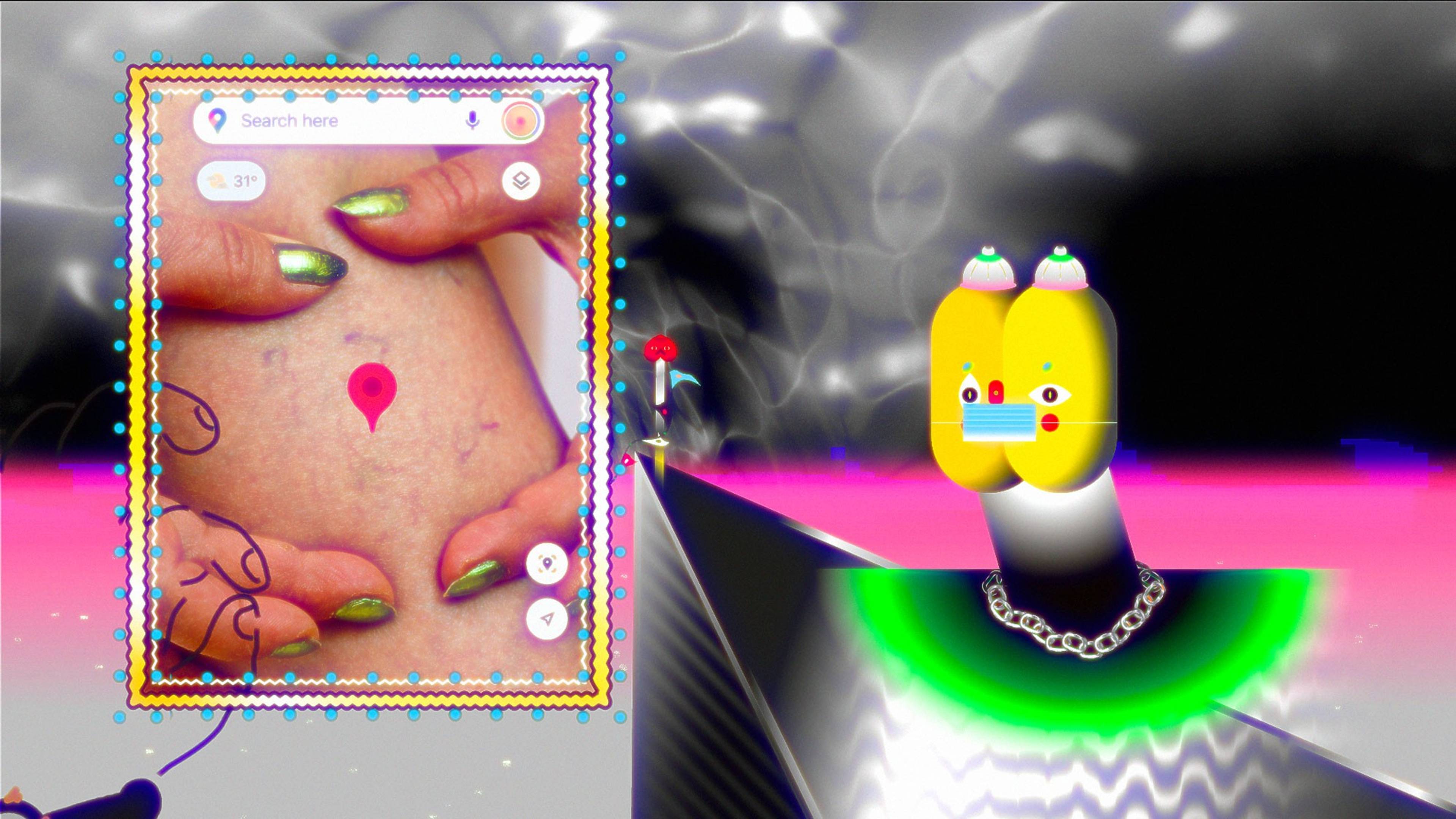

“When I think I’m at the center of the areola, I’m just at the edge of the nipple,” proclaims a yellow-headed figure wearing a surgical mask in the middle of an indigo-blue sea. This punchline concludes both their own quest for satisfaction and the viewer’s attempt to grasp the storyline of Sorry for the late reply (2021). The animated film’s protagonist, an artist by the name of Wong Ping, is obsessed with the visual similarity between lighting and varicose veins and ends up trapped in the body of a saleswoman after ecstatically sucking at her varices. He quickly writes an email to a curator: “Sorry for the late reply. I’m trapped inside someone’s calf … :( Let’s talk about the exhibition when I’m out.” The journey to escape the corporal confinements is punctuated by several dream-like episodes, including a third-tier marching band and a chameleon suffering from racist abuse, until Wong finds himself, eventually, at the edge of the nipple.

