The Unidentified Oumuamua interstellar object has just left the Solar System. The last sign that we may not be alone has departed. This is a very young universe, very near to the beginning of its story, and we are alone in our corner of it and probably its entirety. We may be living through what feels like the stupidest moment in history but, at the same time, our minds are also the sui generis apogee of consciousness and imagination that has ever existed anywhere in the cosmos. One of the qualities that makes us unique among all other beings is our ability to appreciate beauty. Another is our ability to dream of places and worlds we have never experienced. I have been writing this column for six years now and this is the last one I’ll write.

One has to try and be different. And right now, when so many have succumbed to doom and foreboding and self-pity and self-loathing, shouldn’t we try and be more optimistic? It’s a new decade and a moment of great possibility —

I wrote these lines in February 2020. As it turned out, the new decade didn’t begin so well and but a month later there were morgues outside on the streets and I was wandering around my tiny East Village studio succumbing to foreboding, thinking I might die, or that my parents were going to die before I ever had a chance to say goodbye to them. I still think we should be more optimistic though, I still believe this is a moment of great possibility, now even more strongly.

Life is still beautiful, it’s culture that’s in the doldrums

I long for the world outside, the sinking world that’s drowning under its own representations, and for a chance to return to the real, and the wonder of the city, and the beauty of nature, and people you can reach out and touch. The lives we were promised feel so distant now. And when this is over, I hope we can throw more caution to the wind, and be more adventurous (or whatever else one finds important), and find different ways of living, and go out and take a hold of the world in all its glory before it’s too late. I want to feel more of life. Tomorrow I’ll go to the grocery store, which reminds me of a line from Ella Plevin, who used to have a column here alongside me, who used to write tweets, and once described how, “Sometimes your heart just splits open in a Dutch supermarket and you’re crying with gratitude for every breath you’ll ever take”—

I wrote this in April 2020. I thought we were going to remake the world but we didn’t. I thought we’d give everything for our lives to come back, for a chance to try again, but now the pandemic is done and that hasn’t led to a great explosion of joy or a sense of renewal of purpose. We are as unhappy and worried as ever. We just find other things to feel doomed about, another reason why you have to despair blooms every hour of the day, a million reasons floating in the air, from one person to another, alighting in the palm of your hand. Although I read this early this morning:

“I had a French professor who once said if you just did something like going to the supermarket and experienced it fully without the goggles of habit and catégories you would go crazy with pure sense and joy.”

The Oxford Dictionaries word of the year is “goblin mode,” meaning to live self-indulgently and reject social norms and expectations, and to never apologize for it. That sounds great to me. Around 2016 there was a Great Weirding. The grand narratives began to collapse, our faith in authorities and experts collapsed, a big feeling of doom engulfed us, we began to write and speak about society in a very doomed way, to use doomed words. Our grasp on what’s real continues to crumble. These were the Oxford Dictionaries words of the year during the Weirding:

2015: Face with Tears of Joy emoji

2016: post-truth

2017: youthquake

2018: toxic

2019: climate emergency

2020: no word this year, as “it quickly became apparent that 2020 is not a year that could neatly be accommodated in one single ‘word of the year.’”

2021: vax

2022: goblin mode

We went quickly from tears of laughter and joy to pure absolute despair, the undoing of truth, of goodness and kindness, of the climate, the total dissolution of language itself, of the ability of words to express how we live now, fears for our health, for our bodies, which were all we had left, for our willingness to remain part of society, before arriving here in goblin town, and the rejection of what has come before. It’s a new day in the Anglosphere. One has to try and be different after all.

Pantone 18-1750 Viva Magenta

Pantone’s Color of the Year for 2023, Viva Magenta 18-1750, is “expressive of a new signal of strength … brave and fearless, and a pulsating color whose exuberance promotes a joyous and optimistic celebration, writing a new narrative,” a new way forward that’s grounded in the past. “Rooted in the primordial,” says Pantone Color Institute Executive Director Leatrice Eiseman, “Viva Magenta reconnects us to original matter. Invoking the forces of nature, Pantone 18-1750 Viva Magenta galvanizes our spirit, helping us to build our inner strength.” The mood is changing I say. Everywhere you look there are signs. There are signs everywhere.

Artforum has just been bought by Penske Media Corporation (PMC), a massive publishing conglomerate that also owns Art in America, ARTnews, Variety, Rolling Stone, Women’s Wear Daily and more, which means the most powerful and influential art magazine is now just a part of somebody else’s plans for making money, and that there are no more top-quality independent art magazines in the States.

