Every time I start to write about the situation in Ukraine, I receive a message that my hometown, where my parents and my thirteen-year-old brother live, is getting bombed. It is a very small village in the Donetsk region in eastern Ukraine, which has remained in the non-occupied zone during the eight long years of this war. One of the horribly impressive elements of this invasion – beyond the repeated and violent attacks like those on the town of three square kilometres that I call home – is the scale of informational weaponry. It constitutes a hybrid tool, influencing both digital and physical fronts, more powerful than we have ever seen before.

Ukrainian civilians are constantly receiving false news about evacuation routes, captured sites, and injured people. These reports are hindering our abilities to move ourselves and our relatives to safer places, not to mention our ability to stay sane. We have long questioned the authenticity of digital media, especially in times of war, when videos and photos posted online are widely misinterpreted, photoshopped, or even filmed on-demand with a team of hired actors (as was the case with recent videos purporting to show captive Ukrainian soldiers, both in the occupied part of the Donetsk region and on Zmiinyi Island). Now, we are witnessing the perpetual activity of the Russian state propaganda machine, which has long been preparing its own citizens to become an unofficial army of civilians – recruiting those over whom it rules, or is planning to rule, to continue spreading this misinformation on their own.

Propaganda methods which were already used to lure people into the trap of the so-called Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics – misleadingly designated as “independent” states as they came under Russian control in 2014 – are being repeated today in other Ukrainian territories. Fake Russian news is actively circulating on the Internet claiming, for example, that Russian soldiers are supplying humanitarian aid to people in Kherson, a city in the south of Ukraine. Eventually, news like this is meant to be used to further Putinism – a term proposed by Ukrainian writer Olexii Kuchanskyi to mean “that strange kind of huge non-human war technology predicated on the merger of legal neopatriarchy, racist violence, neoliberalist capitalism, political isolationism, disinformation and the latest surveillance equipment” – and advance its disingenuous policy of “rescuing” Ukraine from the supposed “Nazi regime” of local government.

By means of media manipulation, our opponents are building a collective memory: they show us what is important and how it happened.

In Regarding the Pain of Others , Susan Sontag points out that, “with time, many staged photographs turn back into historical evidence, albeit of an impure kind – like most historical evidence.” By means of media manipulation, our opponents are building a collective memory: they show us what is important and how it happened. Putinists, skilfully attuned to Sontag’s observations, have been pushing their agenda by constructing a story throughout eight years of war in Donbas – but their aims at narrative control started long before. For centuries, Russian propagandists have been building a collective memory of their “rescue operation” to justify their own domination over their neighbour – during the Russian Empire, during the Soviet Union, and today, against Ukrainian independence.

Beyond the fight to control the grand historical narrative, disinformation is behind many smaller-scale tragedies. The official channels used by the Ukrainian parliament are not able to counter the Russian info-weapons in real time, because these weapons strike at the most important thing – our individual sense of security. To protect us from the possible offline danger, the parliament has no choice but to disburse the online anti-propaganda tasks to all our nation’s armchair warriors, inviting individuals to try and debunk potential lies before eventually informing us of their falsity. Those manufacturing the propaganda capitalise on this uncertainty to play on our mental state, so that even people staying in safer places will pointlessly but anxiously spend time solving their riddles.

In one such instance, on 3 March, Ukrainians who were following parliament’s official Telegram channel were notified that Russian digital militaries had tagged the Google Map of Kyiv, in dozens of locations, with “Edemus” – a name for funeral services. (The tags have now been deleted.) A quick Google search reveals that these marked spots included most of the hospitals in Kyiv, as well as sites like the Muslim mosque on my street, and the buildings of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy, the university where I studied, among countless others. The credibility of the story was dubious: these locations would be easy to find, even without the “Edemus” tag on Google Maps, if occupiers really wanted to target them with artillery shelling, missiles, or airstrikes. Nevertheless, if you find one of these tags near your own house, you hardly stop to consider the time you will lose by deleting it.

The information disproving this potential disinformation might also be false now – even fake can be faked. After receiving a wave of messages about explosive tripwires set up in Ukrainian cities, the chats were full of discussion: was this report false, created to sow panic? Subsequently, it turned out that the messages were true, and that claiming them to be false was, in turn, disseminating danger.

Vlada Ralko, Together (2022)

Fake reports about victories and capitulations, safety and danger, and gains and losses are equally prevalent. All of them could be, and are, used against us. Russian propaganda is even disseminating false approvals about the creation of “green corridors” – supposedly safe passages – allowing Russian forces to target evacuation trains or other civilian transportation, as has already happened in Volnovakha, Mariupol, Chernihiv, and other cities.

