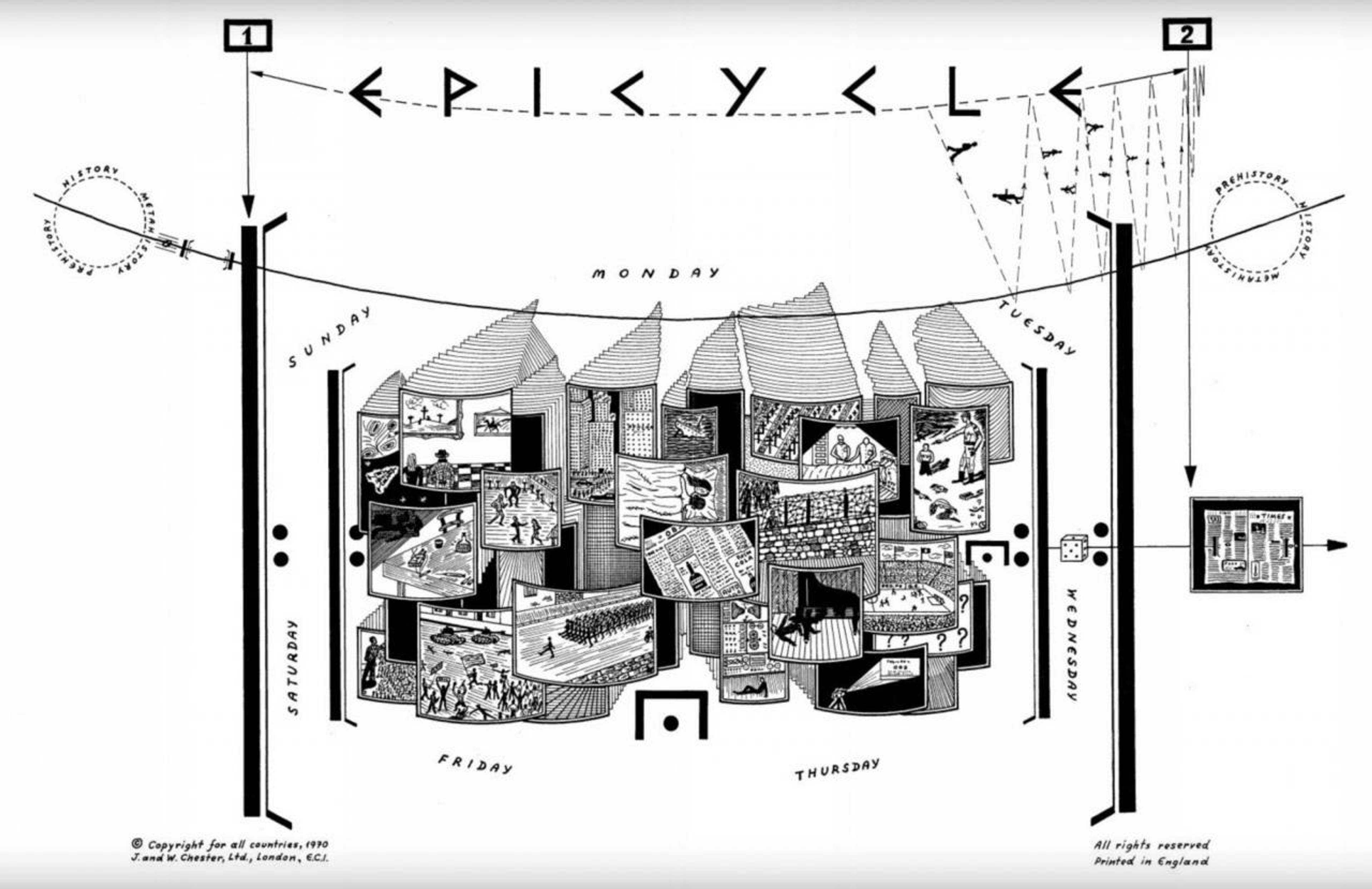

In spring of 2017, I went to the opening of documenta in Athens. On the first morning, in the Megaron Concert Hall, the curtain rose on the press conference to reveal all of the curators and some of the artists sitting onstage performing avant-garde Greek composer Jani Christou’s score Epicycle (1968–present). They were making a lot of noise up there, howling and stamping their feet. And we, the audience, we were told, were also part of this performance. The performance was to continue in the conservatoire and each of the exhibition’s venues from 11:00 AM to 9:00 PM each day, and later that year throughout Kassel; but really it’s been going on all this time, everywhere, since Christou composed it in 1968, and we’ve all been performing in it. From the day I was born, I was part of the Epicycle. We are all part of this dead experimental Greek composer’s performance and there was no way out. So that’s when I realized all of life is a performance.

This August I visited the Sistine Chapel, where photography is forbidden, although they can’t really stop you. My neighbourhood of SoHo, New York, is an Instagram set. Every sunny day it’s full of young women and their sidekicks choreographing and shooting scenes from their imaginary lives on popular crosswalks, or in the fake flowers that bloom outside certain restaurants. More people come to take photos in front of the Louis Vuitton shop and the artist collaborations in its windows, the big cartoon Urs Fischer cats and so on, than to buy anything from there. The same trends are present in art: Tate Modern’s show of Yayoi Kusama, “Infinity Mirror Rooms”, is sold out until April. There are currently five competing phantasmagoric Van Gogh experiences touring the States, its deserted spaces, orbiting one another like moons in the starry night. Back in SoHo, a simulacrum of the Sistine Chapel has just opened down the block. One of the holiest places in the world, for Catholics and art-lovers alike, is remade as a space for self-worship, in which one can take pictures with the angels. But that’s not what angels are for.

Life has become a performance, a rather banal and meaningless one. That may have been the case for centuries, but even more so now. The only thing we can make now is ourselves; day after day, again and again. To sculpt one’s own individuality has ballooned into an endless task. To post every day, to express yourself creatively, to have opinions on the churning discourse.