PMC is buying up all the American art press. This latest acquisition was reported by ARTnews, which is part of the same group, so the story can be read as approved messaging from the new owners. “The magazine,” they write, “has published numerous groundbreaking pieces, including artist Nan Goldin’s 2018 essay on her opioid addiction, which prompted the formation of P.A.I.N., her activist campaign targeting the Sackler family for their involvement in the marketing of Oxycontin … In 2019 Artforum published an essay by Hannah Black, Ciarán Finlayson, and Tobi Haslett about the involvement of Warren Kanders, then co-chair of the Whitney Museum board of directors, in the biennial and his fortune’s ties to the production of riot gear and tear gas. The essay has been considered critical to Kanders’s eventual resignation and the Whitney’s decision to cut financial ties with him.” These were very important essays – and activism in the art world, and particularly here in New York, was the main story of art in the 2010s, the most significant series of events – but it’s funny to see them cited like this in what is effectively a press release about how great Jay Penske is and how committed PMC is to the publication’s future, how wonderful it will be for the “community,” as though he bought the magazine in which every gallery wants to advertise and be reviewed because of its reforming zeal, because he wanted to take on big pharma and arms dealers and make the world a better place. No stories about ART were mentioned in the ARTnews story about Artforum of course. A few days later it was announced that the magazine’s excellent literary criticism quarterly Bookforum would be shut down immediately.

Since 2017, when it had its last scandal, Artforum has built up a position of considerable moral authority. Of course you can’t sell out to PMC and kill your sister publication without losing some of that; but it seems to me that the magazine is giving up some of its moral authority right at the moment when cultivating an air of rectitude is becoming less important in culture again, right as the ground is shifting once more beneath our feet.

Gudetama: An Eggcellent Adventure began streaming on Netflix in September 2022

As Artforum is embracing capitalism and corporate consolidation, the Guardian is turning to nihilism. In her column from last weekend, “I am getting into neo-nihilism – it is so soothing to conclude that nothing matters,” Emma Beddington celebrates the relief of accepting the futility of everything (other of her columns from this year include: “I’ve taken 263 photos since arriving in Venice, my husband has taken five – it would be nice to have a few more of me”; “A fox has taken my hens – weeks later I am still finding feathers and my heart is leaden with grief”; “It’s cheap, it’s quick, it’s a pit of culinary depravity – save me from the microwave”; “I shout at plants and browbeat the vacuum cleaner. I tell the dishwasher I hate it. What’s wrong with me?”). On Sunday she noted “a cultural vibe shift” towards nihilism, suggesting that “traditional sources of meaning – fulfilling work, forming a family, having a home, planning a future – have never felt more out of reach for so many. That’s terribly sad when you think about it: no wonder it feels more soothing to conclude that nothing matters.”

“‘Why don’t you just give up and let the moss reclaim you?’ … I’ve whispered countless times since,” Emma continues, “imagining inhabiting a silent, primeval forest, nostrils filled with the damp, earthy smell of moss as it slowly conquers my inert form.” She is moved by a desire to go die in ancient woodland, like a Japanese teenager in the Aokigahara Sea of Trees suicide forest, and inspired also by Gudetama, a depressed anthropomorphic cartoon egg yolk from the same country. “Gudetama can’t see the point of anything in the face of their certain fate: being eaten,” she says. “They are ‘joyless and hopeless and completely without opinions or ambitions, except to be left alone to squelch and loll in their own malaise.’” They are Nietzsche’s Last Man in the form of a broken cartoon egg with a Netflix deal. They are Pepe the Frog for Guardian readers (Emma is moved also by the blunt-headed burrowing frog Glyphoglossus molossus, “by contemplating its impassive features and imagining myself belly-down in a Thai marsh”). There is also an egg at the exact geometric center of the central interior panel of Hieronymus Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights (1490–1500) in the Prado, but it doesn’t represent joylessness, hopelessness or nihilism, by my interpretation, but rather fertility and sensuality, nature’s bounty, the birth of a new world in a moment of immense historical change.

Detail from the central panel of Hieronymus Bosch's The Garden of Earthly Delights, ca. 1490–1500

In the lead essay from the new n+1, “Why Is Everything So Ugly?” the editors express their shared disdain for the ugliness of contemporary architecture and design and the 21st-century American cityscape. It’s refreshing to see a plea for beauty, a call, one might even say, for a return to architectural tradition here, because I also think that all this corporate aesthetic mediocrity, combined with academic disdain for questions of beauty, is bad for the soul; I believe a more beautiful, or imaginative, environment will improve the lives of those who live there and pass through. In recent times the desire for beauty has often been framed as a reactionary impulse, but it seems the boundaries of the discourse are shifting and opening up again.