On the other hand, Russian crimes have been falsely implanted by the Russians themselves, so that Ukrainians will pick them up and condemn these atrocities in our Instagram stories. This pure provocation is exactly what the enemy expects – manipulating our rage against them. On 3 March, Ostap Ukrainets, a Ukrainian author and translator, discussed these incidents in a Facebook post about Russia’s tools of information war. According to Ukrainets, the dehumanisation of Russia’s own army, in the eyes of the Ukrainian people, is one of the Russian propaganda machine’s objectives . Dehumanising its own army also implies the dehumanisation of Ukrainians to the rest of the world, as they’re painted as brutal for responding to these provocations.

The full range of our emotions is under attack in this information war. Even our compassion in response to the enemy’s lies is twisted around to reinforce the same “rescue” narrative that they construct while we are reacting to them. The Russian soldiers are not only trained in physical assault, but also in moral manipulation. From the very first day of the invasion, online and offline word-of-mouth sources were full of stories about soldiers swearing they didn’t know they were going to war. They claimed to be fooled, believing that they were continuing their ordinary training, but on Ukrainian fields and with Zelenskyy’s permission. What answer can we offer to their sobbing oaths of ignorance, except helping these soldiers with our own scarce resources, which would be better used to fight against them?

Now the creation of fakes is so far out of control that we are in a situation where protagonists and antagonists become allies, as they, in a constant state of stress and panic, begin to retransmit and produce fakes of their own. We misinform our neighbours about possible alarms; we begin to consider every passer-by suspicious.

Again, it seems that Russia has been preparing for this hybrid explosion for too long. They not only knew how to attack our government, our armed forces, and our civilian population on all fronts; they also knew how to strategically provoke a multidimensional crisis with wider geopolitical affects. Putinists created a scenario of widespread emergency, where the expected lack of humanitarian and military aid is compounded by a refugee crisis and informational confusion. In the past, we have marked the scale of a war by the number of participating countries – but what is the designation for a deliberately-planned invasion indirectly carried out on outer territories, with cascading effects both physically and virtually?

Not only we are negating the facts, facts are negating the veracity of other facts.

Another message on my phone:

Part of my mother’s family was killed in a suburb of Kyiv: my aunt with two small sons, nine and four years old. My grandma sent me a letter by my nine-year-old cousin, written in the days before he was killed:

“There is a war in Ukraine. War is very dangerous. Putin is a bad man. He starts a war for no reason, he lies to his own people. I am very scared now, but I believe in the victory of my country. Ukraine is a strong state, supported by many countries. But Russia, though a large country, does not have an army. Now I am sitting in the basement, writing this text for you. I am worried about my family, because in our city of Bucha there are fights every day. We are a shield for our capital city Kyiv. If I were 18, I would go to fight for my Ukraine, but I am only 9 years old now, so I am at home with my family. I reassure my mother when she is in despair and entertain my younger brother. I believe we will win. I am proud that I am UKRAINIAN!!!”

I had to stop working on this text for a day.

But I returned to it the next day, because it seems to be my only weapon. And this weapon – information – in other hands, forging age-old historical narratives and authentic news, has been used against us, our families, and our country for a long time. I try to stick to neutral language while writing, but what language should I use when little kids are getting killed?

Ironically, on the day I travelled to Lviv – 20 February, four days before the full-scale invasion started – I was reading an essay by Bruno Latour, “ Why Has Critique Run out of Steam? ” . In the introduction, the philosopher talks about military experts constantly revising their strategic doctrines, not unlike art critics feverishly trying to keep the old tactics up-to-date. According to Latour, the mistake we made was in believing “that there was no efficient way to criticise matters of fact except by moving away from them and directing one’s attention toward the conditions that made them possible.” The denial of facts in this war goes far beyond deconstruction or socio-cultural critique. As a result of the amount, frequency, and intensity of the information we’re bombarded with, collective denial feels to be ubiquitous. Not only we are negating the facts, facts are negating the veracity of other facts.

What help can we, as a community engaged with arts and culture, offer on this front of war, made of synthetic truths? Instead of a constant process of conditioning facts, Latour proposes a probing multidisciplinary inquiry, aimed at figuring out “ how many participants are gathered in a thing to make it exist and to maintain its existence”. However, in the mode of provoked danger, we can often find ourselves forced to abandon the plural landscape and return to the binary perception of the world. Propaganda legitimates – even justifies – thinking in binary oppositions, yet those who are invaded are forced into this binary ex post facto by their invaders’ design. Although it deals in plurality, propaganda always reduces to a double-ended narration. It consists of only two possible participants: victim and perpetrator, invader and invaded, living and dead.

