There is a classical way of conceiving artistic production based on a circular conception of time, where everything is repeated endlessly, a neverending story trying eventually to reach its own essence. A time that never ceases to turn around a fixed and eternal point: a motionless future.

Epistola de Secretis Operibus! It’s time for magic.

We would like to consider the boliw. Neither bulbous nor heavy, these often buffalo-shaped ritual objects leave a sense of overfullness, even a hyperreal quality, with the shape augmented or marked as though with an especially intense form of perception. Boliw come from Bamana villages in Mali, where they are handled only by those who have undergone a decades-long initiation process, adding materials such as mud, hair, blood, wood, tree bark, roots and other substances in ritual practices that change the boliw over many generations. Each boli is a collective creation, recording the investment of the efforts of a large group of people over time. It contains multitudes, and yet has become even more itself. It mediates the visible and the invisible, magic and the material world. The object ages and grows each time it reappears. A boli is alive.

The third season of Twin Peaks shares a number of qualities with a boli. It is most legible as a recording of memory over time. This necessitates a certain slowness – perhaps the televisual equivalent of thickness. Lynch returns time to television. In the frenetic and decadent atmosphere of most TV, no matter its subject matter, the cuts come quickly with the deadening rhythm of a con-man’s patter. Some directors occasionally puncture this rhythm with a self-consciously “masterful” extended tracking shot. Lynch, meanwhile, gives us five long minutes of a man sweeping the floor in a bar, the camera locked on a tripod. There is all the time in the world, he reminds us, rather than a hyper-stimulated now. He returns us to the sense that this is all a fiction, even if it is one into which the world itself seeps through.