“It’s logical, I suppose,” Beddington writes in her Guardian nihilism op-ed, “that roiling permacrisis makes us more receptive to the notion that striving is pointless.” This is an amusing take from a newspaper that until not long ago had a daily countdown of how many days we had left to save the world (we ran out of days, and the countdown faded into the past like everything else). It’s also a tacit admission that this popular insistence that society is doomed, we’re all doomed, we’re lost in permacrisis, in omnishambles, we’re deep in the end days and there’s nothing any of us can do to stop it, is profoundly nihilistic, and far more harmful than the performative adolescent nihilism of internet trolls and ironists over which so much scare was mongered and panic sown in the late 2010s.

What if this is all a terrible downward-spiraling illusion we’ve conjured around ourselves together?

The combination of both articles, one calling for an end to all the ugliness and the other acknowledging that believing you’re doomed leads to nihilism, also suggests, I would hope, the unravelling of one of the most frustrating strange paradoxes of media today: we’re told every morning that life is miserable and hideous, which it’s not, and also that culture is high-quality and life-affirming, which is plainly ridiculous. This is breathtakingly diabolical because the opposite is true: life is still beautiful, it’s culture that’s in the doldrums. Although I suggested this once and a stranger replied, “It’s not a strange paradox at all. You tell people their life is lousy, then you can sell them something that will fix them.”

The world kept threatening to fall apart but never did, but we convinced ourselves that it’s irrevocably broken, which is just as bad, perhaps worse. What if it’s all a terrible illusion? What if all this discourse about how terrible everything is, these essays and shows about how awful our lives are, how hard it is to be a person in the 21st-century first world, only contributes to the illusion that our world is so broken, so without hope or rays of light? What if this is all a terrible downward-spiraling illusion we’ve conjured around ourselves together? An illusion that is formed by the culture that describes it. An illusion we’ve forgotten we made and now mistake for reality.