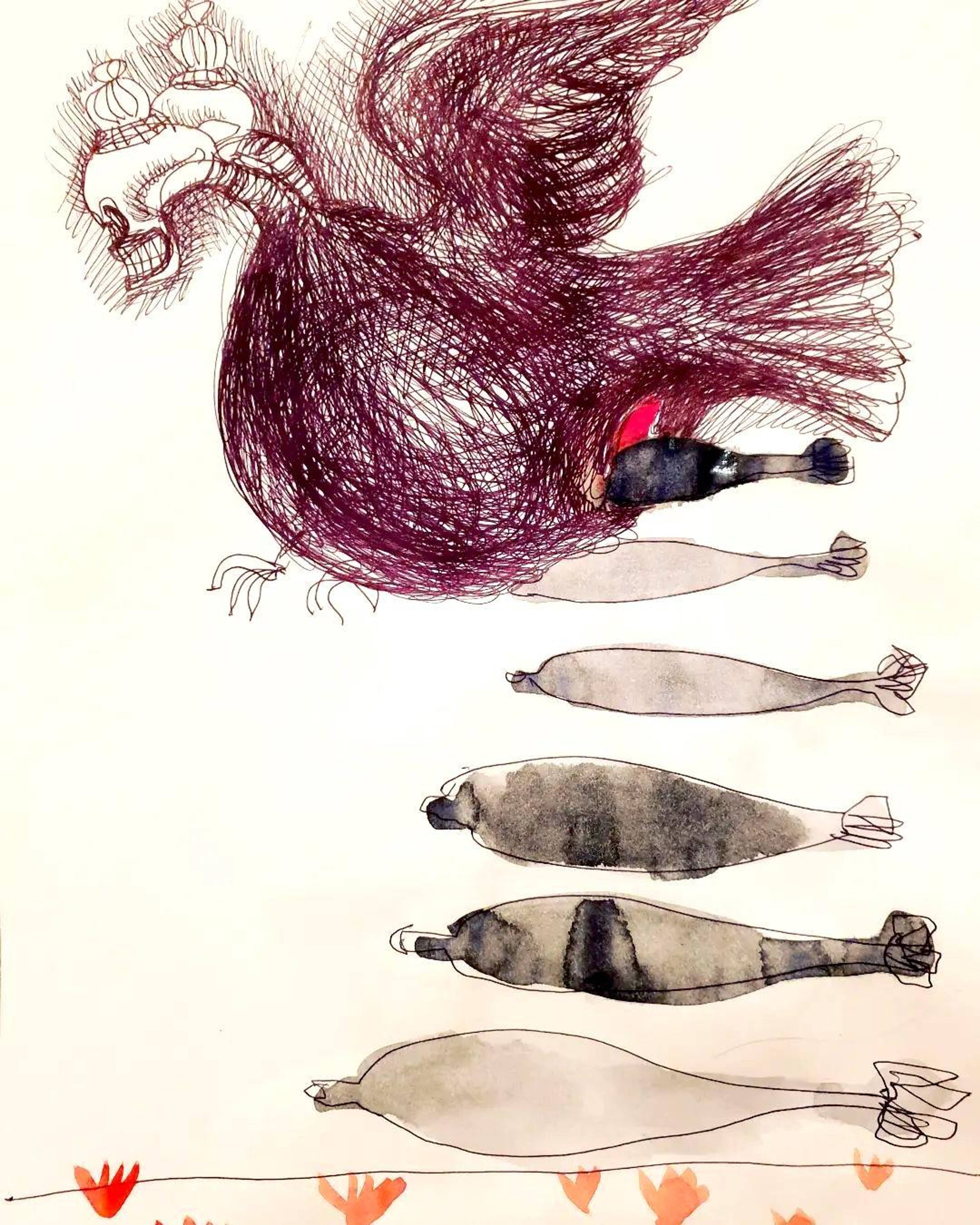

Vlada Ralko, The Dove of Peace Feeds the War (2022)

MILENA KHOMCHENKO is an independent art researcher and writer, and the coordinator of the platform Dreams For Sisterhood based in Kyiv, Ukraine.

Thanks to CLEMENS POOLE for additional editorial support