After singlehandedly shooting down a group of Italian mobsters intent on murdering her, Tanya McQuoid tells herself: “You got this!” Tilting toward one side of the yacht, she slips and falls over the balustrade. We hear a loud thump against the dinghy attached to the side of the boat, before watching the empress descend into the calm depths of the Mediterranean. Silence. Death. Giacomo Puccini’s aria “Un bel dì vedremo” (One Fine Day, from Act Two of Madame Butterfly, 1904).

It’s a bitter and intense ending to the second season of The White Lotus (2021–), a show otherwise distinguished by the undisturbed decadence of its passive-aggressive communication and slow-paste narration. Though we knew one of its characters was going to die, I’d still argue that it would be naïve to view her death as a cathartic moment. The layered ensemble of anti-heroes in Mike White’s series paints a timeless fresco of subjects you’re embarrassed to relate to, enslaved as they are by their own narratives, faults, emotions, and, ultimately, self-interests. Rich or poor, figures from this ongoing wave of cinematic cynicism (see also: The Triangle of Sadness, Don’t Worry Darling, White Noise, Parasite, The Favorite, The Bling Ring etc.) are caricatures of a narcissism too normative to even stand out.

Moralists interpret the ancient tale of Narcissus as illustrating the perils of exaggerated self-love, but that is categorically a cheap take. Narcissus didn’t drown because he loved himself to the point of literal self-penetration; he drowned because he lost the ability to differentiate between himself and the image of his own reflection. Tanya McQuoid’s death is downstream of losing her balance; she lost her balance because she didn’t take off her heels. She, too, couldn’t distinguish between a “self” and the projection of her own narrative, falling from a boat before daring to fall out of character. In a pivotal moment, the costume wasn’t laid aside.

Tanya McQuoid (Jennifer Coolidge) in Season 2, Episode 7 of The White Lotus, 2022

As protagonists, their common cause of death – McQuoid’s body resembles the drowned, even if she was dead before she hit the water – is what makes them tragic instead of merely pathetic. Tragedy, an artform deriving from ancient Greek rituals, is defined by its involvement of the audience to the extent that they feel the hero’s closing-act downfall is partially their own fault. It could have all gone so differently, but their hero didn’t see something that the viewers could: no intervention was made to circumvent the dagger’s sleight; another one bites the dust. It’s never death itself that makes people shiver, but the privileged, panoramic view that exposes subjectivity for what it is: oblivious and hardly ever transgressed.

Tragedy reminds us of the truth we tend to forget in our own self-involvement, the truth that free will can only take us so far along the way.

In a way, it’s not just a genre. Animated by a singing chorus, figuratively and literally, tragedy is the first historically known instance of people playing themselves. It might be the closest we’ve come to materializing a primal truth, one that rests just outside our cognition’s reach. This is how we came to understand art today: as an attempt to materialize something one cannot fully conceive of, to search for the unthinkable in expressions of all forms, to unearth it from within our very selves.

Rationality and reason are strategic lies we tell ourselves, because everything else would be too much to handle.

Friedrich Nietzsche’s The Birth of Tragedy (1872) explains the will to such a persuasion as a dialectic between two seemingly opposing – but actually harmonious – energies of creative intuition. Deriving from Greek mythology, the Dionysian and the Apollonian are typified in the present day in Berlin by Berghain and Gropius Bau. The former is a world of intoxicated selflessness, of symbiosis between place, time, and artform; it constructs a lived experience that is as real and consequential as it is alternative and fleeting. Conditioned by its own expiry date, Berghain is a violent decadence that constantly reinvents itself.

By contrast, and despite its institutional allure and imposing architecture, there’s nothing truly decadent about Gropius Bau. Its vast, neoclassical walls house alienated art objects like prisoners under the gaze of security guards, ticket venders, state subsidies, and a hymn of silence, with a hollow legitimacy that mimics a shadow theater of societal pretense. Gropius Bau, here a stand-in for the state’s grip on the representational role of “high” culture, considers itself an heir to the Enlightenment, when really it is a child of the guillotine.

Therein lies the logic: The Apollonian sense of image and clarity, a make-pretend projection, will always be animated and enabled by the chaotic Dionysian reality beneath its facade. Rationality and reason are strategic lies we tell ourselves, because everything else would be too much to handle.

The atrium of Gropius Bau, Berlin

In the manifesto Superflat (2000), Louis Vuitton pop-up artist-extraordinaire Takashi Murakami repeats what so many other post-modernists before him said, that appearances and images make the world go round. If the aesthetic of flatness is exaggerated in images, it is only because we acknowledge a supremacy of appearances in everyday life, erasing the differentiations we had previously invented and relied on, between self and other, fine art and entertainment, artistry and daily life, etc. In a world of the Image, things and their meanings are more plastic and interchangeable, more prone to ruptures and easily glued together than ever before, begetting – as in tragedy – an ethics that depends on loose narrative framing.