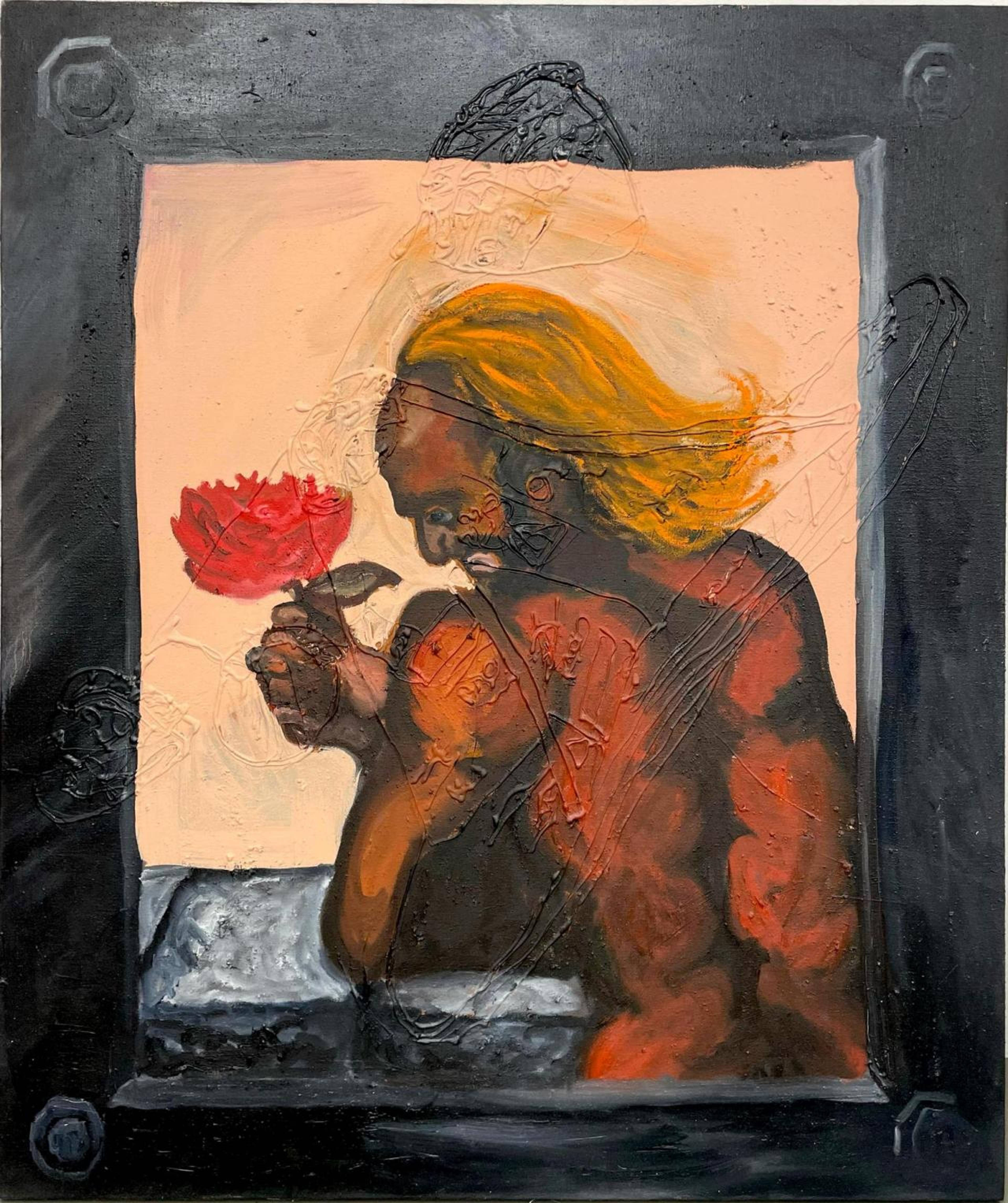

Mathieu Malouf, The Psychologist (Virgil), 2022, exhibited in "SCULPTURE", at Jenny's, New York, December 7, 2022 – January 21, 2023

Fashion is entering a new era. For the six years I’ve been writing this column, its most influential figures have been Alessandro Michele at Gucci, where he was appointed creative director in Fall Winter 2015, Demna Gvasalia at Vetements and then Balenciaga, from Fall/Winter 2016, Kanye West at Yeezy and then Adidas, from 2016, and Virgil Abloh at Off-White and then Louis Vuitton, from Spring/Summer 2019. They have transformed how we think about fashion, self-expression and identity. Now Michele has been fired and Demna has declared his allegiance to the Canaanite fertility demon Baal. Now Virgil has died, now Kanye has gone mad.

Now the Satanic Panic has been resurrected. Last month a Balenciaga campaign sparked a massive controversy after children were photographed alongside bags in the form of teddy bears in bondage gear, leading to outraged conspiracy theorists and bedroom semioticians claiming Balenciaga was signaling its approval of child abuse and Devil worship, but here’s the thing: it wasn’t. And look: aren’t all forms of advertising inherently satanic? Nevertheless the furore became so great that the brand withdrew the campaign and issued an apology, for nothing, in trademark all-caps sans-serif font: “AT BALENCIAGA, WE STAND TOGETHER FOR CHILDREN SAFETY AND DO NOT TOLERATE ANY KIND OF VIOLENCE AND HATRED MESSAGE.”

Balenciaga's Spring/Summer 2023 bags

In another of the house’s new season campaigns, which has also been axed, Isabelle Huppert poses in a Manhattan office building somewhere in Midtown, on the desk of which in the background can be made out Michaël Borremans’s 2014 Hatje Cantz monograph As sweet as it gets , and this has also set the conspiratorial imagination alight , with the Daily Mail reporting that: “[Borremans’s] 2017/2018 [painting] series, Fire from the Sun , shows a group of toddlers, some of them with blood staining their skin, in sinister composition.”

David Zwirner’s press release for Fire from the Sun suggests instead that these paintings “portray psychological states that are not intended to be decoded,” but we have been living for years now in the floating world of signs and symbols and everything has turned to code, everything’s an encrypted chthonic communiqué waiting to be disassembled. Culture has become this unfurling infinite metatext we all write and decipher and misrepresent together. Devil-hunters used to believe rock’n’roll records contained hidden Satanic messages that would only be revealed when you played them backwards, now they look for those same messages in the curated selections of coffee-table monographs by high fashion set designers. But here’s the thing: Nobody reads those catalogues. (I’ve written for them, trust me … )

The campaign photos were also called out for the presence of a Matthew Barney catalogue as he was also, quite reasonably, assumed to be a pagan of some variety.

Everyone’s a satanist now. There’s a girl on TikTok this week who says masturbation is witchcraft. Kylie Jenner has been accused of endorsing ritual sacrifice after appearing in a makeup ad for her own line dripping with fake blood. There was a similar misunderstanding in Nathan Fielder’s series The Rehearsal : after Nathan performed a Salò -esque, Borremans-like, Balenciaga-mode shit-eating degradation rite devised by the child actor playing his imaginary six-year-old son, even though they were really just having some chocolate, his pretend wife in the show, Angela, complained that the practice was satanic, and her horror of everyday Devil worship went on to play a major role in breaking their make-believe family apart. If the loveliest trick of the Devil was once to persuade you that they don’t exist, it’s now to persuade you that they are absolutely everywhere, that they are inside of every image, hiding in plain sight right under your nose!

