“Helping People” left me puzzled, but that’s not a bad thing. The six paintings’ muddy grounds and dayglo-bright surfaces reminded me of crayon etchings, where a dark surface (usually, black crayon) is scratched off to reveal the garish color behind it. All the better to highlight the intersocial concern of these philosophical works: people in states of care, helplessness, or commitment.

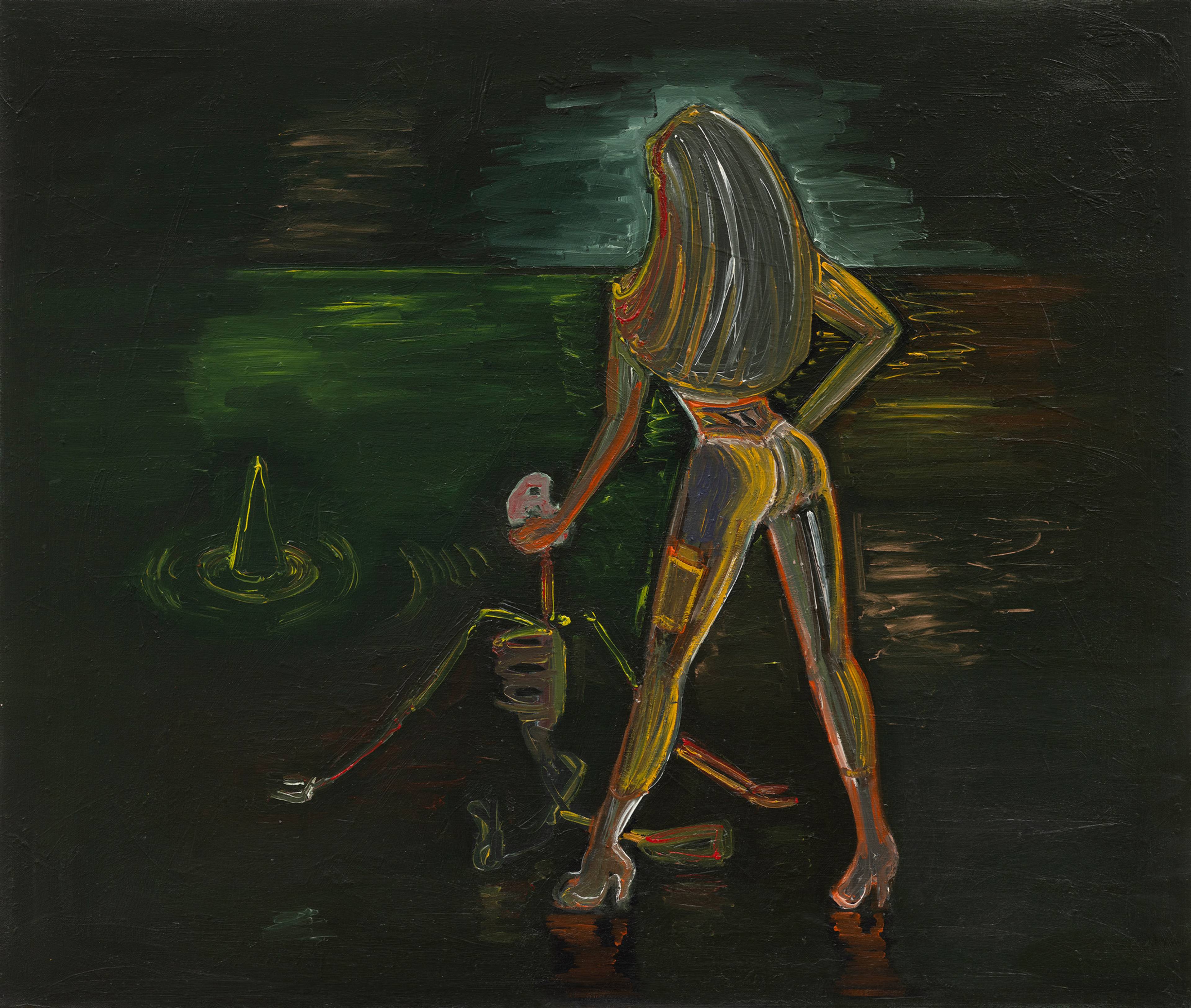

Through a careful use of geometrical, almost Cubist color, Lise Soskolne’s (*1971) figures become nearly archetypal: faceless, defined only as functions of their roles. In A Witch Hunt (all works 2023), a dominatrix-like figure in heels (seen from the back) rakes a skeleton out of a body of water. A witch’s hat bobs on its surface; sinking or rising, we don’t know.