Some dude brought a copy of Camille Paglia’s Sexual Personae: Art and Decadence from Nefertiti to Emily Dickinson (1990) to my gym and read it between sets. I went to a party in Midtown in summer thrown by the Ions, a pair of anonymous podcasters who wear masks and disguise their voices, and spoke to a young lady on the balcony who said she’d dropped out of art school to become a “persona”. That makes a lot of sense for the present, and she’s doing very well. But how did we end up here?

Detail from Piero della Francesca, Madonna della Misericordia (The Polyptych of the Misericordia), 1462

Here’s one story. In the ’60s and the ’70s, in America, artists and pop stars began to tell us that we all had something to express, and we were all going to be stars (following, perhaps, English occultist Aleister Crowley’s visionary sacred text The Book of the Law [1909], which affirms, “There is no law beyond do what thou wilt; Every man and woman is a star.”) Ever since, we’ve had to believe in self-expression, because we’ve wanted to believe that we are unique. Self-expression is a proof of uniqueness, and even free will. At the same time, in the ’60s, Andy Warhol and his Factory were also elevating glamour and personality into an art form. Writing about the Factory – and in particular the catalogue for Warhol’s 1968 (the same year as Epicycle was composed) retrospective at Moderna Museet, Stockholm, which was mostly just photographs of the artist and his entourage out on the town – Swiss curator and critic Martin Jaeggi noted, “The superstar is a star for his own sake, just as the Hollywood star no longer acts parts, but above all plays him or herself. The star no longer helps to sell a product of the entertainment industry, for now the star is the actual work, their persona is the work of art.”

In the ’80s, children like me were told we were delicate beautiful snowflakes, miracles, were each of us one of a kind. We were individuals, and would express that individuality through our creativity and our consumption of branded goods. In the ’90s, the MTV years, alternative culture was in the ascendancy. Identities were defined by the consumption of cultural objects, by subcultural alignments and personal style. In the 2000s, with reality TV triumphant, and Paris Hilton and Kim Kardashian’s sex tapes in the mainstream, stars were becoming famous for being famous. At the same time came the rise of the “creative” and the “hipster”. Everyone was alternative in exactly the same way, and it felt like subculture had died and was never coming back. User-generated “content”, we were told, was the future; and in the 2010s, we all became content producers, and finally we could all become stars, famous for fifteen minutes, artists in our own way. But everything we made was just about ourselves.