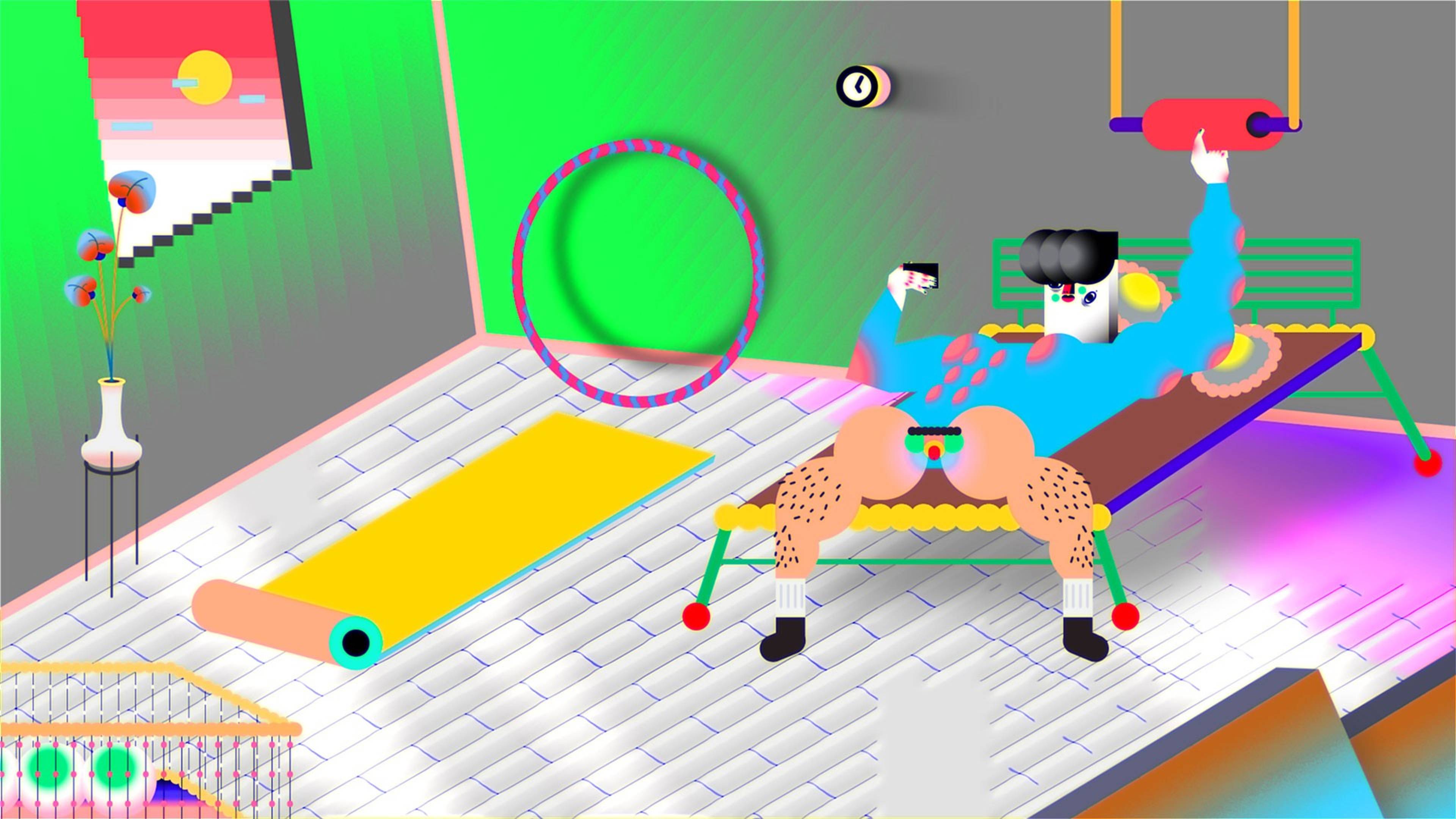

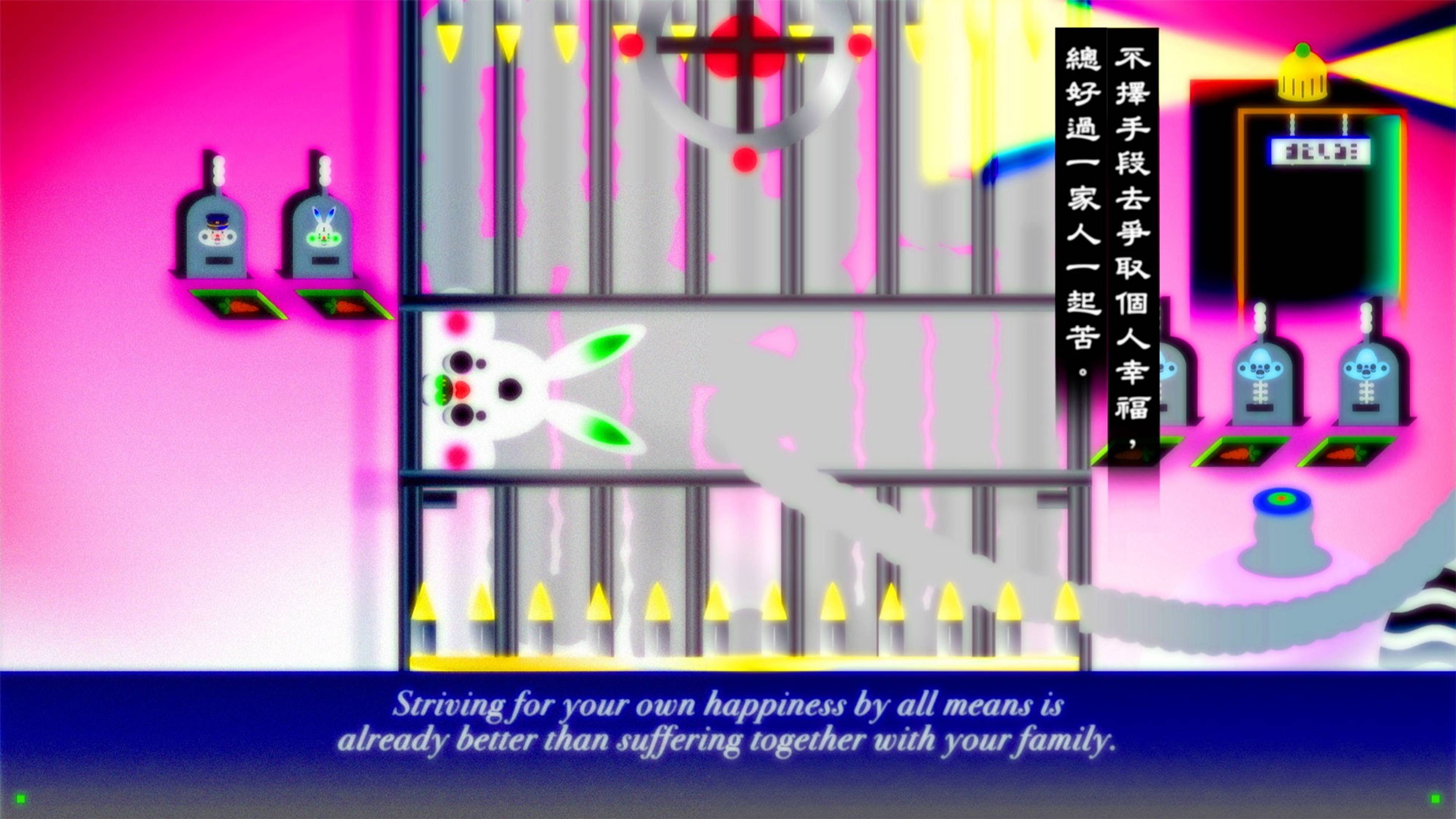

