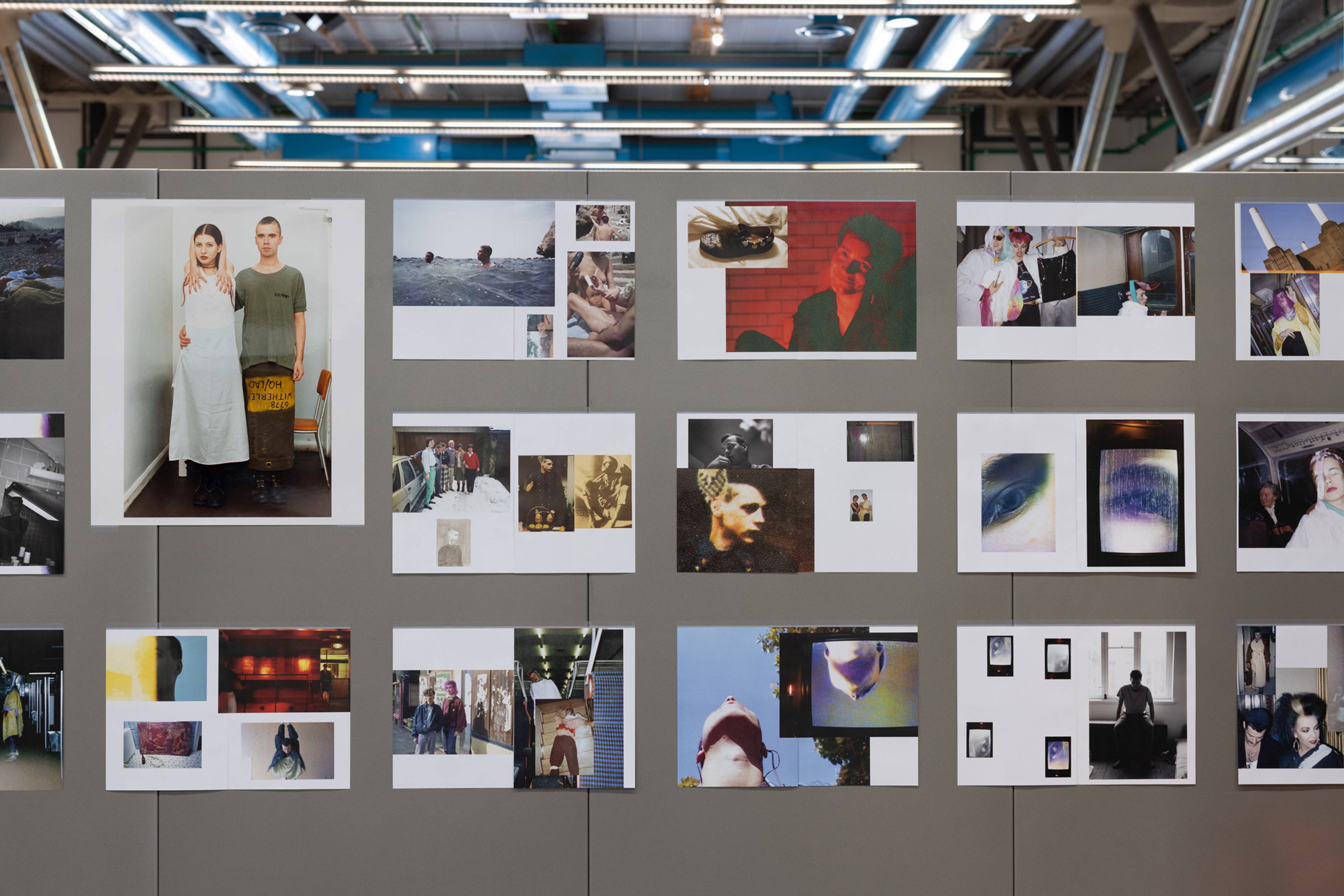

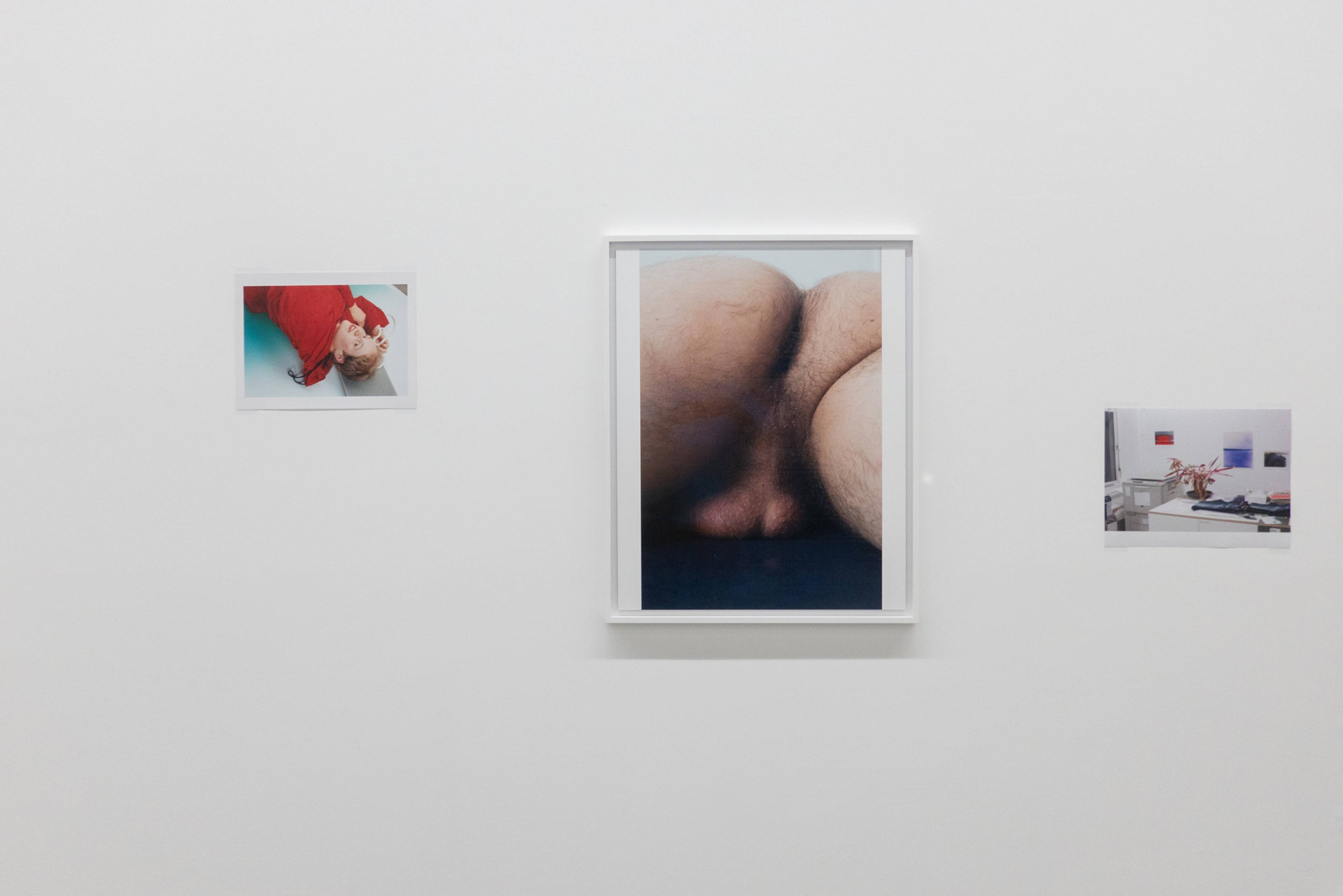

Seemingly spontaneous and ephemeral, and at times whimsical, Tillmans’s installations have, in fact, always been carefully arranged, their pictures edited as high-gloss prints or simple photocopies, usually in modest sizes. Seldom delivered in frames, they’re more often pinned or taped directly to the walls, a presentation that resonated well with the “project”-oriented aesthetics applied since the later 1980s by the likes of Group Material. Simultaneously, exhibiting with the Cologne gallerist Daniel Buchholz, the artist made, from an early age, a preceding generation of “art photographers,” and especially Düsseldorf School protagonists like Andreas Gursky, Candida Höfer, or Thomas Ruff, with their high aspirations to fuse the monumental rhetorics of history painting with a photographic editing technique that allowed ever-larger formats, look hopelessly outdated. And not only for formal reasons.

What Tillmans caught perfectly was the moment when a “new normal,” paced by techno’s 4/4 beat, ended both the 1980s and the sense of differentiating “high” art from “low.” Born out of alternative – and especially gay – lifestyles, DiY entrepreneurship, cheapening flights, and still affordable rents in a widening – even globalizing – world, his lens raised to eye-level DJs, models, musicians, and the more or less “privileged poor,” often including himself and his friends. In an easily available social medium, his images also sent strong signals out to any special-interest reader, be it of BUTT, i-D, or the German music monthly SPEX, to make this new normal available to the suburban periphery: Think of the producer Richie Hawtin/Plastikman sitting in his stuffy Windsor/Ontario home, or of the fashion designer/DJ Rachel Auburn in front of her home decks, intimately cuddled by her son – and even his casual self-portraits, decked out in Adidas. Entirely unlike the painfully exploitative focus of Nan Goldin or Juergen Teller’s staged, ready-to-go decay, this “If they can do, I can do too” message was also all-too-happily adopted into a new aesthetic of consumption, his exhibition-turned-editorials anticipating social media turning everybody into their own curator.

