Once, after taking the train all the way from Berlin, I sat slumped in the back of a black cab, en route to Whitechapel Gallery for the London Art Book Fair. In Shoreditch, staring sleepily out the window, I was a little bewildered to see a huge billboard with a serious, high-cheek-boned model, with the words Saskia, Jonas, Neukölln, Berlin. 10am. Surely, there aren’t that many twenty-somethings who wear Hugo Boss in Neukölln, I thought. But then, the lived facts of a place are often abused when it comes to selling the perfected idea that place promises. And it seems like Berlin has long been ripe for such abductions and diffusions, because Berlin has worked hard to become its own series of edgy memes. Berlin is a shorthand then – but for what, exactly?

Vincenzo Latronico’s bestselling novel Le perfezioni (Perfection) deals in just this idiom, that of the ideal Berlin life and the tension between how it’s presented and its actual, lived reality. First published in Italian in 2022, it got its German and English translations – as well as a shortlisting for the International Booker Prize – in 2025, a year that’s seen Berlin’s art scene more divided and defunded than at any juncture since its reunification. This novel deals in nostalgia because, from across the rupture of an international creative class’s discovery of German Staatsräson – which treats as a national responsibility the security of Israel, up to and including against criticism – and a post-urban shift that has seen a lot of millennials reevaluating their relation to city life, and all of this underpinned by the rising cost of living, Berlin today is not what it once was. Of this, it’s safe to say, we can all agree. Plus ça change.

Latronico makes it clear that his is an update of George Perec’s 1965 novel Things: A Story of the Sixties. Instead of Paris, waning as the center of European cultural production pre-1968, we get Berlin, grappling with the delights of the post-Wall city, its protagonists “that unlucky generation” who become adults in the years after the Great Recession (2007–09). Anna and Tom are a perfectly nice couple, who don’t necessarily yearn for things in themselves, but for perfected images of these things. As graphic designers and web developers, they live and work in the creation of such images: “just as the visual points of difference they sold to their clients were also sold to thousands of others by creative professionals all over the western world, an identical struggle for a different life motivated an entire sector of their generation.”

Told in a generational collective pronoun, which brings to mind Annie Ernaux’s hybrid memoir The Years (2008), we follow our protagonists as they migrate to Berlin from somewhere in the south of the continent – Italy, presumably, but just as easily Spain, Portugal, or Greece. As characters, they’re kept purposely vague – ciphers somewhat, or archetypes. Having grown up internet-savvy, they become freelance professionals, making a home in Neukölln with an “open-end lease for the two bed apartment in Reuterkiez secured by forging an employment contract they found online.” What follows is recognizable to anyone who has moved to Berlin in the last two decades: a leisurely life of culture and socializing with a widening cast of characters, drawn together not only by the cheap rents, but also the distance and freedom from their homeland traditions necessary for making art.

Now is a time of people leaving Berlin, and not in a quiet way. Post-Covid, those who exit stage left often seem to have turned “against Berlin.”

By the end of the novel, Anna and Tom’s scene has shrunk once again; people have left because “the life they had been building for years would prove too vulnerable to collapse. An eviction notice would land on their doorstep and the Mieterverein would be powerless against the Eigenbedarf” (a provision that allows landlords to evict people to move in a family member, whatever the objections of the tenants’ union). Latronico is great at stacking up these details of life in Berlin to the point of poignancy, even for those readers who have lived them. His characters are weirdly every-people: a middle-class, art-world-adjacent, cis-heterosexual couple who just like nice, pretty things. They leave Berlin for adventure, only to wind up spending an inheritance opening a guesthouse in the south of Europe, going into the business of promising people lived moments in perfectly imagined interiors.

Reading Perfection, you realize that Berlin has tried hard to stem the onset of neoliberal sclerosis, but as every last piece of empty land is developed, it has not always succeeded. Sure, Airbnb is largely banned, but the federal Zweckentfremdungsverbot allows the setting of widely disproportionate rents for “furnished temporary apartments” – a decidedly Anglo-Saxon phenomenon in a city where flats usually come with no more than an oven and a sink – meaning, that new arrivals face different expenses entirely from those who moved here, like, yesterday. @Berlinauslandermemes makes fun of us for advertising our homes to rent for two-and-a-half summer days for two hundred euros, but we do so because some of us have no other choice. Latronico himself, on such serious matters, is no less funny: “gentrification, a term used almost exclusively by the people who caused it” and which was “as they understood it, [...] something other people did.” Humor, after all, is all we have when discourse elsewhere has become so pious and indignant.