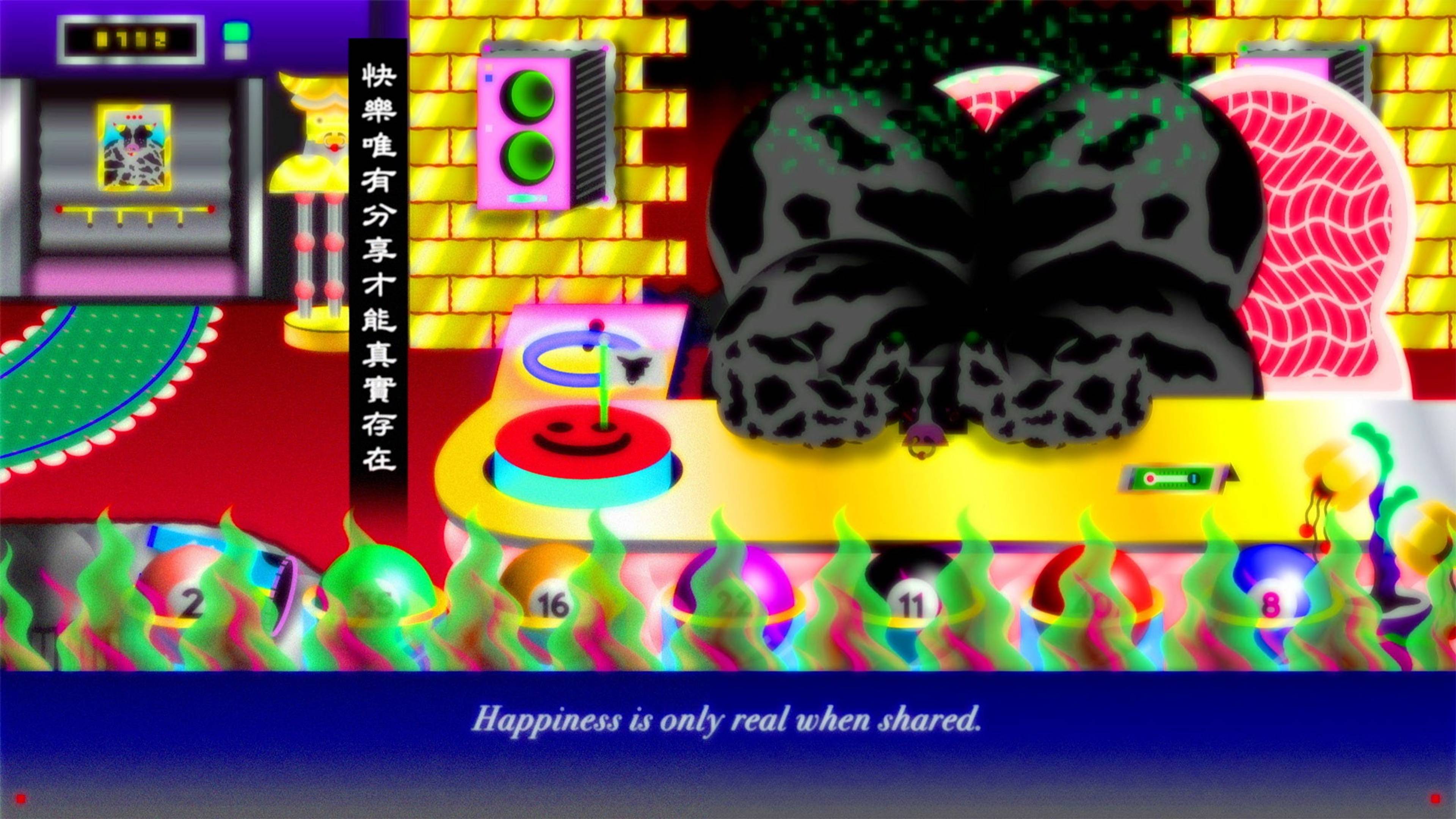

Stills from Sorry for the late reply, 2021, single-channel animation, 15 min.

