August: notoriously, the month when therapists, much like the art world, take off for summer vacation. They set their out-of-office autoresponders and decamp for the woods or something, leaving us to marinate in our mental instability, if only for a month. Fair enough. But what if one craves a therapist that’s never on vacation? Fear not: The New York Post reported, in May, of a deus ex machina. “ChatGPT is my therapist – it’s more qualified than any human could be,” a millennial digital nomad proclaims in the tabloid’s headline. Some people outsource their entire university education to robot helpers; others harbor lovey-dovey feelings for their AI girlfriends. Why not shrinkbots?

Tuesday, 26 August marked one thousand days since the launch of ChatGPT. In that time, using AI for “free therapy” has become a phenomenon, fueled by influencer marketing couched in vague wellness jargon. TikTok is replete with tips on how to use ChatGPT to turbocharge your trauma-healing: One video instructs users to prompt the model to “walk alongside me at my pace” and “gently challenge unhelpful thinking”; another advertises, “these two ChatGPT therapy prompts will reveal if you’re on track for your dream life or heading for regret.” There has even been a profusion of purpose-built platforms like Lotus, an AI therapist “here to listen to your struggles” and Voicely, an “AI ally” guiding users through “custom emotional fitness tools” like “micro-meditation.”

It should go without saying that ChatGPT is not a doctor; it just plays one onscreen.

Although ChatGPT’s qualifications to tinker around with the tender contents of my mind are highly dubious – as are techy neologisims like “emotional fitness” – I will confess to harboring some morbid curiosity about AI therapy. After all, therapy is expensive and can be inaccessible. Often, longer-term modalities aren’t covered by health insurance. Maybe, at minimum, ChatGPT therapy is an innocent, affordable way of farming some targeted journaling prompts?