Even our culture wars are disappointing remakes of culture wars of the past.

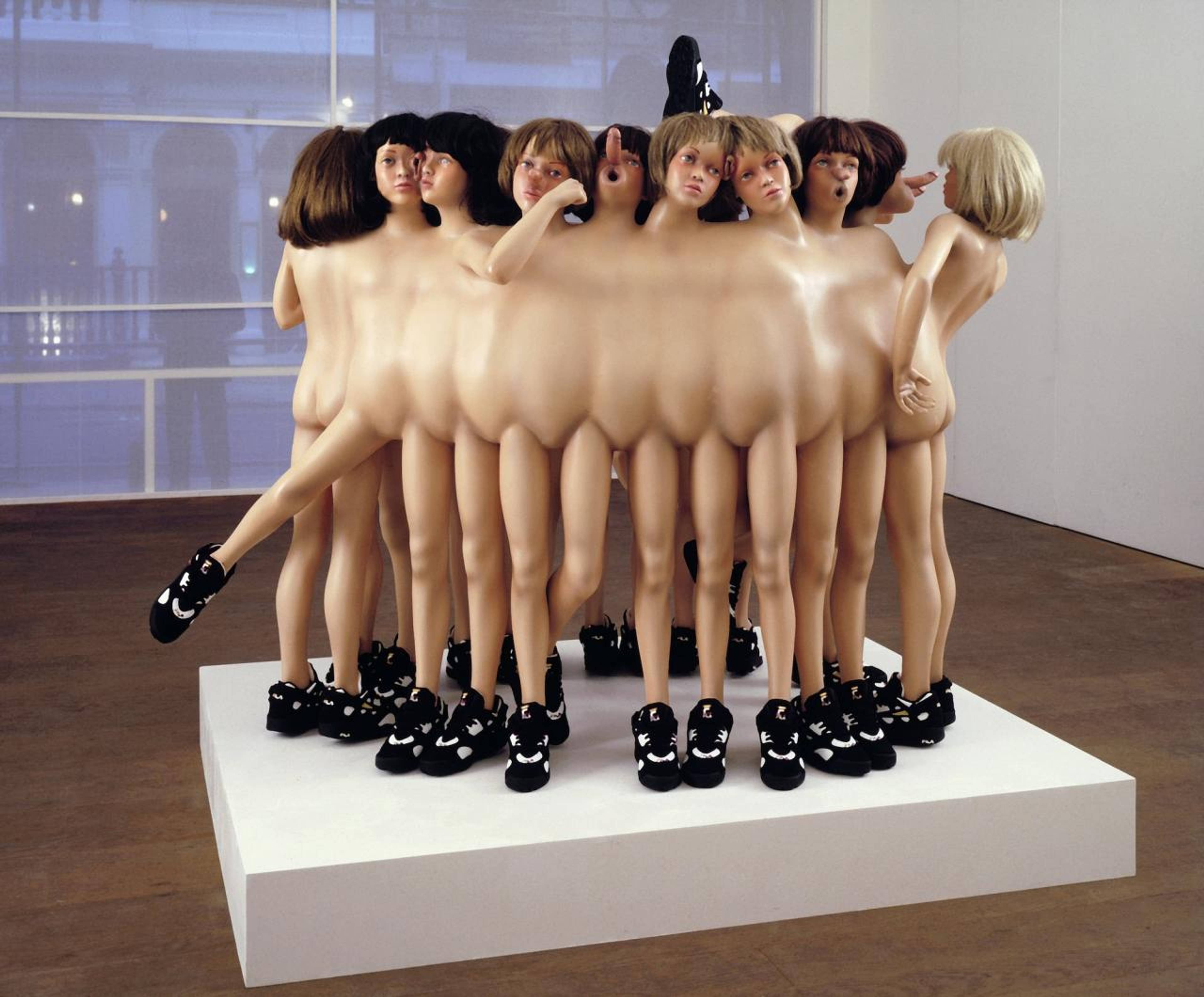

François-Henri Pinault, owner of Kering group, which includes Balenciaga and Gucci, was himself called out for Jake and Dinos Chapman sculptures having been previously sold at his auction house, Christie’s: or as Infowars calls it, the “Auction Site That Sells Child Sex Mannequins With Genitalia For Faces.” At the end of the 20th century, a cultural tipping point took place as ambitious media-savvy artists and curators, together with the tabloid press that they baited, spectacularized and commodified the immoral nature of art. The exhibition “Sensation: Young British Artists from the Saatchi Collection” at London’s Royal Academy intentionally stoked tabloid ire in 1997, particularly with Marcus Harvey’s portrait of British child killer Myra Hindley painted in children’s handprints; and then again at the Brooklyn Museum in 2000, where Mayor Rudy Giuliani described Chris Ofili’s painting The Holy Virgin Mary (1996) as “sick” on account of having elephant dung superglued to its surface, like a pair of Just Stop Oil protestors, and Jake and Dinos Chapman as “perverts” for said sexually mutated chimeric mannequins of prepubescent hermaphrodites with dicks for noses, vaginas for ears and assholes for mouths, joined together in many-headed metamorphoses. Those sculptures still remain some of my favorites.