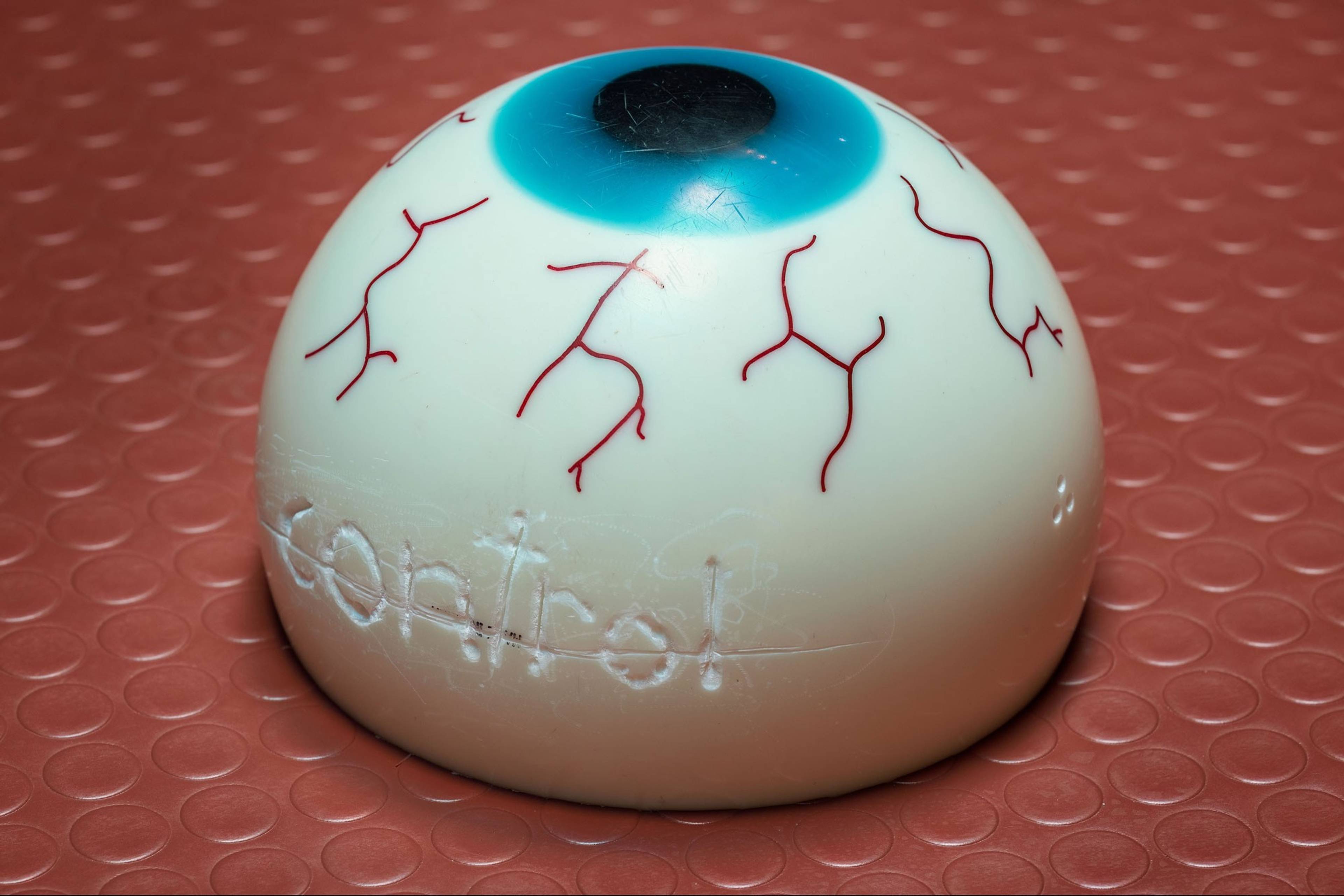

The most recent of the four video works in “edging,” Wong’s solo exhibition at the recently inaugurated MAK Contemporary, Sorry for the late reply reflects the artist’s experience of the pandemic and his profession. Wong, born in 1984 in Hong Kong, was favored with a quick-start career in the art world in 2019. Before submitting his work to a local film festival, making animations was an online hobby. While the rudimentary imagery – geometrical forms, schematic colors, and movements – might be rooted in self-teaching, his retention of this distinct aesthetic, reminiscent of the early internet and 1990s video games, is deliberate. Childish illustrations, like money symbolized by golden coins, and humorous details distract from the marred nature of the characters: cuboidal heads missing eyes or mouths; single extremities with inflamed neon joints; and so on. Isolated, they wander through flat, monochromatic backgrounds or remain confined to cramped interiors where the story unfolds from a few personal attributes: a weight-training bench for an individual with a petite penis, say, or a fishing pole for an artist seeking inspiration. Combined with fast-paced, absurdist narratives, the animations keep their viewers on edge, their attention consumed by following subtitles (in Cantonese and English) and digesting the visual overflow. Only when all four screens light up in different colors, during the pauses between films, does one become aware of the backdrop. In the middle of a darkened room, viewers sit on a three-tiered platform coated with orange-studded flooring. On the top of the pyramid, a bloodshot eye the size of a bowling ball stares at the ceiling, its surface carved into with the words “ruin me” and “control,” the latter crossed out, forming a circular phrase.