View of “Helping People,” Galerie Lars Friederich, Berlin, 2023

Similarly inscrutable is the eponymous Helping People. Two people crouch forward, embracing in commiseration as the whole, black world behind them erupts in the celebratory glee of nighttime fireworks – streams of bright color pollinate the dark sky, but offer no clue as to what has transpired. The empathy elicited by the weeping figure quickly turns to dark humor: The faceless consoler is a witch wearing the hat from the lake surface of Witch Hunt; the aggrieved, comically enlarged shoes.

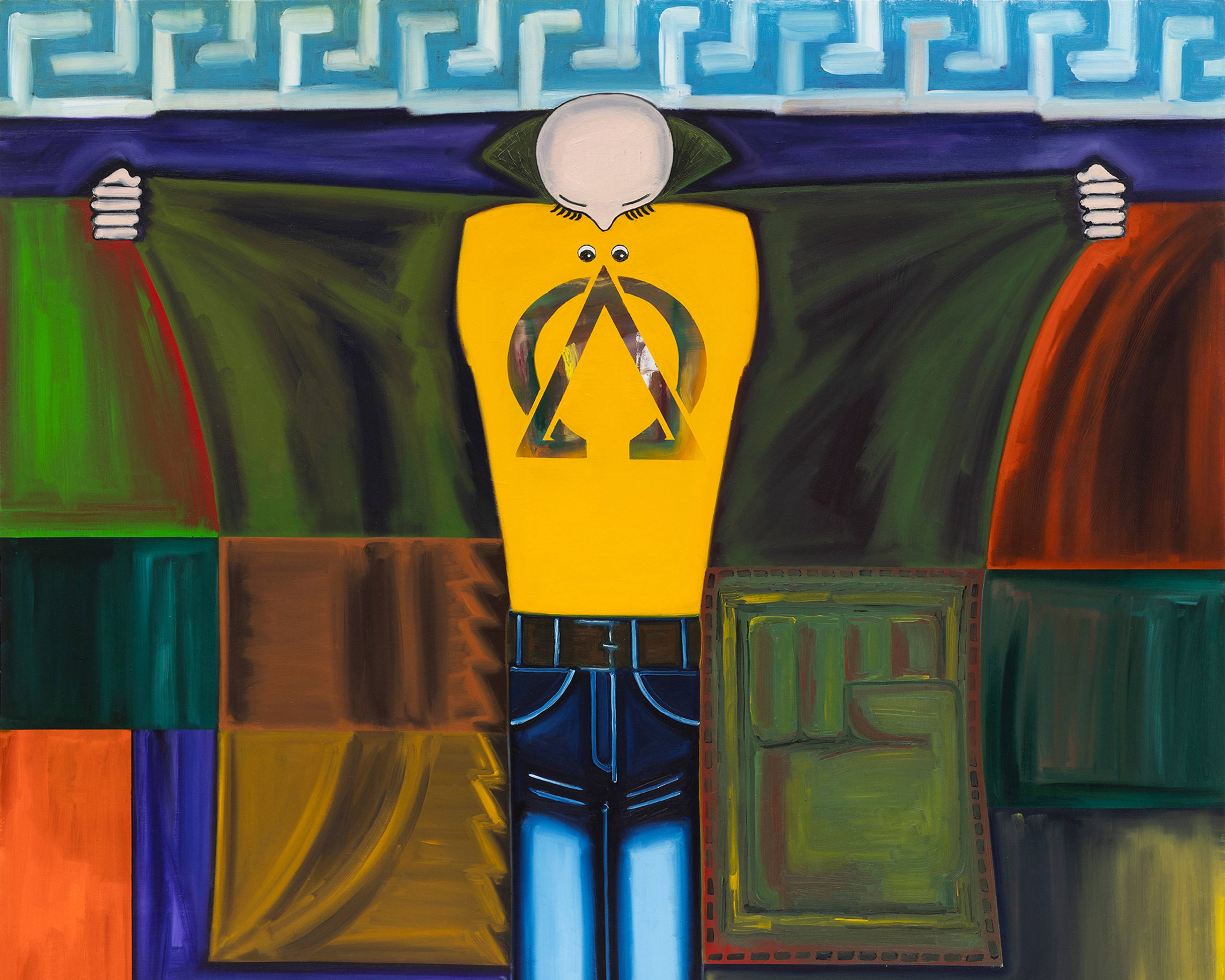

What’s going on here? A clue: the solidarity fist that recurs throughout, such as the quasi-self-portrait, People Who Look Like Me. The fist, this emblem of shared political commitment, with roots in trade unionism and workers’ movements, when painted here by a co-founder of W.A.G.E., an advocacy group for fair artists’ remuneration, is a loaded emblem. Likely, it’s a cipher for the entire question of political commitment as art, or perhaps in spite of it. In “Helping People,” Soskolne attends to whether or not the work of political altruism can ever be squared with – or indeed be a condition of – the often private work of painting. Provided that art-making requires some degree of selfishness, can there be an equivalent selflessness in that very same act? Soskolne wants to pursue these questions to the end, establishing a more or less hermetic codex of acts, signs, and dialectics that point to one possible asymptote of this radical formalism: a painterly ethics of charity, charting such ideas’ likely self-defeat. In the funky Noah’s Ark Hand Chair, we see the fist opened up, turning into an armchair (or, more precisely a “hand chair”), floating on water the way a Deadhead floats on a mental trip to nowhere.

Lise Soskolne, A Witch Hunt, 2023, oil on canvas, 84 x 99 cm

In Soskolne’s concise accompanying text, she clarifies the roundaboutness of these paintings: “I also believe in struggle without virtue, in owing nothing and having nothing to prove.” She disavows the goal of making “good painting,” a statement that allies her with a counter-painterly tradition that’s actually ubiquitous today (compare Nicole