Growing up in England I loved the Chapman brothers. I was thrilled by reading about “Sensation” in the Sunday papers and later by going to London with my mother to see its follow-up show “Apocalypse" at the Royal Academy, not understanding at the time that what I was admiring in those galleries was in fact the end of provocation, its emptying out and transformation into kitsch shock shlock and sensationalism. The outraged reception the Young British Artists courted led to transgressive art losing its edge and its cool in the 1990s, after which art could no longer upset us except by accident (as has happened with Dana Schutz, Sam Durant, and Philip Guston lately). Only now, more than two decades on, reactionaries – transgressive absurdist reactionaries, Alex Jones’s Infowars writers of all people – are again shocked, or pretending to be shocked, by exactly the same Chapman brothers sculptures as before; but they no longer think the Chapmans are perverts, they think they’re child-molesting necromancers in league with the New World Order. We have completed a full cycle.

Just as there was a major Satanic Panic before, in the 1980s, there was also outrage over these Chapman brothers sculptures before in the 90s. As n+1 ’s editors pointed out in their attack on the ugly present, nearly everything in today’s culture is a pale imitation of that which has come before, a copy of a copy referring to nothing that’s real. Even our culture wars are disappointing remakes of culture wars of the past.

When I was in England last month, Nigel Farage (the most effective British politician of recent times, who played a huge role in bringing about Brexit) was going around in his chauffeured car broadcasting videos denouncing Balenciaga and its collaborators as Luciferian nonces; but what he was also broadcasting, I thought, was the death of outrage culture, the end of performative outrage as the major driving force of culture it has been through these past six years. Once Farage and Alex Jones, and Tucker Carlson, the Daily Mail and the Sun are outraged about fashion and art, that has to be the exhaustion of outrage as a meaningful progressive position. One historical moment fades into the next.