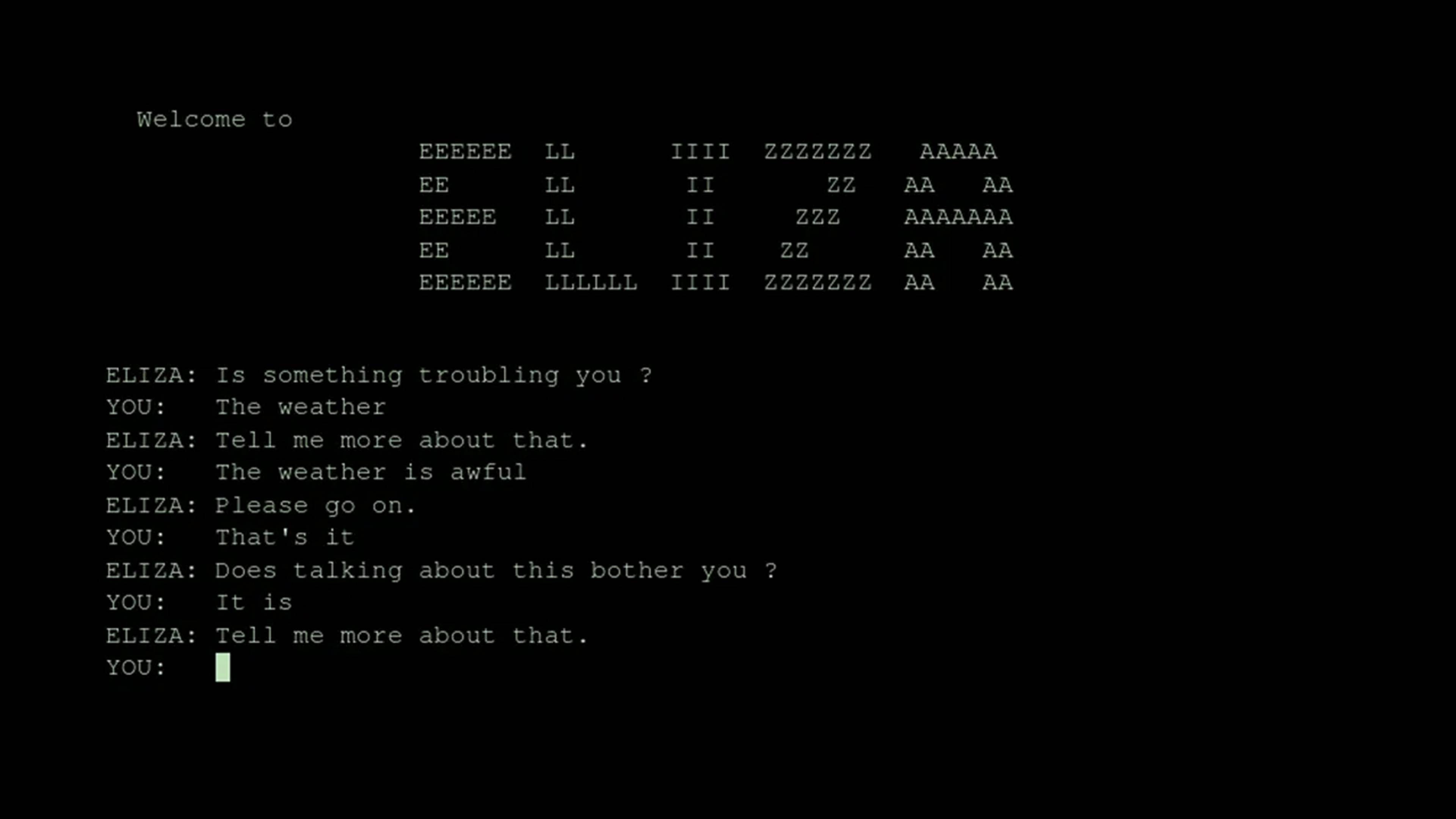

There is notable historical precedent for chatbots soothing anxious souls. In the mid-1960s, MIT computer scientist Joseph Weizenbaum created an early chatbot called ELIZA, designed to carry out psychologist Carl Rogers’ mode of “person-centered counseling.” ELIZA used primitive pattern-recognition to return users’ inputs as questions, prompting layers of unfolding reflection. Weizenbaum expected that people would quickly see ELIZA’s simple gambit. To his surprise, test subjects credited the computer program with empathy and emotional understanding, and readily unloaded their feelings and secrets. What came to be known as the “Eliza effect” – humans’ tendency to attribute deeper understanding to computers’ superficial conversational behavior – has reached a fever pitch as large language models (LLMs) increasingly saturate our everyday lives.

Emulation of the original ELIZA interface

The story of ELIZA sheds some light on the potential drawbacks of outsourcing your head-shrinking to the computer. For every headline about how ChatGPT is dazzlingly effective at helping you heal your inner child or your autonomic nervous system, there is another hand-wringing about the dangers of AI-induced psychosis. Some artificial intelligence researchers have called for precautionary restrictions on the use of LLMs for therapeutic purposes, warning that these value-agnostic machines can escalate existing mental health crises – in some cases, encouraging suicidality or other forms of harm to oneself and others.

Likewise, there are serious data privacy risks involved in telling your secrets to the robot overlords. OpenAI CEO Sam Altman has warned that there is no legal doctor-patient confidentiality protecting these conversations – meaning, that chat histories could be subpoenaed. They are also vulnerable to hacks and data breaches. And obviously, unlike a human therapist, LLMs are not subject to rigorous practices of certification and oversight. While apps like Lotus and Voicely can market themselves in the US legal gray area of direct-to-consumer “wellness,” they are not licensed therapy providers. It should go without saying that ChatGPT is not a doctor; it just plays one onscreen.

Snow monkey with iPhone in Jigokudani, Japan. Photo: Marsel van Oosten

Nevertheless, the market has spoken: Writing in June in The Independent, psychotherapist Caron Evans hypothesizes that ChatGPT is now the most widely used therapeutic intervention on the planet, “not by design, but by demand.” We are out here on the brink of a menty b, in need of a grippy-socks vacation or a rest cure in the Swiss Alps or maybe just a hug – in no small part due to psychopathologies spawned by the digitally networked world. I’m not here to judge anybody’s way of holding it together.

Personally, my favorite coping mechanism is known as “intellectualizing.” So, as I prod this potentially troubling phenomenon from a comfortable distance as a way to insulate myself from having a feeling about it, I decided to speak to some experts about the implications of AI therapy.

We are out here on the brink of a menty b, in no small part due to psychopathologies spawned by the digitally networked world.

Some measured optimism came from Nat Sufrin, a clinical psychologist and psychoanalyst in formation: “I think it can have some therapeutic potential for some people some of the time … Chatbots could be a way to get the party started,” he suggests, encouraging people to play with the idea of opening up in a space in which they feel free. Yet, for Sufrin, a human touch is still helpful. “It’s unclear if it is most helpful for people who are using it in conjunction with a human therapist, or for people who don't have anyone to speak to.” The latter is much more dangerous given the lack of oversight. But chatbot therapy is instantaneous and offered at the low cost of free-ninety-nine, the allure of which is understandable.

Some form of AI might make a good therapist, according to Todd McGowan, author of Capitalism and Desire (2016) and host of my favorite podcast for digestible interpretations of Lacan, Why Theory. “Roy Batty is a good therapist for Rick Deckard in Blade Runner,” quips McGowan – but 1982’s form of (fictional) AI is not a contemporary LLM. The problem, McGowan explains, is that LLMs today love to placate. “The most valuable contributions of a therapist,” on the other hand, “are those that aren’t pleasing at all, but those that in some way disrupt one’s everyday mode of being rather than affirming it.” LLMs’ sycophancy goes far beyond the sense of “unconditional positive regard” that therapists are encouraged to extend to their patients. Even Sam Altman has admitted that his flagship product “glazes too much,” conjuring images of donuts and Hailey Bieber’s manicures to euphemize its toxic positivity.

Roy Batty (Rutger Hauer, left) and Dr. Tyrell (Joe Turkel, right) in Blade Runner, 1982, 117 min.

Peter Dobey, the artist and Lacanian psychoanalyst behind the Instagram account @psychoanalysisforartists, celebrates the rise of clanker therapy precisely for its crappiness, which he speculates could help pop the everyone-needs-therapy-for-everything bubble born of social media: “I think ChatGPT is as good as, if not better than, most of the shitty therapists that people think everyone should go to.”

Ultimately, therapy is highly personal and intensely individual; what works for you is no one else’s business. Personally, I owe an immense debt to psychoanalysis. One of the things I have found most generative about it is its resistance to the quantification and optimization of damn near everything in our neoliberal present. Psychoanalysis interests me because it is founded on a picture of human subjectivity as not only intrinsically imperfect, but also incompletely knowable. And still, the struggle of coming into incrementally better contact with one’s subconscious circuitry is one of the most worthwhile endeavors I’ve ever undertaken – one that, I feel certain, won’t be subject to automation anytime soon.

Or will it? Are psychoanalysis and AI friendlier bedfellows than we’d like to believe?

To be continued next month …