Twenty-three years later, I get the feeling that the act of allusion has replaced the act of expression. Day by day, we rely on a subtext that either vanished or never existed, collectively waiting for someone else to fill in the gaps of what we thought we meant to say. Overstimulated and still bored – ahh hell – even the clearest of images have become too much to bear.

Because the more we try to deny it,

the more we become aware,

that behind all representation

lies an empty vessel of despair.

View of “Takashi Murakami: MurakamiZombie,” Busan Museum of Art, 2023

It sucks to understand that the collapse of narrative control, the urgency in yearning for cohesion, and the uncertainty about what is and isn’t real are pains not wholly conjured up by critical theorists afront a backdrop of dysmorphic capitalism. Indeed, these anxious inconsistencies faze us because they were always mute participants in a kind of group chat: Nature is indifferent, objectivity unnecessary, the world chaotic and tragic; we never got and never will get a grip on it anyway.

The project of modernity can be understood as a collective quest at making sense. But for all our struggles and technical advances, we have achieved the precise opposite. Becoming as flat and as free as the icons we once worshiped, we’re extremely self-aware, yet totally unable to distinguish ourselves from our surroundings.

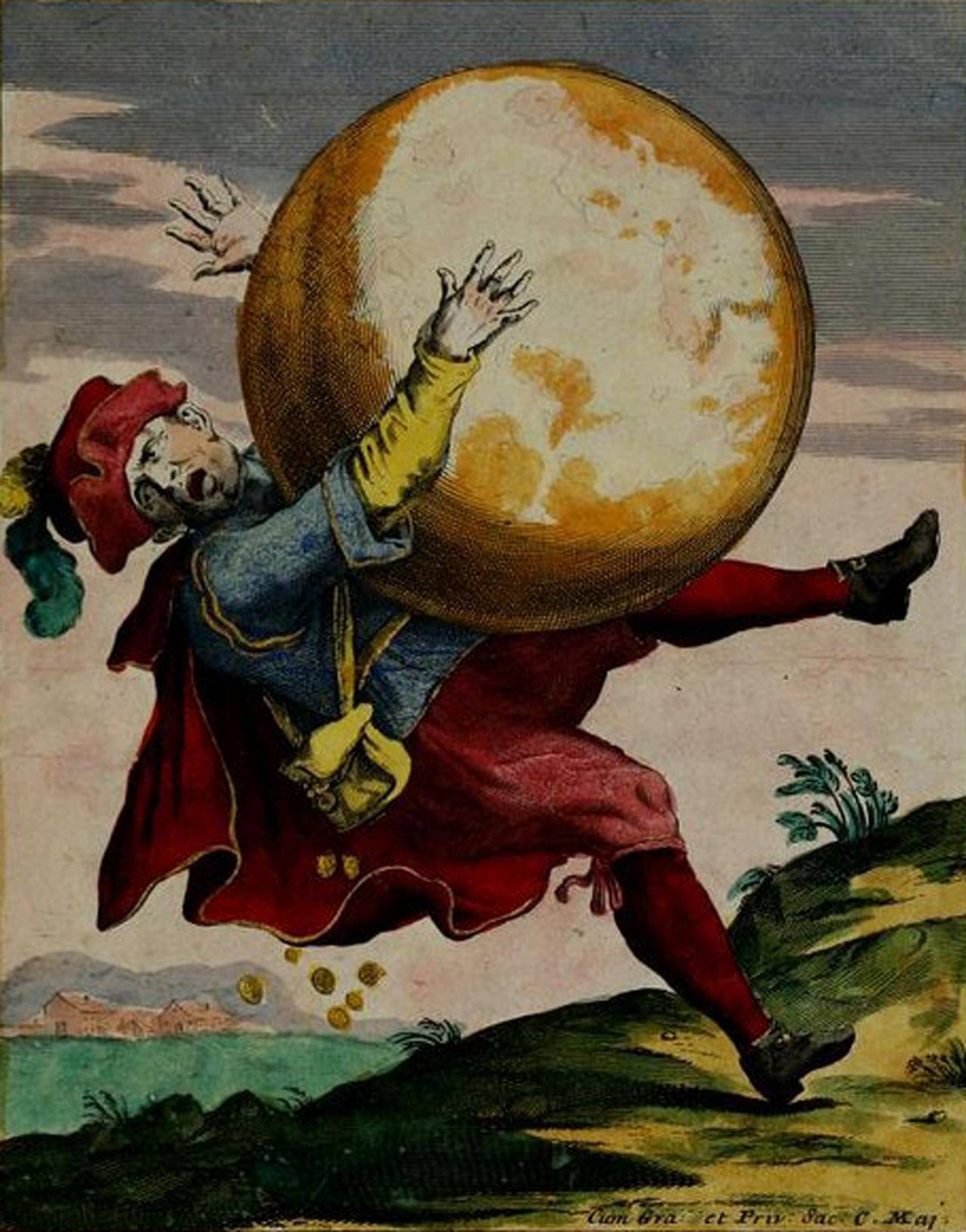

Giuseppe Maria Mitelli, illustration from a book of Italian proverbs, early 18th century

___