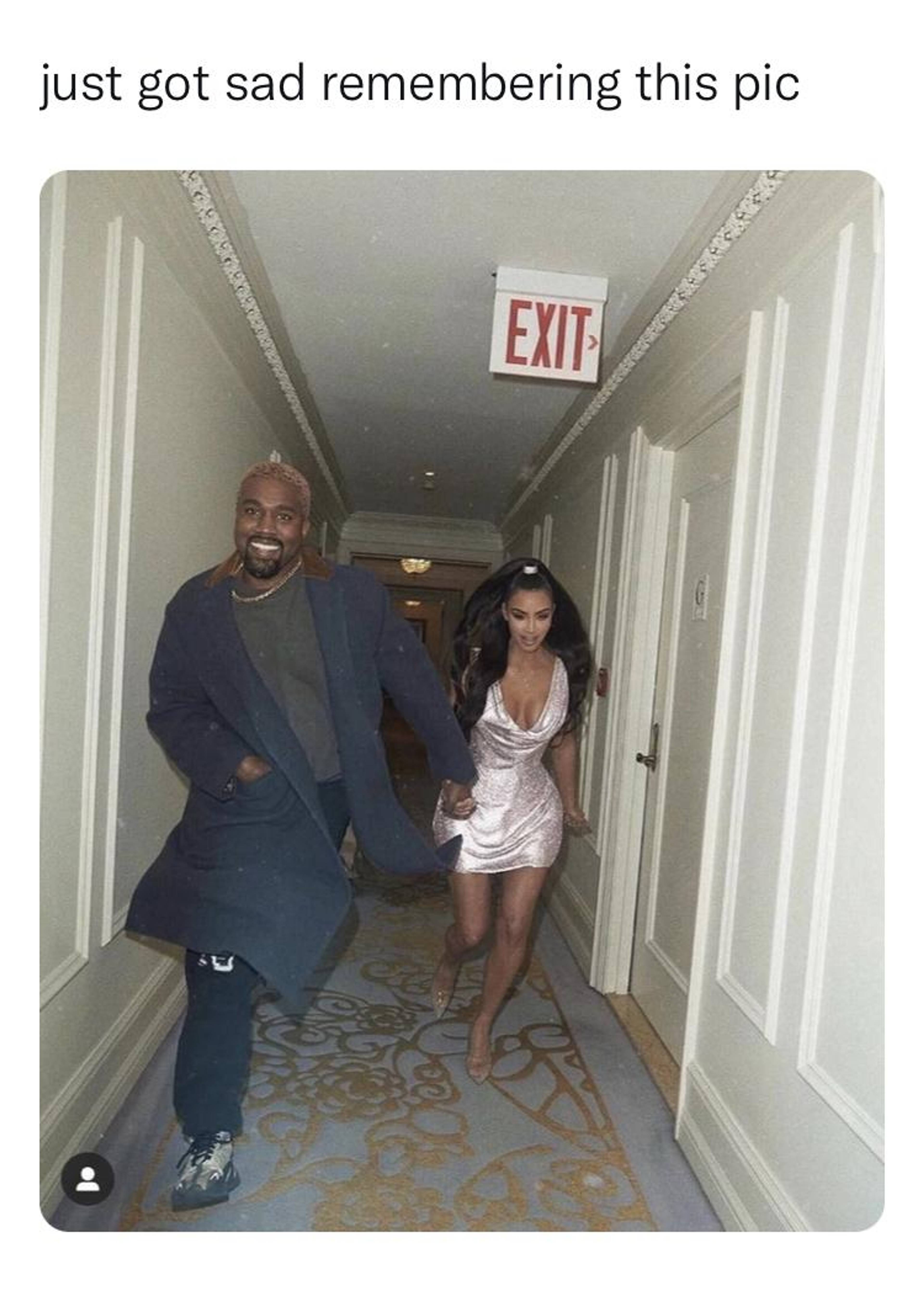

Jake and Dinos Chapman, Zygotic acceleration, biogenetic, de-sublimated libidinal model (enlarged x 1000), 1995

Writing about Kanye West feels like an appropriate way to end my column. It’s where I began: the first-ever column I attempted was for i-D magazine in London and was about Kanye and Virgil going to Milan and then later to Paris and trying to make it in fashion, very unsuccessfully to begin with (this was after i-D sold out to a massive publishing group, Vice Media, which I was pleased about at the time, and we were moved into their offices and encouraged to become star columnists; my effort’s not online anymore and the column only lasted a few weeks). The first piece I ever wrote for Spike in 2015 was about Juergen Teller shooting Kanye and Kim crawling around in the dirt on the grounds of Château d’Ambleville (all the pictures have disappeared and my sentences are as syntactically grotesque as an apology from Balenciaga’s CEO). I used to look up to Kanye so much and considered him the most visionary and ambitious artist of our time. The last time I saw him was this summer on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange, for the Balenciaga show, and I felt in awe of his presence. We have the same birthday, June 8; I wanted to possess just a part of his spirit. The last time I bought a magazine was 032c , earlier this year, so I could read Tino Sehgal’s interview with him (that magazine store on the corner by my house now has printouts of Bookforum ’s last cover taped up outside), in which he said, and I agree, “We can exist in a stronger, better way by coming together as artists and scientists to make our Earth the ultimate version of itself. Utopia is a heavy-handed word, but we shouldn’t be afraid of it. We should be trying to make Heaven on Earth.” He was a hero of mine.

Kanye is crossing every boundary and breaking every taboo for no reason I can discern, except perhaps that they’re there.

Kanye is a tragic hero. “Tragic” in the classical sense: of having, over the course of a life, had a great rise followed by a mighty fall, and of being completely responsible for his own destruction and downfall. He crashed his car late one October night in Hollywood twenty years ago, had his mouth wired shut, and set off on a wild trajectory that passed through most of the 21st century’s zeitgeists, all the way to the top and back down into the hole; amazing to behold really. Aristotle said, “A man cannot become a hero until he can see the root of his own downfall.” The root of Kanye’s downfall was believing in himself too much, and always voicing whatever was on his mind, whatever beautiful dark twisted fantasy. What I for so long appreciated about him was that he could not be restrained, that he was free – but that is also what has led to his unspooling, to his going so far beyond the pale and into, what exactly I don’t know: conspiracy and hatred, antisemitism, fascism, rambling unwatchable, unbearable interviews, nihilistic performance, ego, paranoia, monomaniacal delirium, madness, disorder, singing Hitler’s praises live on Infowars in a Vetements Fall/Winter 2018 biker jacket and black mask.

A couple months ago I spoke to a stranger, I think they’ve deactivated now and I can’t find them but they told me, “Even at his most contentious (before this recent slew), there was something I found refreshing about his logorrheic diatribes or ‘missteps.’ Celebrity has been mostly diminished to performative PR killspeak, and he remained, despite however big he got, completely candid and unfiltered to a fault.