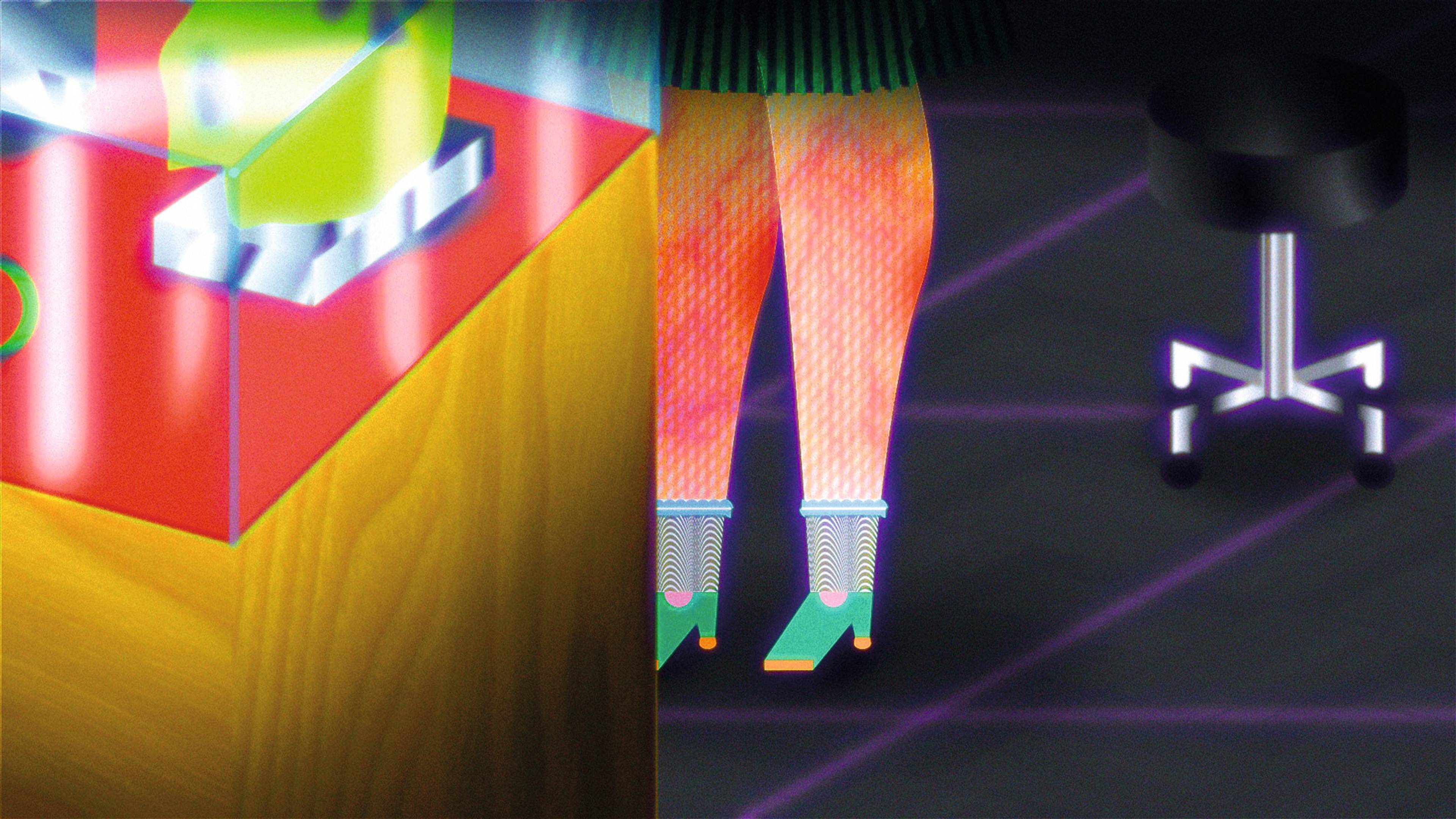

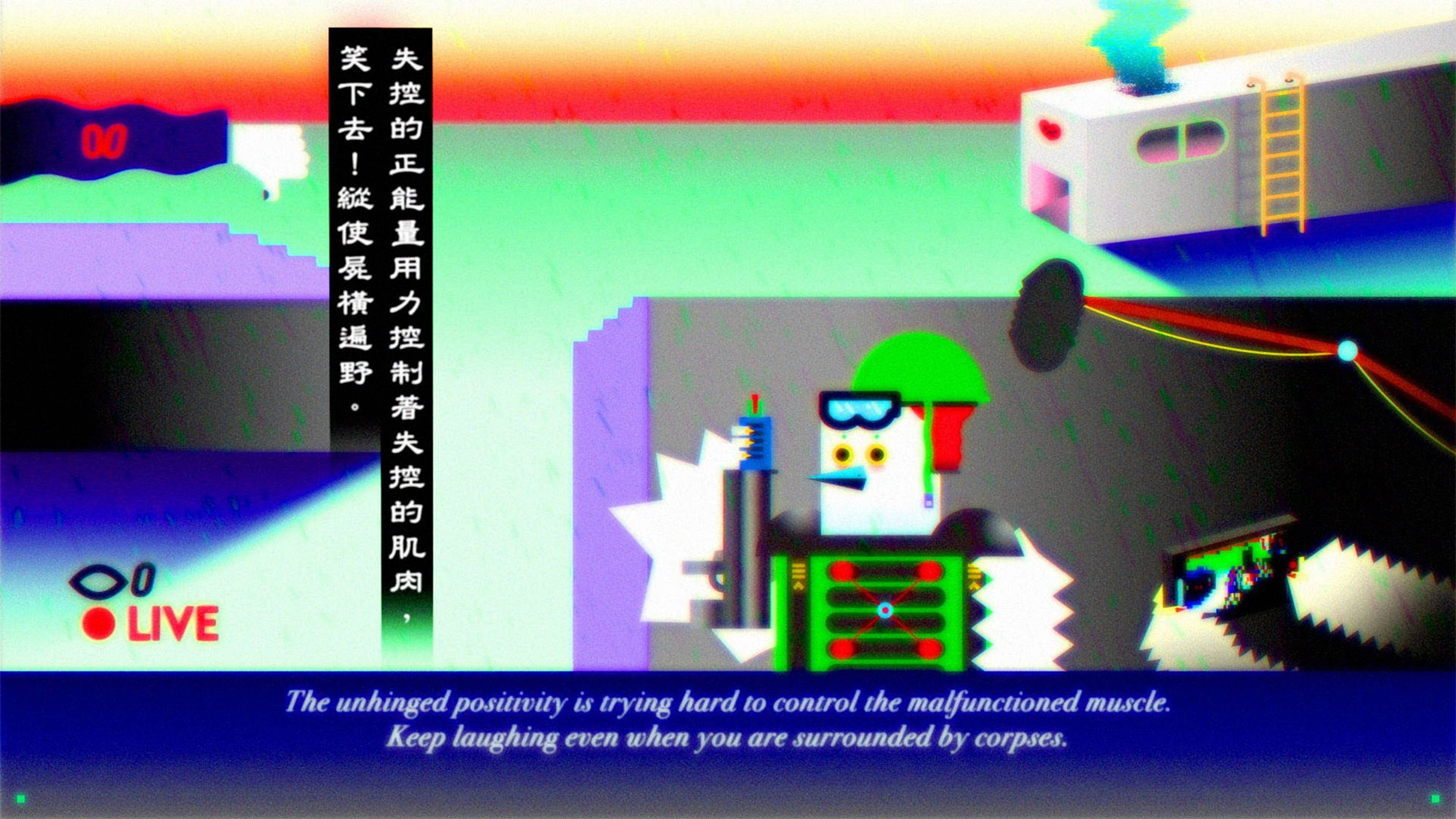

In Fables 1 (2018) and Fables 2 (2019), a feminine computer voice recounts animal tales that begin with “once upon a time” and conclude with a moral statement. The faith of three conjoined triplets trying to pursue their individual dreams, for example, is summarized: “Striving for your own happiness by all means is already better than suffering together with your family.” More optimistic is a romance between a turtle and a pregnant elephant turned nun who is discriminated against because of her monolid: “Talent would never go unrecognized, only could people be born in a wrong time. Your time will come when vulgarity and bad taste become trends.” Each story unspools in a single frame, with dreams, thoughts, and flashbacks depicted in browser windows or selection fields. The videos originate in the