It’s a terminally Millennial habit to turn oneself into a brand; a habit that will surely feel quite dated, desperate, and shameless quite soon.

In the ’10s, Kim Kardashian became the most famous celebrity in the world by making her image and personality into a spectacle on a scale nobody else had ever attempted. “Last year, when I wrote about Kim and Kanye”, critic Jerry Saltz wrote in 2015, “I said I was ‘struck dumb’ by the ‘collective cultural fracturing’ that they actually seemed to be engineering, and doing it with the blatant biraciality of their combined meme, and with grandiosity, sincerity, kitsch, irony, theatre, and ideas of spectacle, privacy, fact, and fiction. All that had compressed into some new essence, an essence that they seemed to be shaping as surely and strangely as Andy Warhol once formed his.” A year before, in 2014, at a dinner held in her honour at Art Basel Miami Beach, she had joked that her ass was a work of art, and everyone had agreed. She had become the apotheosis of the performance of the self as an art form, but it had all begun in the ’60s, in Manhattan, with Warhol’s Factory and his Superstars; or perhaps in Cairo, with Crowley’s sacred visions.

Jani Christou, Epicycle score, 1968

If ’80s and ’90s culture was driven by materialism, by people just wanting so much money and lifestyle, it’s now driven by narcissism. We live in an attention economy, and the self is the key unit of exchange. We no longer affirm our identities through brands and consumer objects, but rather turn ourselves into brands and consumer objects. We no longer assert our individuality through the culture we like, or even make; rather self-presentation has overrun and usurped the culture. When somebody says, “My life is a movie”, or “Last night was a movie”, it doesn’t only mean they feel like they’re in a movie; but that our lives, our scripted, filmed, edited and broadcast lives, are the dominant cultural form now, the one that’s replaced movies.

Today’s most vital cultural forms are your identity, personality, and image. And in this new cultural paradigm, the artist’s performance of themself is often more important than the art they make. The persona is the message.

My father, a Boomer, lives in the English countryside and paints for a hobby. He makes so many paintings he’s run out of walls on which to hang them. He loves painting. I don’t understand what he’s doing. He doesn’t understand why I stopped painting in high school. But, like many of my generation, I think I derive less pleasure and meaning from expressing myself than from being seen to express myself. I’m always wanting to share ideas and experiences, even though I feel disgusted by the urge. It’s a terminally Millennial habit to constantly post one’s life and thoughts and turn oneself into a brand; a habit that will surely feel quite dated, desperate, and shameless quite soon. How will we look back on these decades, these lives? How we live is embarrassing, but will like all things change. It’s already happening.

Balenciaga’s Demna Gvasalia, who was born in 1981, among the first cohort of Millennials (alongside Paris Hilton, Ivanka Trump and Jared Kushner, Beyoncé, and the Columbine shooters, Dylan Klebold and Eric Harris), often designs by deconstructing, exaggerating and mutating found tropes. His Fall ’17 Vetements show was based on archetypes like rich lady in furs, demure Parisienne, German tourist, office worker, goth. His Spring ’20 Balenciaga show did the same with desperate Euro politicians and glum bureaucrats. For Fall ’21, he took this idea of avatars further and replaced the show with a video game.

For many seasons, Balenciaga’s Instagram was a roll of photos solicited from alternative influencers, from pale, sickly artists and dour, misshapen scene kids, eager to make themselves into advertisements for around $500 a post; but on July 1st this year, the brand deleted everything, unmade itself, and turned to a blank page. By late July, Kanye West, under Gvasalia’s creative direction, was wandering the stands of Atlanta’s football stadium in a series of masks. And last month, September, Gvasalia accompanied the rapper’s estranged wife, Kim, to the Met Ball in matching all-black outfits and body stockings that obscured their faces completely. Demna and Kim, this century’s most influential and effective forces of branding and self-branding respectively, are now involved in the destruction of identity. Kim and Kanye are divorcing one another, but also themselves. And Demna’s black-hooded, faceless penitent getup from the masked ball also closed Balenciaga’s Spring ’22 show, and was the first picture posted on its wiped-clean Instagram.