But it was all a Goffman-esque performance of another kind, one that I sense became consuming given his unrelenting exposure to the world via paparazzi and social media, and I think it’s now approaching its logical conclusion.”

In his interview with 032c , Kanye told Sehgal about destroying his identity in a stadium in Atlanta last year. He was “doing a performance piece called The Funeral Rehearsal of Kanye West . … I have to always have the freedom of being disliked, so I can always be me. And so, this new piece is the death of Kanye West.

It is the death of the ego that separates us.

It’s the birth of humanity.

Let me start by killing myself.

The less you, the more room for God,” he said.

He destroyed his identity in the stadium and now appears to be destroying his reputation, his legacy, his businesses, his life, his dreams. He’s crossing every boundary and breaking every taboo for no reason I can discern, except perhaps that they’re there. He’s behaving more erratically and performing more madly and obscenely than some of the maddest and most obscene performers in the world: when Alex Jones is telling him to be less racist, telling him he’s just confused and doesn’t really admire Hitler, when even Trump is screaming at him over the table at Mar-a-Lago telling him he’s going to lose, he’ll never be his running mate, when Trump is now the voice of reason … that also means we’re at a point of change.

I saw a post on weird philosophy Twitter that said, “Kanye is overcoding all the flows right now. Disrupting all the sign regimes. Most people are not aware of what is happening right now.” Well, neither am I. But although I doubt he’s doing it deliberately, his recent appearances do further undermine the possibility of transgression and of outrage. He’s not speaking in codes, or asking to be deciphered, he’s blurting out the most offensive and dumbest lines imaginable. Nobody seems particularly shocked—just bored, exhausted, saddened, upset. Whatever their method or lack thereof, his performances are a hollowing out of the potency of fascist aesthetics, revealing again the figure of the fascist entertainer to be a pathetic clown, just a strange little masked portly goblin.

Found post from a private account, 2022

A Guardian columnist whose children have flown the nest embraces neo-nihilism. n+1 ’s editors cry out for beauty. Balenciaga renounces VIOLENCE AND HATRED MESSAGE. The color of the year is primordial invocation of joyous celebration. Kanye is a Nazi now, and he also has autism – OKAY? The lines are being redrawn in different places. The lines are pointing in different directions. We’re coming to the end of a weird and annoying cycle; or entering perhaps a whole new era of worse-yet derangement in which the boundary between fantasy and reality will collapse completely, and art and life will no longer be able to be distinguished from one another.

Maybe I … shouldn’t have ever thought Kanye was a visionary conceptual artist. Maybe I shouldn’t have been searching for crazed visionary conceptual artists and bohemian freedoms my whole life in the first place. Though I have moved from city to wonderful city and their respective artistic milieux, through fashion, art and literary scenes, I never do seem to meet the deranged, terrifyingly imaginative radical psychedelic sensualists who’ll lead me right to the edge, where I can no longer make sense of my own experiences, to ecstasy and transcendence, and finally complete doom; I never seem to meet such figures (save for maybe one cold Stygian night of ghost-hunting in a golf cart in the Hamptons with the artists Jamian Juliano-Villani and Billy Grant, who are the only truly free people I know), let alone a whole movement of them, consumed by rivalry, ambition, resentment and mania, driving one another ever on. I made it close to the center of the art world, close enough to catch glimpses of its peaks, and in my view there’s not a great deal going on there, at least not for me. Where are all the weirdos? I do believe culture was more interesting when it was made by weirdos, when artists and writers were ostracized by society, rather than celebrated, rather than seen as having an important role in upholding its standards and norms.

I often feel I’ve wasted my life searching for an imaginary bohemia that doesn’t exist anymore and may never have existed. But that’s not so much of a waste of a life; the search for bohemia, like the search for the great beauty, the blue flower, or the hard, gem-like flame, is just a way of chasing after an idea, just a journey nowhere. I have been chasing hazy dreams of bohemia and the transcendental experience for decades and though I have not found either, and likely never will, I do sometimes feel close, I have been able to experience life differently; and writing this column has been a very transformative part of my life.

Though we were told every day that everything was falling apart, I believe we’ll look back on this time period with fondness and nostalgia, rather than despair. I think it will seem deeply absurd and surreal in the mirror. We’ll likely forget about a lot that happened, or come to believe it never really happened at all. Here are the angels in the painted sky. Here are the soaring arias, the rays of light.

Leonardo da Vinci, Virgin on the Rocks (Paris version), 1483–86

___