Eisenman). Yet, she expresses something novel when she asks about the virtuous struggle that is “helping others,” which is “without question a necessary and righteous pursuit.” Can we ever reconcile artistic production with altruism? Never mind that altruism, a 19th-century neologism with roots in Christian caritas, is perhaps philosophically undecidable, since it’s unclear whether any act can truly be selfless.

Involving a witch, a dominatrix, and the solidarity fist, Soskolne’s quasi-narrative is obscure, an enigma I read as a possible answer in itself to the question of artistic altruism that guides the show. After all, to clearly convey gifts of understanding is to be rewarded for them. Yet (so the logic goes), a painterly address can hardly be selfless, since the painter takes home the return for such legibility. The converse is that withholding meaning is probably involved in (and surely without any guarantees of) real acts of artistic selflessness. But whereas legibility is required of any politics, that same might not be true for a comparable political economy we might derive from art.

Lise Soskolne, Helping People, 2023, oil on canvas, 94 x 107 cm

This is heady stuff. Previous artistic eras had clear models for selflessness, in theory if not always in practice: devotional and religious art, and art explicitly committed to state interests. For most, secularization is clearly a better alternative. Where Soskolne intervenes is in the recognition that what has replaced art as a devotional category is a vague form of neoliberal self-expression in which individuation enters an economy of visibility. Selfishness becomes art’s sine qua non. The longing for a “signature,” for “visibility” and “recognition” that feel predetermined, needy and thirsty for “success,” is what makes so much painting today feel so crass.

Soskolne says as much without saying it, but the situation is clear enough given our dog-eat-dog, huckster times. Soskolne doesn’t promise an answer; then again, if you’re looking to art for easy solutions, you’re looking in the wrong place.

Lise Soskolne, People Who Look Like Me, 2023, oil on canvas, 117 x 80 cm

___

“Helping People”

Galerie Lars Friederich, Berlin

16 Sep – 4 Nov 2023