Memes and the accounts run by the people that make them have become part of the visual culture of our time. Artist Cem A.’s @freeze_magazine is not just parody; it’s succinct institutional critique. Latronico’s novel is itself a meme the more one considers it: the focus on image production and the effect of the internet on the formation of opinions, entire lifestyles, and the use of the city as a prop to document them all. And we’re all the more appreciative because, by updating the template laid down by Perec, it neatly sums up the dislocation of the Berlin expatriate life of the last twenty years.

Like Anna and Tom, my own brain is ravaged. Just writing this is hard, because I’m constantly jumping out of the document and onto another program, in search of dopamine and distraction. Berlin itself has often felt like a place where your mind wanders after you’ve spent enough time here: The comfort and mindfulness (and I use the word on purpose) that spring and summer in the city can give rise to are very real, and I imagine it has saved some people; but once that passes, one either gets down to work, to making art, or one’s attention drifts to other places, to “home” or wherever the real money is.

Many have come up against a logic that is not part of their shared “historical reality,” their resulting dissent met with scandalous repression.

Now is a time of people leaving Berlin, and not in a quiet way. Post-Covid, those who exit stage left often seem to have turned “against Berlin.” Indeed, Anna and Tom are in danger of becoming like those people Régis Debray, in his masterful little screed “Against Venice” (1995), called “people of taste,” lovers of art as lifestyle, shared memories as perfected reality, “those whom works of art render blind and deaf to commonplace historical reality.” Berlin, in such light, becomes an illusion of personal freedom, oblivious to the world of mortgages and middle class responsibility.

Many artists didn’t move to Germany when they moved to Berlin, but to what one friend of mine called a “cosmopolitan nowhere.” Such disregard is bound to result in disorientation, if not eventual bitter disappointment. Anna and Tom, and indeed so many of us, never noticed the fluctuations of people coming and going, “because that limited world regenerated fast enough to give the illusion of infinity.” Until such time that it didn’t. “As they moved closer to their mid-thirties, their friends, even the old-timers, would suddenly decide to move back... but back where? They would use the term ‘back home,’ surprising even themselves that Berlin was not it.”

Which brings us to political engagement and how, for many, “back home” increasingly means a different politics. A year before Brexit and Trump, Alan Kurdi, a two-year-old Syrian boy, was photographed drowned on a Turkish beach, jolting Anna and Tom out of their self-made, hipster presentism and into a volunteer center for refugees. The historical reality Latronico paints of the ensuing migration crisis gives an accurate picture of how the city’s international scene can be mobilized to join the causes of liberalism. They’re part of a group who meet regularly in a studio on Hobrechtstraße, eager to do something. As he describes the mismatch of the couple’s skills with their ethical impulses, so perfectly voiced on social media, and the diminishment of their engagement in light of Gallery Weekend and the Biennale, I don’t read Latronico as satirical or cynical; if anything, he seems poignant for a moment that’s passed, “a specific time and place” with people doing the best they could – one later mirrored in the arrival of tens of thousands of refugees fleeing Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