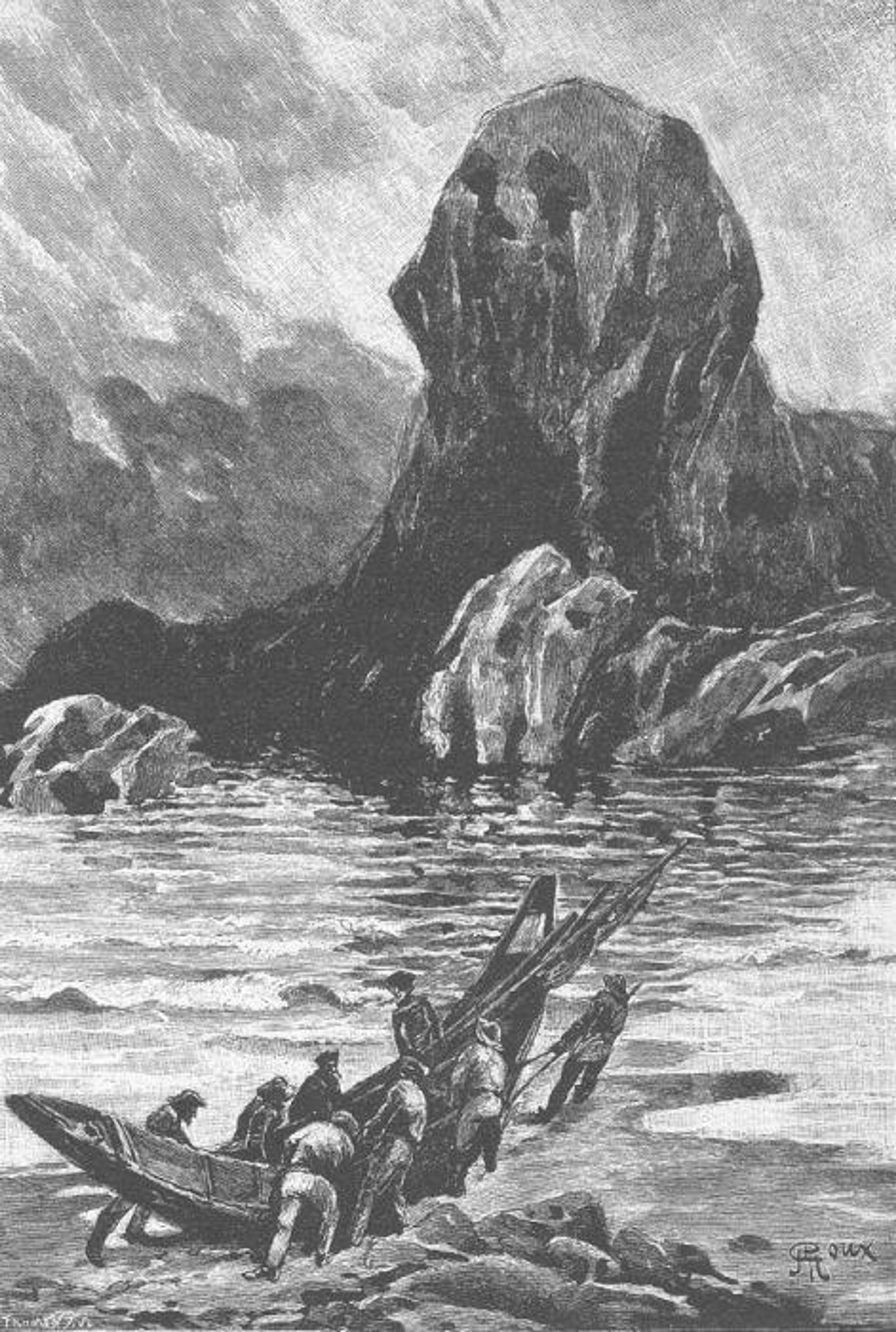

Illustration by Georges Roux for Jules Vernes' novel Le Sphinx des glaces (1897)

The third season of Twin Peaks also has an accretive element, an element of collective production. There is an excess of plots, characters, locations and events. A lack of motivation, a surfeit of clues. Most characters are not designed to survive, and they give up their ghosts easily, almost blandly. The concerts that close each episode are a part of this accretion. A curatorial selection, they include current LA bands, actors from the show, Eddie Vedder and the Nine Inch Nails. This heterogeneous selection blurs the line between the show’s universe and ours, which cannot be held apart.

With fictional characters turned real, Lynch opens the gate of our world to them. In the multiverse there is a world where Laura Parker aged. It’s our world, and in our world Laura can’t remember what happened in the other. We are dealing with a new form of editing that is not the manipulation of diegetic time and space. Characters have aged twenty- five years because indeed twenty-five years have really passed. It’s about editing our memory.

The ancient Greeks, to whom a trained memory was of vital importance – as it was to everyone before the invention of printing – created an elaborate mnemonic system based on a technique of impressing “places” and “images” on the mind. To remember is to connect events to a topography.

Twin Peaks offers a topographic map.

In this map, we notice the forest has grown in importance.

Networks of trees now have a dynamic presence. While the original opening sequence showed the town’s sawmill, the opening shots of the new series simply rest on the trees, as an enveloping texture. Even inside the mythic space of the red-curtained lodges, there are now (sentient) trees. This new awareness of a multitudinous subjectivity emanating from the world seems to come with a fatigue with residing solely within the world of humans, a boredom with their petty, tragicomic foibles being the only story.

Boli, late 19th – 20th century Photo: Brooklyn Museum

There is a deeply forlorn quality of life in this show. The old show had this too. Through forced cheer and the dead rituals of Mom and Dad, Christmas presents, etc., the home never functioned properly, except at certain shining moments, like Major Briggs’s speech to Bobby. The new season’s characters wander around aimlessly, their lives determined by accidents and chance, watching screens. Only a few old-timers seem capable of any action. The characters wander in search of a plot, expressing their essential traits. Laura is heroic; Cooper is good; Audrey is confused. Some characters seem to have changed their arcs; many others are stuck in holding patterns. Sarah Palmer, Laura’s mother, is stuck on repeat most horrifcally, as she sits at home watching lions maul their prey on TV.

That home and that flat-screen TV belong to the real-life occupants of the Palmer house, in Washington state. The occupant of the house, one Mary Reber, herself appears in the final episode. The show has literally incorporated the world, which has itself been influenced over twenty-five years by the original show, into its fiction, which was produced by the world in turn.

Cooper sees Sunset Boulevard and hears the words “Gordon Cole”: the character from the lm Sunset Boulevard and also the name Lynch gave his own character on Twin Peaks. Twin Peaks: The Return contains almost everything in Lynch’s universe. It is an anatomy of his obsessions and influences, other movies, intertexts. You could make a list of every Lynch work and find an analogue to it in the show. It is an opus and a compendium. But still more, it is a measurement of the effects of time on a shared fiction. In so doing, it beckons to another timeplace, which is neither in “fiction” or “reality”, “past” or “future.”

There, perhaps, there is a clearing.

Like Laura Palmer, found recently on Earth, we are all aliens. Creation is not simply a repetition of the logic of expense, of dissolution or spending of the self, but an opening of ourselves to the possibility of new contaminations, a complicity with the outside, becoming alien. We all share in a dynamics of alienation within a cosmic continuum that does not cease to split and reabsorb its splits. The series never ends.

PHILIPPE PARRENO is an artist based in Paris.

ASAD RAZA is an artist based in Leipzig and New York.

– This text appears in Spike Art Quarterly #54 and is available for purchase at our online shop –