artist’s observations of life in the streets of Hong Kong just before the popular protests of 2019–20. While the scenarios take on metaphorical meanings in that context – as with an imprisoned activist or a two-headed judge, for example – the abstract animal figures offer sites of identification with their moral dilemmas beyond Hong Kong.

Still from Wong Ping’s Fables 1, 2018, single-channel animation, 13 min.

Stills from Wong Ping’s Fables 2, 2019, single-channel animation, 13 min.

Humor and sex pierce through the multi-layered narratives of Wong’s animations, causing high-speed chaos. Pleasure, both onscreen and in the seat of the giggling spectator, is not an aperture to psychoanalytic self-discovery, but a short-lived moment of joy that suspends morals, shame, and control. In Who’s the Daddy (2017), the protagonist doesn’t question his desire for submission, not even when he realizes that it’s connected to a lullaby his mother sang to him as a child, but dreamily hums the same song for his baby. The work’s title, like the exhibition’s, prefigures the sexual subtext characteristic of Wong’s work. Edging – the sexual practice of stimulation until the point just before orgasm – serves as a metaphor for human desire stunted by convention and online desensualization. Yet, this shouldn’t be misunderstood as cultural pessimism or an invocation of suppressed drives. Wong Ping doesn’t mourn the phantasm of a long-lost authenticity, but evokes pleasure as a force of individual and political liberation. Still, the release of tension, through sexual satisfaction or narrative puns, is only momentary, before the next screen lights up and lulls us back in.

View of “edging,” MAK, Vienna, 2023. Photo: kunst-dokumentation.com/MAK

___

“edging”

MAK

25 Oct 2023 – 31 Mar 2024