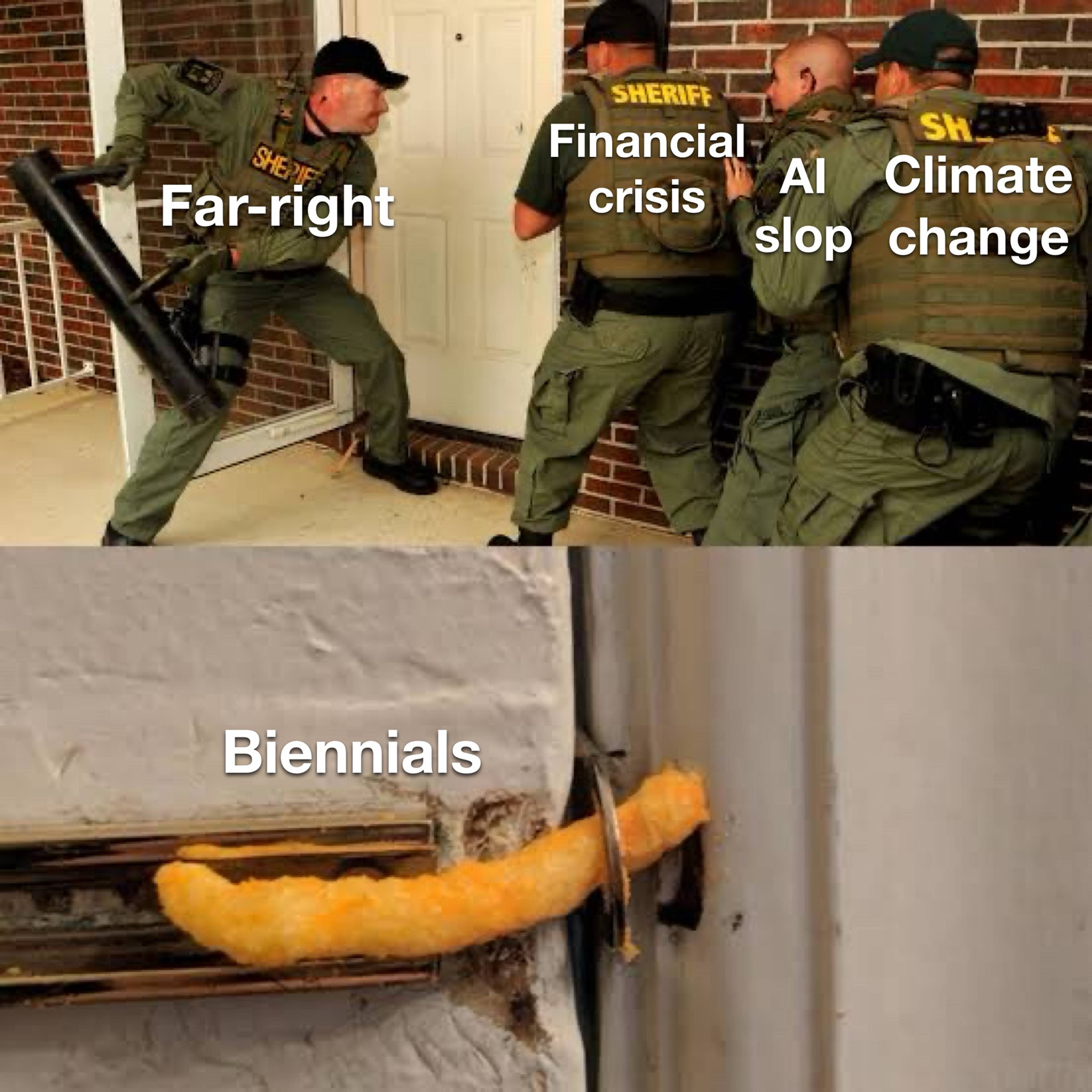

While the international scene could look to German leaders for guidance on how to do politics in 2015 and 2022, in the time since 7 October 2023, many have come up against a logic that is not part of their shared “historical reality,” their resulting dissent met with scandalous repression. Taken together with slashes in funding for culture by a new rightwing local government – amounting to a 12% year-over-year reduction for 2025 – what was once an environment that facilitated art and imaginative dreaming, unmoored by national traditions, has become, for many, something of a potemkin village. The dream seems to have morphed into a grotesque and unwelcome place at odds with many individuals’ conceptions of freedom and human decency.

It now feels like the perfect life sought in the novel could only be allowed in hindsight, yellowing in the past tense, against the backdrop of so uncertain a future.

Sometimes, I feel like we all forgot that, way back in 2010, Chancellor Angela Merkel declared, with Beckettian flourish, multiculturalism’s utter failure (Der Ansatz für Multikulti ist gescheitert, absolut gescheitert). Anna and Tom could integrate as much as any other white, EU-passport-holding immigrés, but reading Perfection in 2025, and sensing the jadedness of the art scene, the violence of the police state against those doing the only honorable thing one can do in the face of genocide – protest – and the rise of an organized far-right, you can’t help but realize that it was all, indeed, a sort of illusion. Or, at the very least, something confined to history. Perfection is a lampoon, because it now feels like the perfect life sought in the novel could only be allowed in hindsight, yellowing in the past tense, against the backdrop of so uncertain a future.

This past May, I visited an exhibition by Andy Fitz that paid homage to those artists, those image creators, who have been organizing themselves in a state environment that would seem to no longer welcome their political, and by inference, their creative, engagements. It took place on the very same Hobrechtstraße, at GUTS, one of the project spaces that feed the art world in an earnest way, and which are most threatened by rising rents and funding cuts. (Indeed, following months of insecurity about the extension of their lease via Berlin’s Association of Visual Artists, GUTS moved out at the end of June.) Titled “7PM,” Fitz’s sculptures and sound piece depicted the aftermath of a meeting: some elongated, stacked, and deformed chair sculptures, broken glass vases with dying flowers, the notes upon which are extracts of The Index of Repression, a database of German reprisals against solidarity with Palestine since 2019. In the whispered susurrus coming from behind the curtain, we hear the activist meeting: If we edit and plan our speech, it arrives stagnant … Individuals just don’t make real change, it’s a false logic that leads people to think that virtue signaling is enough because someone else will save them.

___

Vincenzo Latronico’s Perfection (2025) is published in English by Fitzcarraldo, translated from the Italian by Sophie Hughes.