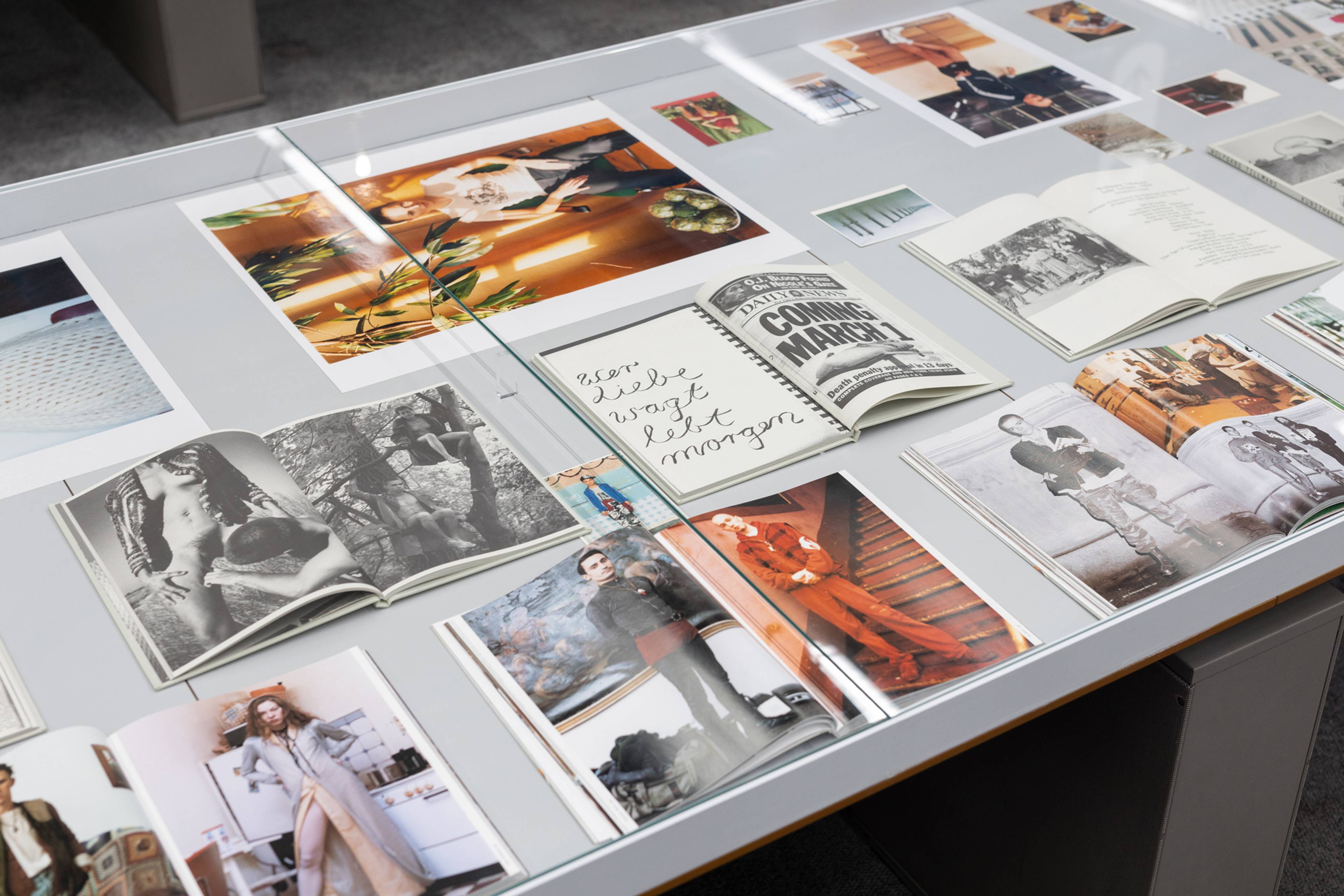

To crib from Catherine David, herself a former curator at the Pompidou, it is rewarding to untwirl the “retro-perspective” Tillmans has woven into the BPI, from early analog and recent HD photography to the research-based installations of his “truth study center” series (2005–): tables containing thematic collections of newspaper clippings, image and text documents, and ephemera touching wider political issues. One thread is especially fruitful to follow: his dedicated deconstruction of photography as medium – see his camera-less experiments with chemicals and light-sensitive paper, not to mention the simpler physics of cracking and folding – in contrast to “the photographic” as concept across visual technologies (not only analog and digital photography, but video, time-based media, scientific optics, and industrial reproductions).

His adoption of the “picture cluster exhibition” as his own relentlessly elegant, sometimes-nauseating format also historically matched a more general transformation in art and curating around 1990, one that saw a dissolution of the singular work of art into the twofold modalities of the “exhibitionary” and the “discursive.” Not that any artwork since has literally come in the shape of an exhibition or a text; the turn is more of a structural one. Yet, today’s post-post-conceptual “practices,” based especially on artistic research and/or institutional critique, still understand the exhibition as a prime site of artistic production: The more meager or “in the making” a show looks, the more it should be taken for granted as art – never mind that Tillmans has made every single nook, joist, and cabinet here into a presentational device.

Still, the best one can say of “Nothing could have prepared us …” is that, rather than overwhelm the viewer, the artist is inexhaustibly patient in garnering their attention towards the site of the exhibition, the modalities of display, the things shown. This being said, size matters – as does the presentational mode, with its many redundancies. But there is always the image, too. You need to go close in order to catch the details, as with a small but spectacular seascape backgrounded by a surreal cone of light. Here, it is the title that unveils a drama: “Italian Coastal Guard Flying Rescue Mission off Lampedusa” (2008). But you may also simply enjoy yourself looking through the artist’s eyes, amplified by the human sensibility-blowing capacities of HD photography, catching either some baroque-ish still life with fruit or a showering Frank Ocean (“Frank, in the shower,” 2015).

___

Wolfgang Tillmans

“Nothing could have prepared us – Everything could have prepared us”

Centre Pompidou

13 Jun – 22 Sep 2025