Michelangelo, The Banishment from the Garden of Eden, 1508–12, Sistine Chapel

I was born in the ’80s. Michael Jackson’s Thriller was the bestselling album in the world. He embodied the American Dream: that you can be whatever you want. In his novel Platform (2001), Houellebecq’s character and stand-in Michel suggests that as a species we instinctively tend towards a multiracial, cross-cultural identity. “The only person, however, to have pushed the process to its logical conclusion”, he says, “is Michael Jackson, who is neither black nor white anymore, neither young nor old, and, in a sense, neither man nor woman. Nobody can really imagine his private life. Having grasped the categories of everyday humanity, he has done his utmost to go beyond them. This is why he can be considered a star, possibly the greatest – and, in fact, the first … Michael Jackson was the first to have tried to go a little further.” Now Kanye has gone a step further and tried to erase his identity completely, to vanish.

My old roommate used to say that Kanye seemed very frustrated, and he could relate to that feeling of frustration: that desperation to bring into this Earthly realm something as bright, as beautiful as what you are imagining, but not being able to, but not being taken seriously. It’s very relatable.

When Kanye walked around the stadium this summer in a mask, it did feel like something important was taking place: that he was relinquishing a part of his identity. How could we even know that it was him behind the mask? He was effacing himself in the stadium. He was living there, in the ruins of his identity, in the stadium, trying to make great art. Trying, and failing, to make a record as bright as what he was dreaming of, or, perhaps, to make himself into the timeless work of art that might redeem his life. Eight years ago he was saying he was a god. Now he’s nobody, rising into the light.

The most ambitious pop stars don’t just change their identity but attempt to in some way move beyond it.

For some years he seems to have been trying to create a space in which the spiritual might occur. Kanye has been on his evangelical Sunday Service journey, but also riding something of an anarcho-primitivist, Leave Society wave: building mysterious domes that open to the sun. Planning a great circular open-air amphitheatre, plus a 100,000-person choir to perform in it. Speaking in tongues, without words, to his friends. Moving to a Wyoming ranch over which wild antelope, mule deer and elk roam, at the back of which there are caves scrawled with old pictographs by indigenous American tribespeople. Where they appear in prehistoric cave art, human and humanoid figures are often drawn without distinguishing features, or shown with animal heads. There was a facelessness at the beginning of art, and again here at its end.

The drawn-out spectacle of Donda (2021), with its foggy listening parties and masked wanderings, cannot quite obscure the absence of a hit record. But it’s hard to express yourself while also destroying yourself. With his aimless and ongoing performance, with his disyllabic “Donda chant”, Kanye is moving closer to Jani Christou, and his own grand Epicycle . His entire career has been a work of art. “KANYE”, suggests the also faceless, hidden writer Angelicism01 , commenting on the first performance in the stadium, “MIGHT HAVE STAYED QUIET LIKE A DOT IN THE SNOW WHEN THE WHOLE WORLD CAME KNOCKING. … Kanye had no need to make a single sound in the snow.”

Pop represents change. Pop can transfix us, can spellbind us. The most ambitious pop stars don’t just change their identity but attempt to in some way move beyond it. Houellebecq’s Michel, from Platform , right after his thoughts on Michael Jackson as the first star, as having transcended the boundaries of the human, goes on to wonder, “Did this mean that the first cyborg, the first individual to accept having elements of artificial, extra human intelligence implanted into his brain, would immediately become a star? Probably, yes.”

Around the corner, by the fake Sistine Chapel, the walls are plastered with Adidas posters featuring a one-legged model and the copy, “World’s first bionic model”. Grimes has also embraced her cyborg side lately, issuing pronouncements on how global warming is good, how enforced farming is really not a vibe, how radical decentralised UBI might be achieved through cryptocurrency and gaming. This fall, in this uncanny moment, our most unorthodox pop stars, Grimes and Kanye West, offer two paths for the stalled culture: to embrace posthumanity, or destroy your identity.

___

Persona (Part 2) can be read here.